This book is far from being a garland of academic exercise or a festschrift; it’sa testament to a life lived deliberately without borders, to the healing power of art, a blueprint for interdisciplinary dialogue, and a literary microscope that examines illness, not just of the body, but of our society.

Dr. Okediran has refused to be boxed in, living without the limitations that confine many. A physician who writes like a poet, a legislator who dreams like a novelist, and a writer who dares to heal the soul of a nation. He’s a physician with a keen diagnostic eye, not just for individual ailments, but for the fevers and fractures within our society. He’sawriter, wielding his pen like a scalpel, dissecting complex issues with clarity and courage. He’s the politician who stepped into the chambers of power, not as a tourist, but as a participant-observer. And he’s the literary administrator, building bridges and nurturing the next generation.

This collection captures that unique synergy, mapping how Dr. Okediran seamlessly blends the clinician’s empathy with the writer’s narrative power. He doesn’tjust describe social injustice or ill health; he diagnoses its root causes, explores its human impact, and implicitly, sometimes explicitly, prescribes pathways towards healing for both individuals and society.

Professor Falola rightly highlights Dr. Okediran’s role in bridging the often-artificial gap between the sciences and the humanities. From my perspective as an activist, this is crucial. We often see policy detached from human reality, or passion lacking practical grounding. Dr. Okediran demonstrates how deep knowledge of human biology and suffering, rooted in medicine, can powerfully inform our understanding of social structures and the need for justice through literature and politics.

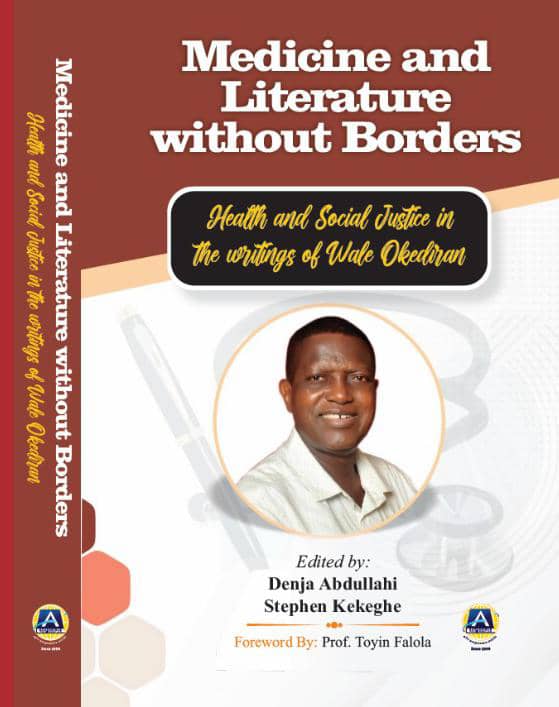

I must acknowledge that the editors have done a masterful job in bringing together the deep reflections of diverse voices—critics, scholars, writers, and admirers from across the continent and beyond. It traverses beyond Part I, focusing on critical Essays with 15 chapters, Part II of five chapters collected as Reviews, the interviews with two chapters serving as Part III, and Part four collating the tributes with 15 chapters. Each is a unique prism through which we view the work and mind of Dr. Okediran, as contained in the 359 pages of 37 chapters.

“I kneel before you, healer… I am the city searching for lights.”

The opening words of Professor Toyin Falola’s foreword are a bold invocation, not of a man who fixes symptoms, but of one who sees the story behind the sickness, the soul behind the statistics. This is the ethos that defines both this book and its subject.

The very title, Medicine and Literature Without Borders, is not metaphorical. It is a literal call to tear down the walls between disciplines, to see how science and story, diagnosis and dialogue, can work hand in hand to treat the disease of our societies.

Each chapter of Part One – Critical Essay examines Dr. Okediran’s novels and stories through various critical lenses. What strikes me, reading as someone engaged in social change, is the recurring focus on justice—whether it’s medical ethics, the trauma of conflict, political corruption, gender violence, systemic inequality, mental health, or the quiet resilience of everyday people. These essays confirm that Dr’s work consistently grapples with the power dynamics that shape, and often break, human lives. Outstanding is “The Physician as Writer,” which lays the foundation for understanding Dr. Okediran’s narrative craft. He reminds us that the physician and the writer are both social witnesses – one diagnoses the body; the other, the soul. We see this dual lens vividly in Rainbows Are for Lovers, Storms of Passion, and Madagali, where the hospital becomes a theater of justice and love, and illness, a metaphor for social dysfunction.

Further on Chapter four, “Stethoscope on a Diseased Society,” dissects terrorism and trauma, the ripple effects of insurgency in Madagali as a literary autopsy of Nigeria itself, exposing how conflict seeps into the sinews of health systems and the human psyche. It is literature as a prognosis, warning, and balm. Showing how literature functions as both X-ray and scalpel, revealing and confronting what lies beneath. In Dr. Okediran’s hands, terrorism is not just a security issue, it is a public health crisis. Trauma becomes generational. Hospitals collapse not only from lack of funding, but from moral fatigue. In Madagali, the wounds are not just physical; they are civic, psychological, and spiritual.

What emerges is the portrait of a man who has not only written the human condition but lived it deeply: as a physician with compassion, a lawmaker with integrity, and a writer with unwavering commitment to justice.

Dr. Okediran’s tenure as a Member of the House of Representatives is not just background—it is raw material. His novel Tenants of the House, and the chapters that analyze it, offer rare insight into Nigeria’s political theater—its paradoxes, rituals, and ethical hemorrhaging. The exploration of Tenants of the House is particularly resonant for anyone who has observed Nigerian politics closely and its never-ending “fiesta of dramas.”

One particularly striking analysis links the Abiku/Ogbanje motif to political allegiances, revealing a cycle of “born-to-die” governance, where promises are stillborn, and loyalties are mystical, not moral.

Here again, literature becomes a lens of diagnosis and a site of accountability. We do not only ask what is wrong, but also how can we imagine something better?

And then we come to the bold, complex terrain of Haruna Adaji and co, whose essay on Madagali ventures into posthumanism, examining how war, data, migration, and capitalism reshape our very sense of identity.

They show how, in Okediran’s work, the body is no longer a fixed site – it is vulnerable, hacked, and displaced. These are not just literary experiments. They echo our digital anxieties, refugee crises, and fractured psyches.

In this way, Dr. Okediran not only reflects contemporary reality, but he also anticipates it. He warns, imagines, and stretches the literary form to hold the complexity of our modern condition.

Once again, quoting Professor Toyin Falola;

“I kneel before you, healer… Iam the boy finding his purpose. Iam a city searching

for lights. ”

These are not just poetic lines. They are our collective refrain. They remind us that literature, like medicine, must first do no harm and then heal. Therefore, justice begins with empathy, and empathy begins with a story.

Part II – Reviews, with five chapters, offers sharper focuses, particularly on more recent works and his travel writing. They provide accessible entry points and contemporary reactions, highlighting Dr’s ongoing and urgent engagement with Nigeria’s issues. This section adds texture, reflecting on specific works like Tales of a Troubadour and others, reveals how Dr’s narratives traverse genre and geography, romance in wartime, love in chaos, and hope in uncertainty. They read like a public policy lecture disguised as literary criticism, and I say that as a compliment. Because, in truth, our national discourse is impoverished when it ignores what our writers are already saying.

Then come the “Interviews,” where we get closer to the source, hearing Dr. Okediran in his own words as both subject and storyteller. His characters grapple with asthma, depression, betrayal, and systemic failure, often drawing from real patient encounters, refracted through imagination.

In “Literature, Medicine and Politics Are My Wives,” he reflects with humility and insight on the balancing act between his professions. As captured by Phateema Salihu, it reinforces the authenticity we see in his writing. It’s the voice of someone who has seen things, both in the clinic and in the corridors of power and feels compelled to speak. We are reminded that behind every diagnosis is a story, behind every medical file is a life, and that Dr. Okediran, with both stethoscope and pen, treats both.

And finally, the “Tributes” are a moving chorus. For an activist, this section speaks volumes about impact. It’s one thing to write powerfully; it’s another to translate that into tangible action. The tributes from fellow writers, administrators, mentees, and international figures are not just encomiums, they are evidence. They speak of his administrative skill, his generosity, his commitment to building institutions like the vital Ebedi International Writers Residency – a concrete investment in the future voices of Africa, documented here by those who have directly benefited. This, for me, is where the ‘people’s voice’ aspect truly resonates – it’s about creating platforms and empowering others, and this is where I call Dr. Okediran a literary gardener, cultivating voices across Africa.

No review of this book would be complete without acknowledging its feminist engagements. The essay on After the Flood confronts medical ethics and social justice, asking: who gets to live, to heal, to hope, when the system is broken? The chapter on “Drowning in Silence, Rising in Defiance” examines how women’s trauma is misdiagnosed and mishandled by systems, tradition, and silence itself. Even more piercing is the feminist reading of A Visitor for Grandma, Bintu shines a light on gender- based violence and dementia, drawing attention to the often-silenced experiences of older Nigerian women. Raising issues, we rarely discuss ageism, gendered caregiving, and the invisibility of the elderly in public health narratives.

We see characters betrayed by medical institutions and their families, and yet, we also see resistance, reinvention, and resilience. Literature here is both a lament and a rallying cry.

As someone who has spent much of my career advocating for inclusive policy, these chapters reaffirm that storytelling is a form of justice work. Literature is not a luxury, it is a mirror, a manual, and sometimes, a megaphone.

So, what does this synthesis achieve? Medicine and Literature Without Borders firmly establishes Dr. Okediran not just as a crucial social commentator but as a social healer. He writes stories that often go unheard. He asks the questions our systems are too silent to pose. He holds the stethoscope not just to the chest, but to the conscience.He uses his narratives to bear witness, to challenge complacency, and to offer visions of a more equitable and humane society. His ‘physician-writer’ identity isn’t just a biographical detail; it’s the core of his methodology – observing, diagnosing honestly, and writing with the intention to effect change.

This book is essential reading. For academics, it offers rich material for literary and cultural analysis. For medical professionals, it’s a powerful reminder of the human stories behind the symptoms and the social determinants of health. For activists and policymakers, it provides nuanced insights into the Nigerian condition. And for all of us who believe in the power of stories to shape our world, it offers inspiration and reaffirms the vital role of the engaged artist in society.

Across all these essays, one thing is clear: Dr. Okediran’s language is lucid, compassionate, and unpretentious. He does not write over the heads of his audience. His work is accessible to students, deeply layered for scholars, and emotionally resonant for general readers.He writes like someone who still believes that stories can heal. And indeed, they do.The words, from Professor Falola’s foreword, are prophetic. In them, we find not just an individual plea, but the voice of a continent, and perhaps even the collective cry of a world in disarray. Because at the heart of every nation—whether in Ibadan, Accra, Cairo, or Cape Town—there is a boy still searching for purpose, a girl still longing for freedom, a city still fumbling toward the light.

And so I ask us, here in this literary sanctuary:

What does healing mean today, for Africa, and for the world?

Is it found only in policy and prescription? Or also in poetry, in protest, in story? In how we choose to remember, to speak, to write, to imagine?

Can we, as writers, readers, advocates, and citizens, be healers in our own way?

Can we hold up the stethoscope not just to the body, but to our failing systems, our fractured communities, and our exhausted spirits?This is the challenge that Dr. Okediran’s work lays at our feet—not only to tell stories, but to transform through them.

I wholeheartedly recommend Medicine and Literature Without Borders to everyone present and beyond.Having known Dr. Okediran for a decade not in a hospital ward or literary salon, but in a space where advocacy met artistry, what struck me then, and continues to intrigue me, is his quiet fire—a gentleness that contains great depth, a clarity of purpose that speaks softly but acts boldly. Thus, this book is a true reflection of the man – dedicated, multifaceted, deeply humane, and always striving to connect, to understand, and to heal. This collection is more than a celebration of 70 years; it’s an exploration of a legacy that continues to unfold and enrich us all.

He is a man who wears many hats and balances many hearts: a medical doctor by training, a legislator by service, and a writer by calling. But above all, he is a healer of the body, of the nation’s conscience, and the African spirit.In the Yoruba culture, 70 is not just a number. It is an age of honor. It is the age of the elder’s voice, it is the orí that holds the weight of wisdom. In the life of Dr. Okediran, we see not just 70 years of living, but of giving to country, to community, to creativity.

To you, Dr. Wale Okediran—Happy 70th Birthday.

You have not only lived a life of purpose; you have inspired us to do the same. May your pen never dry.

May your stethoscope always find the truth.

And may your journey continue to remind us that healing—true healing—requires both science and story.

Heartfelt congratulations, sir, and profound thanks to the editors and contributors for this invaluable work.

Thank you, and God bless you all.

April 19, 2025

arotimi@caaid.org