I came across this information about the homeland of A. Hannibal in July 1999, while flying on another business trip to Africa. It was in an article titled “Pouchkine, écrivain russe. Noir, génial et subversif” in a special issue of the journal “Presence africaine,” titled “Pouchkine et le monde noir.” It turned out that Hannibal was born in a country where I had been on a business trip for the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) in May 1985, and precisely in these very places!

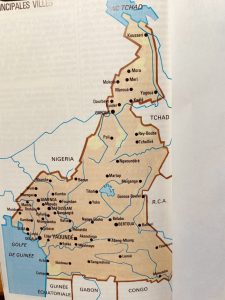

Let me tell you more about it. Our international group, which included experts in cement plant design from Slovakia and France, was tasked with inspecting in Cameroon and Tchad limestone deposits and other raw materials, production and sales conditions, and other issues necessary for preparing feasibility studies for the creation and operation of two cement plants in these countries. I departed Vienna on May 11, 1985, with layovers in Paris, Lome (Togo), and Douala (southern Cameroon), arriving in Yaoundé, the capital of Cameroon, on May 15. The weather in Yaoundé was like that in September in Sochi in south of Russia. I stayed at a nice hotel overlooking the city lake. It was warm, and a cool breeze blew from the lake. After ordering tea, I sat on the veranda and admired the view of the city’s surrounding mountains. Everything was going perfectly.

In the following days, we worked with the director of the UNIDO office in Yaoundé and staff from the Ministry of Industry of Cameroon to prepare a detailed work program for the project and necessary areas to visit in Cameroon and Chad. Before departure, I met with the Soviet ambassador to Cameroon and Chad. His information was completely unexpected for me. He explained that Chad had been at war with Libya for several years, and, in addition, a civil war was ongoing between various factions. The embassy in Chad had been closed for two years, with only guards remaining. They reported that a bomb had hit the embassy’s roof and complained of not receiving salaries. The ambassador asked me to pass by the embassy to see if they were still there. I was unaware of the war and became anxious, anticipating additional difficulties for our mission in Chad.

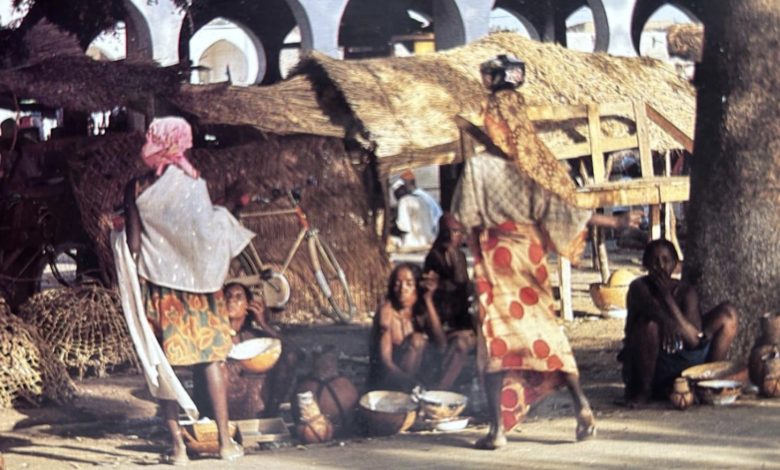

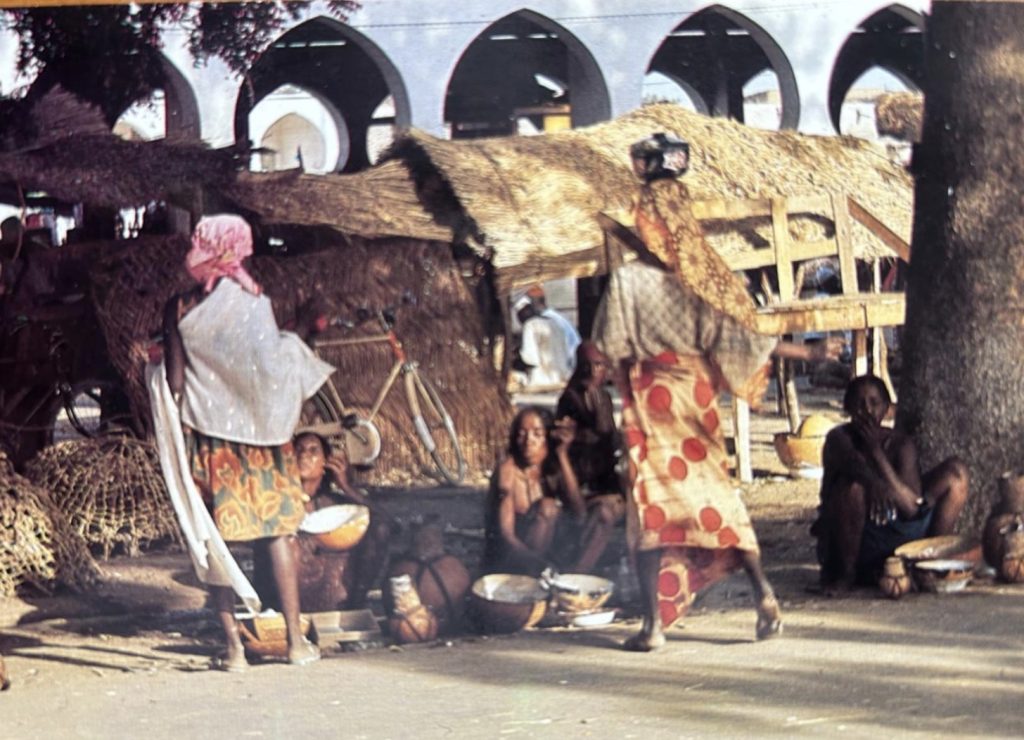

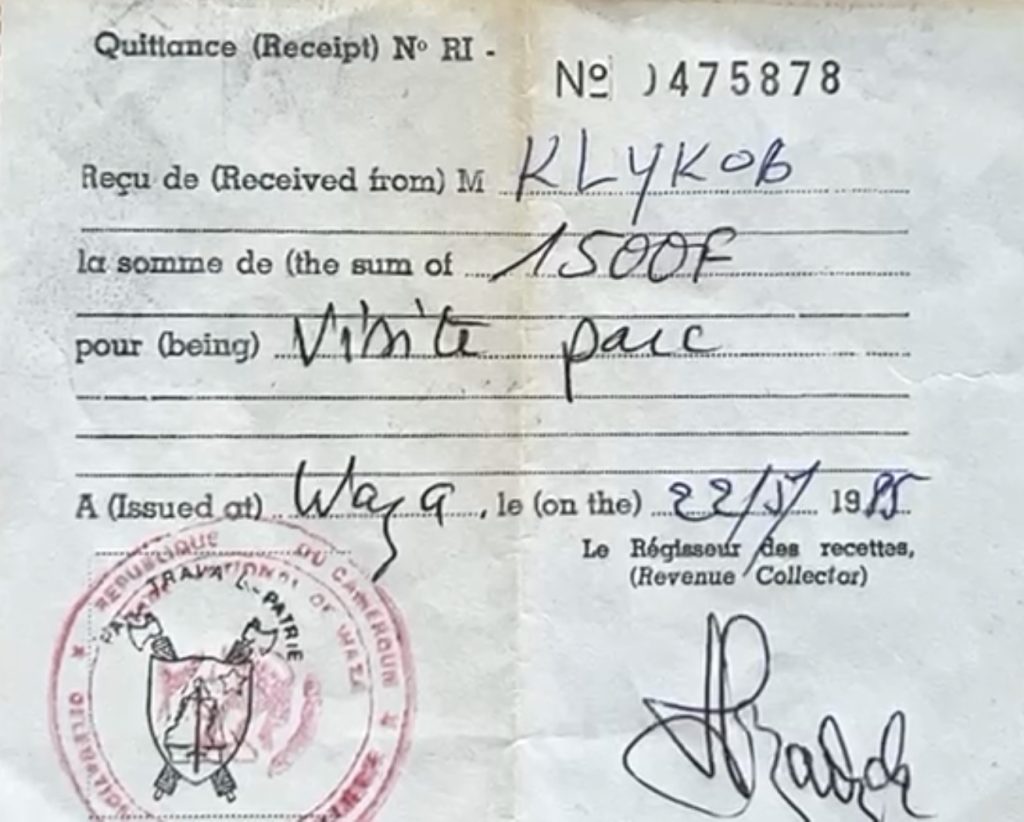

On May 19, we flew to northern Cameroon, to Garoua, where experts awaited us. Over the next six days, traveling in all-terrain vehicles and jeeps with military escorts, we visited promising areas of limestone deposits and potential cement plant sites in Chad (Pala) and Cameroon (Figuiel). On May 22, we traveled from Maroua through the Waza National Park to N’Djamena, the capital of Chad. There, we worked for three days with representatives of Chad’s government and visited Lake Chad. From N’Djamena, I flew back via Paris to Vienna, where I landed on May 27.

This was an interesting but very challenging trip, mainly due to the long journeys by car and the difficult situation in Chad. Overall, we traveled over 1,000 km, often on sandy and dirt roads. In the Chadian savannah, we got stuck in the sand; in the Cameroonian jungle, we were mired in mud on swampy road sections. But I saw things I could never have imagined.

At the border entering Chad, armed soldiers stopped us. We were in a UN-marked car with an escort. While we waited, one of the cars ahead of us in the queue was taken behind the checkpoint. Gunshots followed. We did not see that car again. Our documents were carefully checked, and we were allowed to proceed. On the way to the Pala mineral deposits, two young soldiers armed with rifles accompanied us, occasionally firing into the forest. After five hours on the road, we stopped at a roadside eatery and requested something meaty to eat. They brought plates with a hot dish. From the pieces of meat and garnish on my plate protruded a leg with fur on the end. I asked, “What is this?” It turned out to be a cat! I asked if there was any other meat, and they replied, “No.” I had to eat it.

That same day, without an escort, we returned to Cameroon to Figuiel, where we visited a cement plant. Then we traveled north, spent the night in Maroua, and the next morning set off for N’Djamena, Chad’s capital. On the jungle road near the Waza National Park, our local driver suddenly stopped and invited us to get out. We followed him and, just five meters off the road, saw small huts about a meter high. From the noise, a man and a woman, not more than a meter tall, emerged with a baby. They were pygmies. They greeted us with cheerful smiles, and we smiled back. It was so unexpected and fascinating to meet such people for the first time. They had always lived here. Even after a road was built through the jungle to the village where the country’s president was born, they remained in this place.

Half an hour later, the road approached a river in the jungle. The driver said that on the other side was a protected area of the national park designated by UNESCO as a natural habitat for gorillas. Suddenly, he suggested me go into the forested thickets to try my luck at seeing gorillas. I agreed, and we crossed the river in an old boat. In the swampy river water, snakes swam, and horseflies buzzed around us while the sun blazed overhead. The driver explained that in the forest, I should press my back against a tree and avoid moving. He handed me an old rifle in case a gorilla noticed me. Sweating profusely, my back drenched in fear, I flinched at every sound. Only later did I learn that gorillas are so fast that I wouldn’t have had time to react before being torn to shreds. Fortunately, no gorillas appeared.

We continued our journey safely. The next morning, I discovered that my back, from where I had been sitting to my shoulders, was covered in blisters from horsefly bites. Late at night, in the darkness of the forest road, our car was stopped by a man offering to sell a skinned animal carcass. A Frenchman traveling with us recognized it as a porcupine, whose meat he enjoyed, and bought it. Unfortunately, I didn’t get to try the porcupine, as he stayed in Cameroon while I continued on to N’Djamena. Looking at the map now, I realize that I had passed just a few kilometers from Logone-Birni, the homeland of A. Hannibal. N’Djamena, capital of Chad at the time, left a heavy impression on me. The city was semi-ruined by the war with Libya, ongoing since 1978. In the hotel where I stayed, there were almost no guests. The air conditioner was broken, the vent banged against the pipe when turned on, and the pool was empty. Life was recovering very slowly. Thanks God, the national project director in Chad was present. We summarized our expedition’s results with him, and I invited him to continue working with UNIDO in Vienna. Returning to the hotel, I asked the driver to pass by our embassy. Reluctantly, he agreed, on the condition that I not show myself in the window. I saw the building with a collapsed roof and a yard where a family with small children sat by a fire. I asked one of my Cameroonian travel companions to report this to our embassy.

Lake Chad

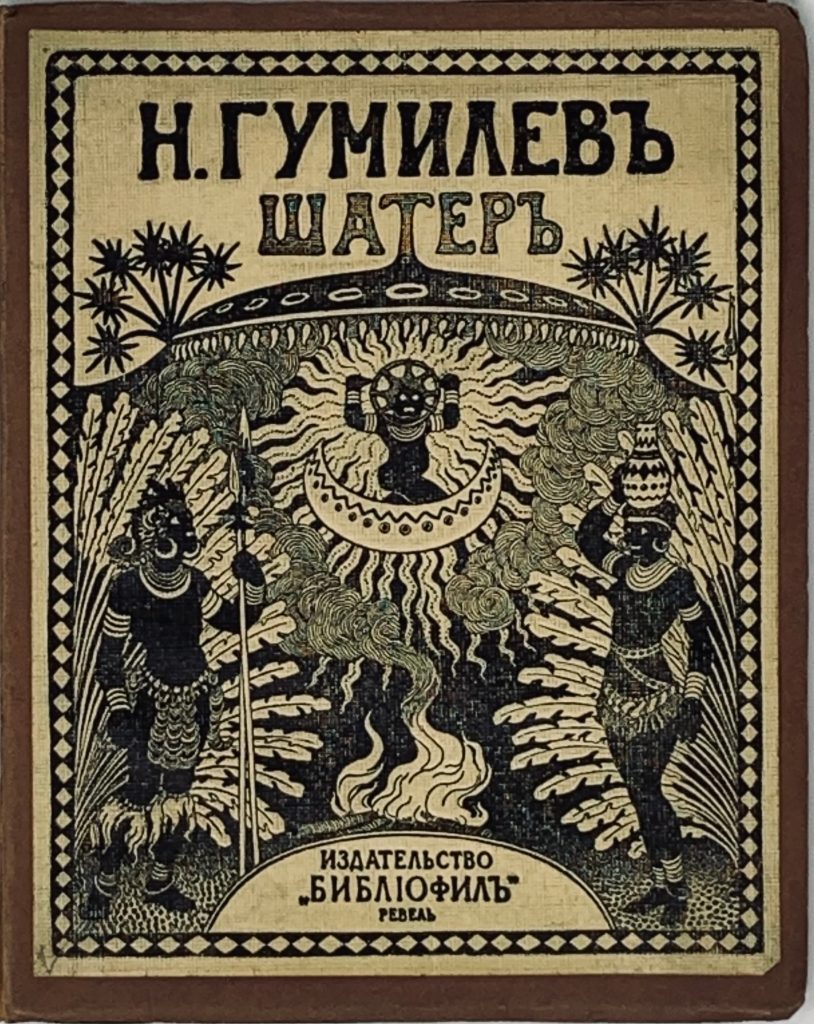

I had a strong desire to see Lake Chad, which was nearby. For me, Lake Chad was romanticized by Nikolai Gumilev’s poems “The Giraffe” and “Lake Chad,” written after his visit here in the early 20th century. I loved these poems. One evening, we went to the lake. It was a dark night with a full moon. We lit a fire and waited. But… no giraffes and almost no romance. It was deserted and quiet. I must say that during my entire stay in Chad, I did not see a single live giraffe. However, passing by a souvenir shop in N’Djamena, I saw magnificent bronze giraffes in the window. I had already packed my luggage and could only buy a small one. A month later, my friend, the national project director, brought me two large bronze giraffes to Vienna. Now they are in my apartment, and looking at them, I remember Chad and my journey there and to Cameroon. Later, I wrote a poem dedicated to N. Gumilev and his poems about Lake Chad.

On Lake Chad

“Listen: far, far away, on Lake Chad,

A giraffe, so refined, gently roams…”

— N. Gumilyov, “The Giraffe”

One day, on a flight for affairs,

I found myself near Lake Chad,

Where in Gumilyov’s verses,

A refined giraffe once had trod.

Alas, no giraffes now wander that land,

Where young men with rifles, in morning’s gray hue,

Shoot at their own yesterday, high on the sand,

In savannas on jeeps, as if filming a view.

No more on the waters of Chad, Lake Chad,

Is the romance of Africa, or gentle giraffes.

Only endless war, and its sorrowful pad,

Brings grief to its people—and us in its grasp.

Bronze giraffes now stand on my table,

A gift from a friend on a memorable day.

He brought them from N’Djamena to Vienna:

Two giraffes in a bag as he made his way.

The lake was also famous for another reason. In 1969 the renowned traveler and scientist Thor Heyerdahl (a Norwegian anthropologist, scientist, and explorer), with locals from the Lake Chad region, along with specialists, built the first papyrus boat “RA”. On it, an international team, including the Russian doctor Yuri Senkevich, traveled 5,000 km across the Atlantic Ocean from the shores of Africa to near America in 56 days, stopping just a few hundred meters short of the continent. Despite the difficulties of my expedition, I was pleased with the achieved results. We fully accomplished our mission, and I learned much about the history and lives of the people in those countries and their astonishing—especially for a northerner—natural environment. It’s just a pity that at that time I didn’t know that Logan-Birni was the real birthplace of Hannibal!

The Past, Present and Future of Logone-Birni city

Only later did I learn that Logone-Birni city is the true homeland of Hannibal. In 1987, I purchased a French-language book by A. Debel titled “Cameroun aujourd’hui.” It mentioned the city of Logone-Birni: “At its peak, the city had 150,000 inhabitants. Today, it is ten times fewer. At the end of the last century (the 19th century), the king of Logone-Birni, unwilling to pay tribute to his neighbors, decided to attack them and called for the help of a famous military leader named Rabah from the Nile Valley. However, instead of assisting, Rabah overthrew the king of Logone. In 1900, he himself was defeated by French colonial troops. Nowadays, this city is slowly dying. Many homes are abandoned by residents, crumbling, and disappearing. Even the fortifications of the sultan’s palace have turned into ruins, despite the fact that the sultan himself still resides there.” (A. Debel “le cameroun aujourdhui,” les editions du jaguar 1986, (4th edition), .159, logone-birnii).

Today according to my Cameroonian friend Jean-Alain Ngaput, a doctor of philology, slavicist, and representative of the International Russophile Movement (IRM), established in 2023, the discovery by D. Gnammankou that Hannibal, the ancestor of Alexander Pushkin, was born in Logone-Birni has brought worldwide attention to the city. The city and sultanate of Logone have been revitalized. Recently, the Sultan of Logone appointed D. Gnam-mankou as a judge in the Sultanate (the third most important position). He will oversee international cooperation.

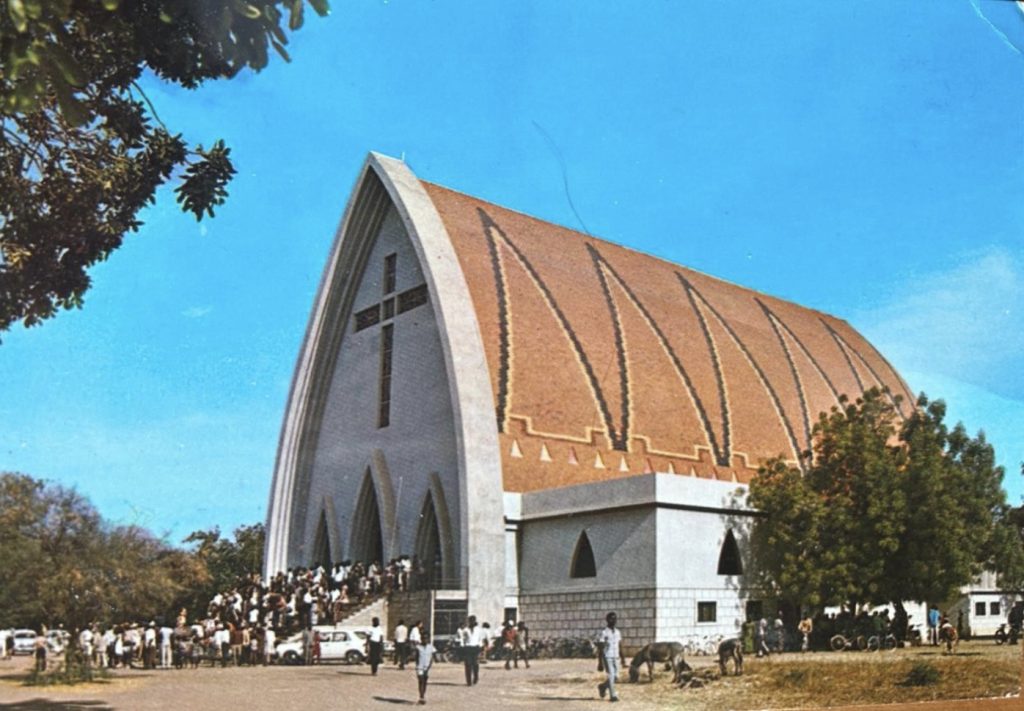

Interest in the Logone province and Logone-Birni has grown not only among the government of Cameroon but also in the international cultural community. In recent years, international conferences dedicated to A. P. Hannibal and A. S. Pushkin have been held there. In 2021, I was invited to such a conference, but unfortunately, I could not attend due to COVID.

At the Russia-Africa summit in St. Petersburg in July 2023, a decision was made to erect a monument to A. S. Pushkin in Cameroon. This initiative was supported at the founding congress of the International Russophile Movement (IRM), created at the same time. Preparations for the Pushkin monument in Cameroon were included in the IRM’s upcoming events. The project is funded by the “Russian World” Foundation. In Cameroon, it is spearheaded by Jean-Alain Ngaput as the IRM chairman in the country.

This is wonderful news for all admirers of the two geniuses, A. P. Hannibal and A. S. Pushkin. As a citizen of the country where the great Russian writer Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin was born and created, I would like, on behalf of all Russians, to thank the leaders of Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Cameroon, who have done much and continue to do so to popularize his name and works in their countries, and to celebrate their achievements. A. S. Pushkin and his works belong to everyone. Even 225 years after his birth, his popularity has truly become global!

VK translation of 22.01.2025