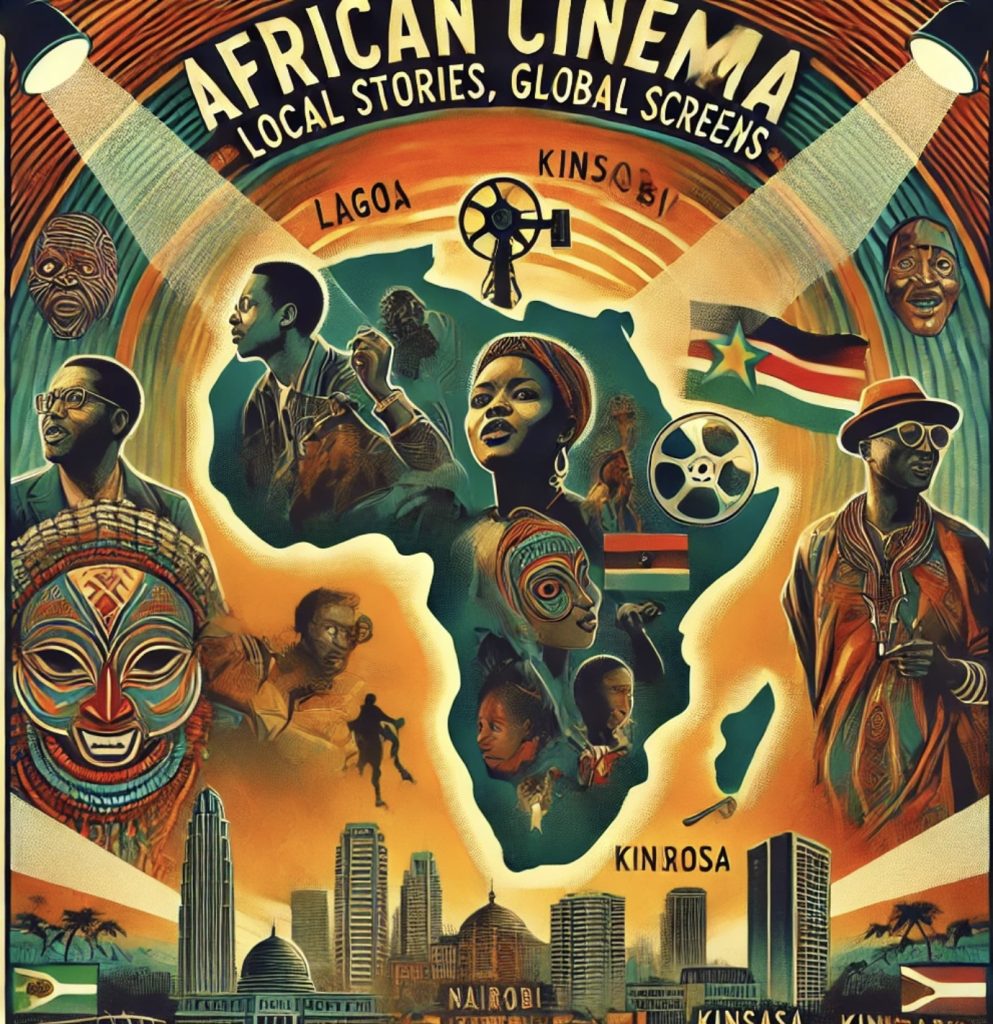

As African cinema strives to transcend its continental boundaries — through its stars, directors, writers, or their works — its success seems to hinge on how authentically it addresses critical local issues. Here, we shed light on this idea through an exploration of three distinctive films.

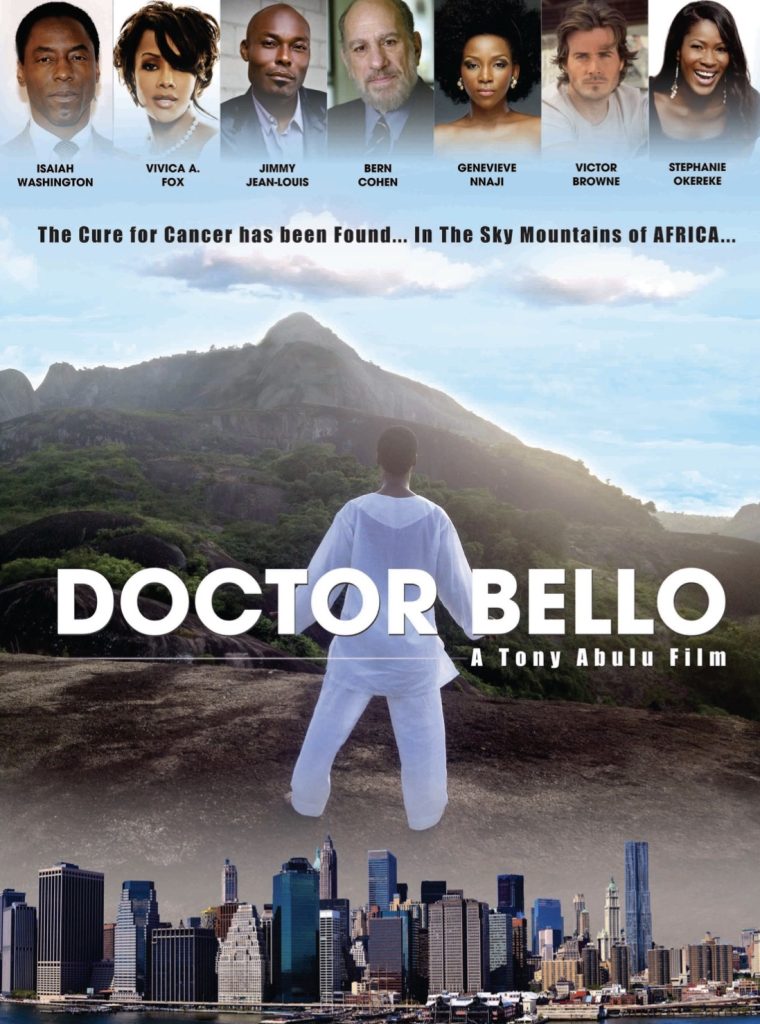

Nollywood, the Nigerian film industry, ranks as the world’s third-largest film producer after Hollywood and Bollywood. Named after Nigeria, this industry recently released a film hailed by both Nigerian and international critics as a timeless masterpiece set to redefine Nigerian cinema’s place on the global map. The film is “Dr. Bello.”

Shot in collaboration with Hollywood, the film features American stars, including Isaiah Washington — known for his role in Grey’s Anatomy — who plays the American doctor Michael Durant. The role of Dr. Bello is portrayed by Haitian-American actor Jimmy Jean-Louis.

Nigerian cinema often relies on modest budgets, with most of its themes revolving around envy, witchcraft, and jealousy — intertwining and contrasting with global cinematic classics.

On the Nigerian side, actress Stephanie Okereke and a host of Nigerian stars contributed to the film. Notably, the Nigerian government helped finance the movie as part of a national effort to uplift the seventh art. A budget of $200 million was allocated to support the cinematic renaissance in Lagos, with Tony Abulu receiving $250,000 as a governmental contribution to introduce the star of the global series Heroes.

The film’s events unfold between New York and Nigeria, narrating the story of the American oncologist Michael Durant, who strives to save a young cancer patient. In his quest, he seeks the help of Dr. Bello, a Nigerian herbalist. However, the police intervene, questioning Dr. Bello’s healing abilities, accusing him of sorcery, and arresting him in New York. As a consequence, Dr. Durant is dismissed from his job.

Developing countries need governmental support across vital and cultural sectors, coupled with their citizens’ efforts to achieve an economic renaissance that will undoubtedly reflect on all aspects of life. This is a path that many countries in Africa have taken, successfully making significant strides.

In a twist of fate, Dr. Bello is diagnosed with cancer while serving his prison sentence. He asks Dr. Michael to travel to Nigeria to fetch an elixir of healing for him.

The film is directed and produced by Tony Abulu, a renowned Nigerian filmmaker who stated that Nigerian films have a vast following in Africa but aspire to reach further and introduce their works to the world. Despite being fully aware of the costs of producing a film of this scale, Abulu insisted on both directing and producing it.

The film’s premiere in Washington was a remarkable success, with critics expressing admiration for its storyline, much like its sensational reception in Lagos, where thousands flocked to attend the first screening.

Nigerian stars have made their way to the global cinema screens, starting with minor roles and eventually becoming prominent figures in Hollywood. Actress Eve Eke is a prime example — an actress, writer, and media personality who, like many of her colleagues, returns to Nigeria, her homeland, now and then to collaborate on joint film projects or support charitable causes.

Some of her fans on Facebook expressed their disappointment, even writing messages on the walls of her house in the Nigerian capital, frustrated by her perceived neglect. In response, the star fired back, saying, “I don’t live in the sky of Facebook. I work on the ground in reality. If I’m not writing replies, I’m sharing my thoughts on my Facebook wall.

Kinshasa Kids Film

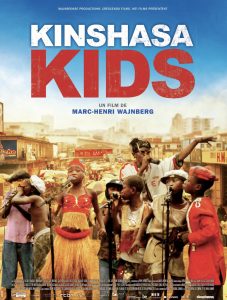

The film follows two parallel paths: one musical and the other social, embodied by the miserable children of Kinshasa. It does not delve much into the wealthy class of society, who view this impoverished segment as a way to grow their fortunes. Instead, the director replaces them with the police force, portrayed as defenders of their interests — despite the fact that a significant portion of the police force itself belongs to this crushed, impoverished class at the bottom of the Congolese social hierarchy.

There are more than 30,000 homeless children in the streets of Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, pursued by the military forces who exploit, hunt, and abuse them. Their misery doesn’t end there; the residents of Kinshasa insist on accusing them of witchcraft, labeling them as “Shégués.”

In a remarkable cinematic experiment by Belgian director Marc-Henri Wajnberg, blending documentary with fiction, the film Kinshasa Kids was born. The director relied on real-life protagonists to tell the story of Emma, a talented boy who dreams of forming a rap music band with the help of his committed musician friend, Bobsan. Through this lens, the film explores the lives of street children and the misery they endure. Perhaps the reason for mixing documentary with fiction was the director’s desire to soften the harshness of reality and cast doubt on the existence of such extreme misery. According to film critics, the movie is “a cinematic work wrapped in the deceit of fiction,” suggesting that the director did not wish to diminish the severity of their suffering but sought to view it from a narrower perspective.

The children of Kinshasa retreat to their musical oasis, playing and composing in beautiful harmony, dreaming that their music might one day reach an audience beyond their makeshift neighborhoods. Their humanity shines in moments of peace and warmth, as they dream of becoming people of value in their own country. The film reveals the depth of their musical heritage, rooted in their authentic African spirits. Music flows through their veins, far from their miserable reality. It becomes their only alternative to the destruction of their souls, allowing them to forget their poverty and harsh reality as they open themselves to spiritual worlds untouched by the brutal harshness of their city.

The film concludes with a scene showing the music band founded by the children themselves. They invite police officers and street residents to listen to their musical creativity. Together, they share in the joy, moving to rhythms drawn from their rich history and heritage.

Wajnberg presents Kinshasa as a city torn to the point of fragmentation between its profound, inherent African cultural heritage and its attempts to catch up with technology — a goal that seems out of reach for a city so harsh to its own people. Music remains one of the most prominent elements of African cultural heritage. The film’s opening scenes depict rituals to exorcise evil spirits from the children’s bodies on the streets of the capital, serving as a powerful introduction that skillfully captures the relationship between the modern and the traditional — between what is new and what is inherently rooted in ancient African culture. This contrast embodies the bitterness of many African nations losing their identities in pursuit of technology, modernity, and progress.

This film was recently screened in Paris during the Francophone Cinema Days. Before that, it was part of the official competition at the Toronto, Venice, and Thessaloniki film festivals — some of the most significant cinematic events in Southeastern Europe. Thanks to this film, some of its young stars were able to escape their miserable reality and return to school after receiving substantial support from various organizations. Additionally, the talent of the film’s lead actress, Rachel, was discovered. She later starred in “Rebelle” (War Witch), the Berlin Award-winning film, which was also shot in Kinshasa.

Nairobi Half Life

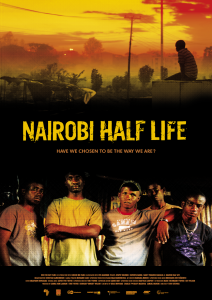

A cultural and intellectual renaissance, perhaps absent from the Arab and global scene, is being experienced by the African continent. This revival manifested cinematically when the Kenyan film “Nairobi Half Life,” directed by David Tosh Gitonga, was officially nominated for the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. The film, which focuses on the world of organized crime and the lives of gangsters in Nairobi, quickly topped the box office in Kenya upon its release.

Sensing this tangible and remarkable African awakening, the management of the Cairo International Film Festival (35th edition) ensured a strong and diverse presence of African cinema this year. The festival featured nine films addressing various issues from the reality of African society, including “Nairobi Half Life”. In addition, a seminar titled “The African Day” was held to discuss the role of African cinema as a medium for political, social, and cultural liberation, as well as its role in presenting Africa in a positive light that reflects its progress and the artistic passion of its people.

The screenplay of the film is a realistic narrative from the new generation of African cinema. It tells the story of those who left their small villages for the big cities, believing they could fulfill their dreams there. This is the journey of the film’s protagonist, Mwas — an ambitious young man who dreams of entering the world of acting. However, on his very first day in Nairobi, his belongings are stolen, forcing him to delve into the world of crime just to survive.

Nairobi Half Life is an attempt to add a human touch to the perpetrators of organized crime in Kenya, seeking to change perceptions or at least soften the impact of these realities on viewers and in everyday life. However, this approach was criticized by film critics, who argued that “crime remains crime, regardless of its causes and motivations,” according to their reports and opinions.

David Tosh Gitonga, the director of the film, who personally experienced the world of crime by spending time with gang members — such as car parts thieves — aimed to portray events truthfully and to deepen his understanding of the culture of crime. He remarked:

“Crime is wrong, no doubt, but have we ever seriously asked ourselves: why does crime happen?”

As for the Kenyan actor Maina Olwenya, one of the film’s stars, he believes that “Nairobi Half Life” represents a turning point in the history of Kenyan cinema. For the first time, there was a large team of producers and actors, along with a wealth of screenplays for a single film. From his perspective, the film serves as a reference and a model for African cinema.