Imagine a warm, quiet evening in old Edo. The air is still, smelling of charcoal, dried herbs and something sweet – either sake or other people’s secrets. Somewhere in the distance, you can hear the sound of the shamisen, laughter in a teahouse, the clatter of wooden sandals on stone. It is there—to this colourful, vibrant 17th-century Japan—that Ihara Saikaku’s collection Under the Cherry Blossoms transports you.

That’s how I came across Mr. Saikaku’s collection – a book that left me with not just a pleasant aftertaste, but a desire to read more by the author. I think the best proof of this is that I already have five more of his works on my bookshelf (and I’m writing this review almost 10 years after reading it).

It’s funny how the world works: when you see someone every day, you get used to them over time and inevitably start to like them. Before moving on to the stories in this collection, I would like to dwell a little on the author himself. Especially since the first pages of the book are devoted to Saikaku himself — his personality, writing styles, and the themes that interested him.

Therefore, I will allow myself a small lyrical digression — I think it is important to first talk about the writer himself, whose voice resonates throughout the collection. Well, Ihara Saikaku (1642–1693) was one of the most prominent innovators in 17th-century Japanese literature. He began as a poet and once wrote 1,600 verses in a single day, which means that each verse took him, on average, just over a minute.

He later not only broke his own record, reaching four thousand, but also amazed everyone at a poetry competition by composing twenty-three thousand verses in a single day, leaving the scribes bewildered as they struggled to keep up with transcribing his poems onto paper. Impressive, wouldn’t you agree?

However, he gained real fame thanks to his prose, especially the genre of ‘tales of the floating world’ (Japanese: 浮世物語). He wrote about merchants, geisha, courtesans and ordinary townspeople with remarkable candour – without judgement or idealisation, capturing the colourful and contradictory everyday lives of people living in a world full of new temptations, freedom and change. It is also interesting to note that Saikaku is not his real name, but a pseudonym meaning ‘Crane Flying West.’

This image conveys lightness, wisdom, and a sense of impending sunset, as if the author himself were observing the fleeting world from above, trying to capture and convey everything he could. His style is lively, ironic, and rapid, as if he were really writing on the fly, capturing the fleeting, elusive present. Saikaku’s work is the fruit of his individual artistic style and individual artistic consciousness. Reading his work, one gets the feeling that Ihara Saikaku travelled all over Japan, listening to stories, writing them down, observing.

Each story is as if told in a teahouse over a cup of sake: with irony, with mystery, with an inevitable denouement. And indeed, every village has some interesting story to tell. The structure of all his books is particularly pleasing: in most stories (whether at the beginning or the end), folk wisdom is heard: ‘It has long been said…’, ‘Have you heard…’

These proverbs create a sense of living tradition, as if the reader is sitting at a table with the storyteller, who conveys not just stories, but an entire culture of perception of the world. Then a rich plot unfolds. It has long been said that ‘kindred spirits are drawn to each other.’ It’s good when this happens on the basis of goodness, but more often than not, the opposite is true.

Yes, that’s the way it is in this world: if a person has money, everyone considers him witty and refined. And in the ‘merry quarter,’ it’s no wonder to become famous with money. Although this is an old truth, how can we not say: ‘Money decides everything in our world!’ And yet, it is not for nothing that they say: ‘Seventy-five times you will get away with it, but on the seventy-sixth time you will be caught!’ Sooner or later, any deception is discovered.

It was especially interesting to read the stories where there are court proceedings and the mayor makes the decisions. This gives the works additional historical colour, as they reflect real incidents and legal traditions of medieval Japan. This is particularly close to my heart, as my legal studies have had an impact. I also took an interest in medieval Japanese law at one time.

For this, I give the author extra credit. Saikaku’s style can be described as straightforward and concise – without unnecessary metaphors and embellishments, but at the same time very expressive. He writes for townspeople who want to see themselves and their acquaintances in his stories – living, real people, not idealised images. And despite its rather romantic title, Under the Cherry Blossoms is actually a collection of diverse stories from 10 different collections, united only by the author’s perspective and the spirit of the times. I will take the liberty of not delving further into the plot of the stories.

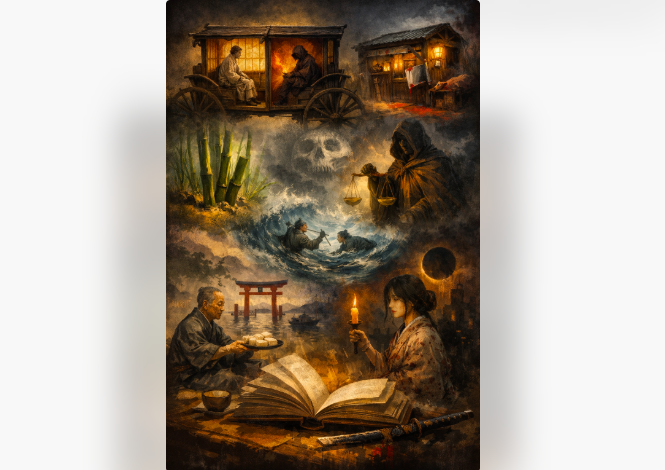

I will only mention those that touched my soul the most: ‘Good and evil do not travel long in the same carriage.’ Separate stories from the collection ‘The Roadside Slaughterhouse’ ‘Trouble sprouting from bamboo’ ‘Death on the waves makes everyone equal’ ‘How choice determined the truth’ ‘The society of one momme’ ‘Rice Cakes in Nagasaki’ ‘The World Plunged into Darkness’ and so on.

Note the conciseness of the titles. ‘Under the Cherry Blossoms’ is not just a collection of stories from the Edo period. It is a window into another world — but not a foreign world, rather a surprisingly familiar one. Even centuries later, everything in these stories still sounds acute. Ihara Saikaku himself is a true writer-observer with an ironic but very warm view of people.

He knows how to see the depth and drama in everyday life and present it with a slight smile and a slightly ironic tone. His characters are vivid, with their weaknesses and passions, familiar and understandable to us despite the distance in time. This book leaves you with the feeling of a real dialogue with the past, where each story is a little lesson and a reason to reflect.

My acquaintance with Saikaku will definitely continue, as will my acquaintance with Japanese literature in general. Human hearts are as different from each other as flowers on different trees. Even in the blossoming capital, everyone lives their own way, and in the remote provinces, even more so. ‘It would be good to write down everything I see there.

Over time, these notes, like seeds, can grow into stories!’ Preparing for the journey, he packed a travel inkstone and stocked up on a fair amount of ink so that he could scribble about everything without sparing any words. (Samurai carried a travel inkstone with a brush on their belt, right under their quiver, and it was called a yatate-no-suzuri). Ihara Saikaku Seven hundred ryō, for which they paid with their lives There is a proverb that says, ‘He who knows nothing is like Buddha.’ O-Natsu did not know about Seijuro’s death and was worried about him, but one day the village children ran past the house, singing: ‘They killed Seijuro, so kill O-Natsu too!’ Hearing this song, O-Natsu became alarmed and asked her wet nurse about it, but she did not dare to answer her and only cried. So it was true! O-Natsu’s mind was clouded.

She ran out of the house, joined the crowd of children and was the first to sing: “… Why should she live, pining for him!…‘ It was sad to see her. People tried to comfort her and stop her, but to no avail. Then tears poured from her eyes, but she immediately burst into wild laughter, shouting: ’Isn’t that passer-by Seijuro? The hat looks just like his… his straw hat… Ha-ha-ha…”

Her beautiful face was distorted, her hair was dishevelled. In her madness, she set off down the road, wandering wherever her eyes took her. Once she came to a mountain village and, caught by nightfall, fell asleep right under the open sky. The maids who followed her also lost their minds one after another, and in the end, they all went mad. Meanwhile, Seijuro’s friends decided to preserve at least the memory of him.

So they washed the blood from the grass and cleared the ground at the site of the execution, and as a sign that his body was buried there, they planted a pine tree and an oak tree. And it became known to all that this was Seijuro’s grave. Yes, if there is anything in the world worthy of pity, it is this. O-Natsu came here every night and prayed for the soul of her beloved. Perhaps at that time she saw Seijuro before her as he had been before. Days passed, and when the hundredth day came, O-Natsu, sitting on the dew-covered grave, took out her amulet dagger… They barely managed to restrain her. ‘It’s useless now,’ said those who were with her. ‘If you want to do the right thing, shave your head and pray for the departed for the rest of your life. Then you will be on the right path. And we will all take a vow too.’

These words calmed O-Natsu’s soul, and she understood what was expected of her. ‘What can I do? I must follow their advice…’ She went to Shōkaku-ji Temple and spoke to the holy father there. That same day, she exchanged her sixteen-year-old dress for the black robes of a nun. In the mornings, she would go down to the valley and carry water from there, and in the evenings, she would pick flowers on the mountain tops to place them before the altar of Buddha. In the summer, she would read sutras by lamplight every night without fail. Seeing this, people admired her more and more and finally began to say that Tsyuzohime must have reappeared in this world. It is said that even in Tajima, the sight of her cell awakened faith, and those seven hundred ryos were donated to the memory of Seijuro, to perform the full ceremony. At that time, a play about Seijuro and O-Natsu was written in Kamikata and performed everywhere, so that their names became known throughout the country, even in the most remote villages.

Thus, the boat of their love sailed on new waves. And our lives, like foam on these waves, are truly pitiful.

I will only mention those that touched my soul the most: ‘Good and evil do not travel long in the same carriage.’ Separate stories from the collection ‘The Roadside Slaughterhouse’ ‘Trouble sprouting from bamboo’ ‘Death on the waves makes everyone equal’ ‘How choice determined the truth’ ‘The society of one momme’ ‘Rice Cakes in Nagasaki’ ‘The World Plunged into Darkness’ and so on.

I will only mention those that touched my soul the most: ‘Good and evil do not travel long in the same carriage.’ Separate stories from the collection ‘The Roadside Slaughterhouse’ ‘Trouble sprouting from bamboo’ ‘Death on the waves makes everyone equal’ ‘How choice determined the truth’ ‘The society of one momme’ ‘Rice Cakes in Nagasaki’ ‘The World Plunged into Darkness’ and so on.