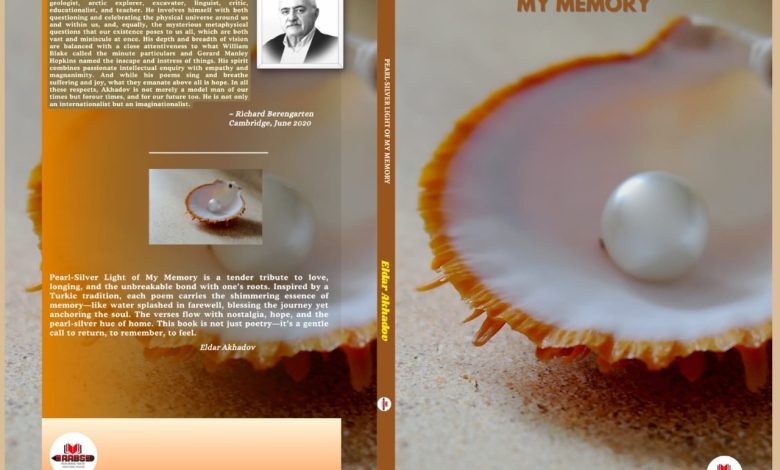

Eldar Akhadov’s Pearl-Silver Light of My Memory (Aabs Publishing House, 2025) is an expansive and genre-defying poetry collection that merges philosophical parables, lyrical confessions, whimsical tales, and heartfelt reflections. The volume reveals a poet who is deeply rooted in his cultural and geographical past, yet unafraid to reach into the surreal, the sensual, and the sacred.

Akhadov—a prolific author with over one hundred books in multiple languages and a recipient of prestigious international literary awards—brings together diverse forms and voices. This collection, organized in several parts, reads as both a spiritual autobiography and an invitation to journey through the recesses of human emotion and imagination.

The first section, “Fairy Tales,” is a series of micro-stories, parables, and fantastical metaphors rendered in minimalist prose-poetic form. Akhadov’s use of anthropomorphic characters—wolves, squirrels, clouds, and clowns—revives the moral economy of fables but with modern existential undertones. In “A Tree of Happiness,” a man sues his sadness, only to realize its potential for joy when it blooms into a tree: “Once the sadness saw the flowers, it stood dumb with astonishment and fully blossomed. There’s no sadness anymore, but there’s a tree of happiness” (15).

The piece “About Mercy” is especially poignant, where Captain Hook, no longer a villain, pleads for a second chance: “Don’t make former Captain Hook out of me. I’m not him. I’m not that kind of person anymore!” (20). These tales critique contemporary lack of empathy while preserving the childlike cadence of folklore.

In the “Poems” section, Akhadov turns toward love in all its intensity—physical, emotional, and spiritual. His language is unabashedly sensual and often ecstatic. In one early poem, he writes: “A trickle of honey on your chest did slide, / A small drop on your lips was sparkling” (“Untitled Poem,” 43).

His metaphors are rich with corporeality, yet they soar with mystical longing: “Do scream, do bite, do show me the bliss. / But look again a virgin in the morning” (“Untitled Poem,” 43).

These poems are unabashedly romantic, often recalling the lyrical voice of a troubadour, intoxicated by desire but tempered by tenderness.

The poet’s wisdom deepens in “No,” a striking political poem that explores the difficulty of dissent in a world eager for conformity: “Know how to say ‘NO’ / Even when it’s really scary and there’s nowhere to hide” (48). Here, Akhadov echoes the existential courage of poets like Akhmatova and Mandelstam. He defends personal dignity as “the most precious thing we have” (48). This is poetry not just of feeling, but of resistance—personal, ethical, and political.

In “God Loves Poets,” he recounts his own near-death experiences: from being shot at fifteen to suffering a stroke and open-heart surgery. And yet, he declares, “To fly, I don’t need legs, I need wings. / I’m a poet, I have wings!” (50).

Akhadov’s voice emerges as one that affirms life in the face of suffering and mortality—a theme that unites the varied modes of the collection.

One of the most unexpected and moving sections is “Look into My Eyes,” a deeply confessional epistolary sequence between Nina and Misha. This prose-poetic correspondence chronicles an intense, illicit love affair. At one point, Nina confesses: “What I need is LOVE. Real love. Incredibly huge love… If I don’t have such love, I will have nothing. I will be nobody” (61).

These letters, alternating between erotic passion and spiritual despair, culminate in separation. Nina joins a convent; Misha marries someone else. The section concludes with a direct citation from Apostle Paul: “And now these three remain: faith, hope and love; but the greatest of these is love” (83).

This Christian conclusion recasts their romance as a redemptive passage, a purification through suffering, reminiscent of Dostoevskian spiritual arcs.

In “Baku – Zurbagan,” Akhadov returns to his homeland and its storied histories. His evocation of Baku’s mists and stones is both historical and mythopoeic: “The night city lights shimmer through it, creating an utterly magical aura of a fantastical, surreal world” (88).

He intertwines the biography of Russian writer Alexander Grin with etymological studies of Turkic toponyms, creating a layered meditation on memory, identity, and place.

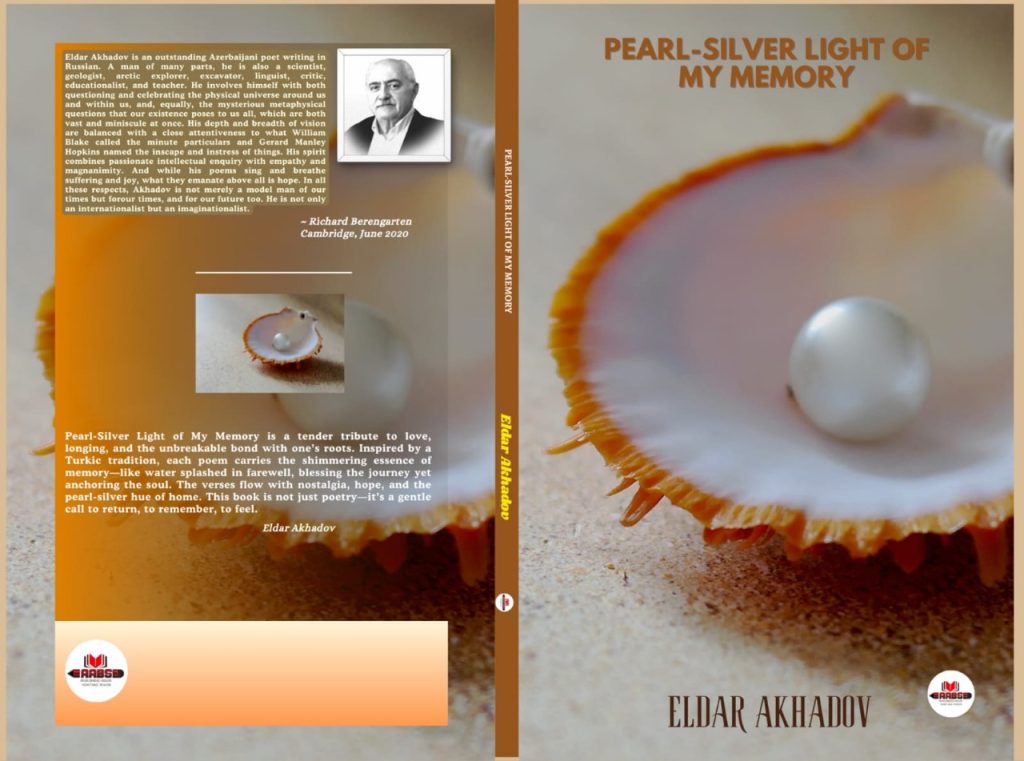

Pearl-Silver Light of My Memory is a luminous, emotionally expansive, and culturally rooted work. Akhadov demonstrates that poetry can be simultaneously intimate and mythic, political and playful, romantic and tragic. Through dreamlike fables, rapturous love songs, and poignant elegies, he draws a map of the human heart and soul that spans continents and centuries.

The book is not merely a collection of poems; it is an invitation into a rich and multi-dimensional world—one in which the “tree outside the window keeps waiting” (46), and where, even in the end, love “never fails” (83).