My grandmother was extremely hardworking. We used to call her ‘Abaai’. She was long-lived, blessed with a life of 104 years. Abaai was very diligent. She instilled in us the values of hard work, perseverance, and integrity. Until the age of 80, she would go to the fields. The term ‘backbreaking toil’ aptly describes her life. Her only son was my father, Mr. Vaijnathrao Taur.

My grandmother was extremely hardworking. We used to call her ‘Abaai’. She was long-lived, blessed with a life of 104 years. Abaai was very diligent. She instilled in us the values of hard work, perseverance, and integrity. Until the age of 80, she would go to the fields. The term ‘backbreaking toil’ aptly describes her life. Her only son was my father, Mr. Vaijnathrao Taur.

My father lost his paternal shelter when he was just about a year to a year and a half old. . Aabai became a widow at a young age, but she never lost courage. She took care of her son and grandchildren until she was 80 years old. Today’s Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar was then known as Aurangabad, the district headquarters. For the grandchildren’s education, Abaai lived with us in Sambhajinagar for seven or eight years.

Today, one can reach Sambhajinagar from Shivangaon in two hours. But back in 1964, it took us two days. We had to halt at Pokhari midway to catch the train at Partur. Partur railway station was 59 kilometers from my village. The entire journey to the station was by bullock cart, accompanied by our luggage – trunks, gunny bags, and sacks filled with essential items. There would be no space left in the cart. My father would then walk alongside the bullock cart. My father was known as ‘Bappa’ throughout the region. He also lived to be a hundred years old. His habit of walking continued until he was ninety. Even at that age, Bappa would easily walk thirty kilometers. He used to cover the thirty to thirty-five kilometer distance from Takarvan to Kumbhar Pimpalgaon on foot.

In 1964, Bappa became the Sarpanch (village head) of Shivangaon. Being Sarpanch involved a lot of travel and meetings with dignitaries. He went to meet the then Union Agriculture Minister, Punjabrao Deshmukh. Earlier, when we were children, he had visited the Rayat Shikshan Sanstha in Satara to seek the blessings of Karmaveer Bhaurao Patil. I was with Bappa when he met Shikshanmaharshi Mamasahab Jagdale. He also made it a point to meet Mr. Pandharinathrao Patil. However, once his term as Sarpanch ended, he never looked towards politics again. Meeting these eminent people made my father realize the importance of education. The land in Gangathadi was very fertile, but there were no educational facilities in the area. Illiteracy was rampant, making it easy for the rich and powerful to exploit the poor and lower-middle class. Most people depended solely on farming. Bappa understood that we, his children, needed to be taken away from farming in time and given an education.

In 1964, Bappa became the Sarpanch (village head) of Shivangaon. Being Sarpanch involved a lot of travel and meetings with dignitaries. He went to meet the then Union Agriculture Minister, Punjabrao Deshmukh. Earlier, when we were children, he had visited the Rayat Shikshan Sanstha in Satara to seek the blessings of Karmaveer Bhaurao Patil. I was with Bappa when he met Shikshanmaharshi Mamasahab Jagdale. He also made it a point to meet Mr. Pandharinathrao Patil. However, once his term as Sarpanch ended, he never looked towards politics again. Meeting these eminent people made my father realize the importance of education. The land in Gangathadi was very fertile, but there were no educational facilities in the area. Illiteracy was rampant, making it easy for the rich and powerful to exploit the poor and lower-middle class. Most people depended solely on farming. Bappa understood that we, his children, needed to be taken away from farming in time and given an education.

So, my father sent us siblings to Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar for studies. Later, I went to Khamgaon in Buldhana district for further education. There, in 1972, I completed my Homeopathy course. At the Khamgaon college, I was fortunate to have ideal teachers like Principal Kaviswar Sir, Dr. Captain Sane Sir (M.S. Anatomy), and Dr. Sannyas Sir (M.D. Calcutta).

After completing my education, my father arranged for me to stay in Nanded for my medical practice. I stayed with Dr. Wadekar (M.S. Surgeon) and Dr. Tejaswini Wadekar Madam. Dr. Wadekar Sir was a man of strict discipline. Both of them worked seventeen to eighteen hours a day. They were government medical officers and had also established their own 30-bed hospital. Dr. Wadekar Sir taught us the essence of patient care. His very personality was a testament to the ideal doctor-patient relationship. Patients came to the hospital from Parbhani, Jalna, Beed, Hingoli, Nanded, Yavatmal, and even Andhra Pradesh.

Dr. Wadekar treated patients with immense respect and affection, speaking to them kindly. Sometimes, he would address elderly patients respectfully as ‘Malak’ (Sir). He would drop elderly patients off at the station in his own car. Dr. Wadekar used to say, ‘If an elderly patient comes to you suffering from COPD with phlegm and doesn’t have a spittoon, offer your own hand. Do not feel inferior. One who feels demeaned by serving the sick should not become a doctor.’

Once, an elderly gentleman came as a patient from Barad. He must have been around 90 years old. He was suffering from constipation, hadn’t passed stool for seven to eight days. Hard fecal matter had formed lumps in his stomach. He was struggling with abdominal pain and lack of appetite. Sir told me, ‘Wear two gloves on your right hand, one over the other, and remove the fecal lumps from his stomach.’ This was, in a way, my test.

Dr. Wadekar taught us that while serving patients, a doctor must have no sense of shame or disgust, and no task should be considered menial or inferior. He was extremely vigilant regarding treatment and could not tolerate even a hint of negligence. Many such anecdotes about Dr. Wadekar Sir’s dedication to patient care come to mind.

One night at three o’clock, a hefty photographer from the town fell from the third floor of his building. There was a telephone line along the road. The phone wires ran across horizontally. The photographer fell directly from the third floor onto those telephone wires. Due to his weight, the wires sagged, bending the poles on either side, and the wires came to rest dangling one to one and some half feet above the ground. The wires had formed a cradle, preventing him from hitting the ground directly; he was suspended. The photographer must have weighed around 120 to 130 kilos. His residence was barely a hundred feet from the hospital. Upon receiving the information, we rushed with two thick sheets, lifted the photographer, and brought him to the hospital. I first examined his limbs, head, and abdomen carefully and admitted him under my supervision.

Midnight had long passed. Dr. Wadekar, having performed a C-section, was asleep. I felt the patient’s condition was stable. No visible injury was apparent, and there were no signs suggesting an internal abdominal organ rupture. At six in the morning, I informed Sir about the patient. The moment I finished speaking, I saw Sir’s face turn red with anger. He strode briskly, almost running, to the patient. He immediately ordered X-rays of the patient’s abdomen and limbs. I could feel Sir’s anger towards me. But two hours later, he called me and praised my treatment. However, he also advised me never to take such a risk again.

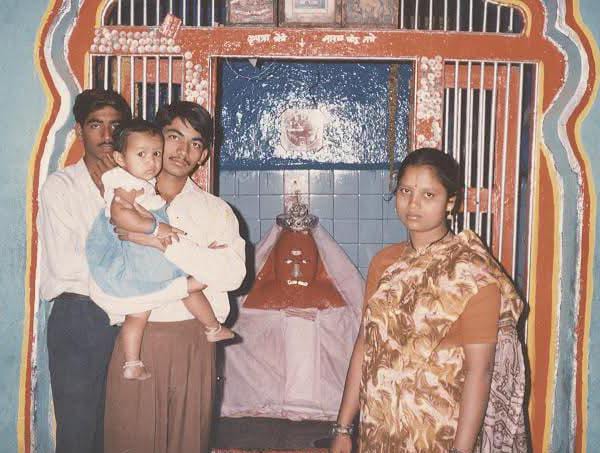

On the 2nd of January 1978, I started my practice in Kumbhar Pimpalgaon, taluka Ghansawangi, district Jalna. At that time, this village was in Ambad taluka of Aurangabad district. Later, in 1981, Jalna district was formed, and in the subsequent decade, the new Ghansawangi taluka was carved out of Ambad. Kumbhar Pimpalgaon was a small village with a population of two to three thousand. The village had a significant number of potter (Kumbhar) families. The Patilki (village headmanship) was held by the Kantole Patil family. Ragoji Police Patil, Hiralalji Kasliwal, and Sarpanch Sopanrao Patil Kantole managed the village affairs. In those days, nothing from the village would leak out. Most disputes were resolved amicably through discussion. No one would dare defy the word of these three respected elders.

Wednesday was the village’s weekly market day. People from the surrounding 30-40 villages would come to the market on foot, by bullock cart, or on horseback. It was a major market in the taluka. Kumbhar Pimpalgaon has two Maruti temples. One of them is ‘Pahuna Maruti’ (Guest Maruti). The villagers have a deep faith that this Maruti welcomes arriving guests, and it indeed feels true. The village morning would invariably begin with a visit to Maruti’s temple.

Rather than saying I started the medical practice, it would be more accurate to say ‘we’ started it. My wife, Mrs. Snehaprabha, is an Arts graduate. She affectionately understood my hectic schedule and the challenges ahead. At that time, there wasn’t a single female doctor in Kumbhar Pimpalgaon and its surrounding area, not to mention a severe shortage of nurses, sisters, or even midwives. My wife would assist me in serving patients. Back then, female patients were often neglected. The name of my clinic was ‘Nath Prasuti Gruha’ (Nath Maternity Home), which naturally attracted a larger number of female patients. My wife’s help was invaluable in conducting deliveries smoothly. Her presence also gave confidence to the women patients. This way, she contributed to our household income, allowing us to earn enough to educate our four children.

Besides maternity care, I also ran a general practice. I treated most cases of snake bites, scorpion stings, poisoning, gastroenteritis and dog bites. The clinic remained open day and night. Earlier, deliveries used to happen in homes with cow-dung plastered floors, in dark corners, on old dusty clothes. Dr. Wadekar Sir had advised us to use clean newspapers or raxine sheets.

When I started my rural practice, I initially had only a bicycle. I would use it to visit surrounding villages. Later, I bought a horse, because the bicycle would get punctured constantly. Moreover, most roads connecting the villages were mere cart tracks. During the monsoon, there would be knee-deep mud, making cycling impossible as the cycle would constantly get stuck. Later on, I purchased an HD motorcycle, then an Ambassador, and later an Inter Honda. I rode motorcycles for four decades. In the final years, an ambulance also stood parked at the clinic’s door.

The people of Kumbhar Pimpalgaon were very loving and selfless. A Banjara woman named Umabai used to come from three kilometers away, bringing us milk for about ten years. She would also bring vegetables, tender corn, beans, khoa, and edible gum. She would stay for hours after arriving. She became like a member of our family. We all would affectionately call her ‘Yadi’ (Mother). Yadi would scold my children with her stick, but would also shower them with just as much love.

The Godavari River flows about ten kilometers south of Kumbhar Pimpalgaon. I would wade through neck-deep water to visit patients in villages on the other side, even at night, carrying an extra set of clothes to change into.

There is a unique satisfaction in practicing in a village. You are present where a doctor is most desperately needed. In 1978, villages lacked roads, educational facilities, state transport buses, and even private jeeps. Patients needing deliveries, poisoning cases, snake bites, serious scorpion sting victims – all suffered tremendously. Ambad was 45 kilometers from Kumbhar Pimpalgaon. Jalna, which had decent medical facilities, was 80 kilometers away. Other nearby cities like Parbhani and Beed were over 100 kilometers distant.

In 1991, my father suffered a sunstroke. He ran a very high fever, had loose motions, and severe vomiting leading to dehydration. I administered plenty of saline, but the loose motions and dehydration wouldn’t subside. Bappa lost consciousness. I managed to arrange a private jeep from the village and, taking my father with me, reached the Government Medical College Hospital (Ghati) in Aurangabad (now Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar) by three in the morning. Treatment continued for 15-20 days, after which Bappa recovered completely, hale and hearty.

The people from the surrounding villages were very good-natured and pure-hearted. As a doctor, I had close ties with the villages around Kumbhar Pimpalgaon. I used to visit 30-40 villages in the vicinity. Calls for deliveries would come at all hours of the night, and I would never refuse. I would pick up my bag and kick-start my motorcycle.

One night, while going to Limboni village, about seven kilometers away, thieves blocked the road. They had placed a rubber pipe (dhamin) across the unpaved road. A powerful flashlight beam shone directly on my face. I was blinded by the light, but my face became clearly visible. The thieves saw me, though I couldn’t see them in the darkness. They recognized me; they were patients who visited the clinic.

The thieves said, ‘Doctor Saheb, you are very late today.’

I replied, ‘I just received a call now, so I left immediately. A woman in the village is in obstructed labor. It’s urgent.’

The thieves removed the pipe and cleared the way for me, advising me to go slowly. Most of these thieves and highway robbers were people in financial distress. Many of them would come to my clinic at odd hours. Most people knew me as the doctor whose clinic doors were always open. In my fifty years of practice, I never felt afraid of thieves.

I reached Limboni and started treatment. The labor pains had started, but due to the woman’s short stature and anemia, the delivery was not progressing. It was a critical situation, touch and go for both mother and child. The girl’s parents were pleading with folded hands for me to do my utmost. I reassured them, saying, ‘Both the baby and the mother will remain safe.’ I put in my best efforts and finally succeeded. The next day, at four in the afternoon, a normal delivery occurred. A baby boy was born. However, the patient’s family didn’t have a single rupee to pay my bill. I was in a real fix. At that time, a good man named Dagadu Patil Kale lived in Limboni. His word carried great weight. Villagers respectfully called him ‘Malak’ (Boss). I went to Dagadu Patil, narrated the entire incident in detail, and told him about the bill. I had spent over twelve hours at the patient’s doorstep, attending to the delivery and providing treatment. Dagadu Patil listened to everything attentively. First, he arranged for a proper meal for me. Then, he himself went to the patient’s house to settle the bill. As payment for the doctor’s fees, he handed over a cow named ‘Bagli’ to me.

Malak had the cow and her calf loaded onto a cart, along with a cartload of fodder, and sent them to Kumbhar Pimpalgaon. Subsequently, Bagli had many calves. We kept Bagli for ten years. A very close bond developed with Dagu Patil after that incident. He would come to Kumbhar Pimpalgaon on market days and would invariably stop by the clinic. Dagu Patil took the initiative and stood by me to get a house built. He personally supervised the entire construction. He carefully selected the wood and carpenters needed for the mezzanine floor. He used to say that a doctor must have his own home, no matter how small.

We grew very fond of Bagli, who had come to our home. Once, Bagli gave birth to a calf three kilometers away from the village. She wouldn’t let the herdsman or any others approach her; she probably felt insecure. Soon it was six in the evening. The sun had set, and darkness was deepening. The herdsman was distressed. Finally, he came to the clinic. The electricity was off, as usual. I was examining patients by the light of a kerosene lantern. The herdsman told me what had happened. Within half an hour, I walked to where the cow was. Bagli was red with rage, charging with wide eyes. I went near her and called out softly, ‘Bagli, Bagli,’ three or four times. Bagli calmed down. Then, carrying the calf on my shoulders, I walked home with Bagli following.

Patients would affectionately bring us grains, vegetables, milk, and other necessities. When my children went to Sambhajinagar for their education, seeing our difficulty, even my lunchbox would come from a patient’s home. Once, I went to the Patil’s place in nearby Dhamangaon for a delivery. A son was born there too. The joy of having a son was indescribable; daughters were welcomed hesitantly. It was very late at night, so I stayed over. For dinner, they served so much ghee in the bowl that my flatbread was completely submerged in it. For the next four or five days, even my body smelled of ghee.

Whenever a patient came at any hour of the night, I would unfailingly open the door and begin treatment. One night, four thieves arrived after committing a major robbery somewhere. They knocked on the door. Thinking they were patients, I opened it. Two of the thieves were completely smeared in blood. As per a doctor’s duty, I let them into the clinic. I arranged drinking water for them. One thief had been severely beaten. He had a deep wound. I stitched his wound, dressed the other injuries on his hands and legs, gave them injections, and sent them off. As they were leaving, they did not fail to place the full payment for the bill in my hand.

My home and clinic were the same. The clinic occupied six compartments on the ground floor, and our home was on the upper mezzanine floor. We often slept in the clinic itself. The Maharashtra Bank was at the far end of the lane. One night, the bank was burgled. The thieves broke open the bank’s safe and cupboards, brutally beat up the constable on patrol, and fled. The bank was barely 200 feet from our home. The bleeding constable came running unsteadily towards the clinic and collapsed on the platform outside. The bank’s siren started blaring loudly, waking us up. I looked out the window and saw the constable, drenched in blood, lying on the platform right outside the window. I switched on the bulb on the outer platform. The light made the pursuing thieves halt in the darkness. Sensing something amiss, I opened the door and brought the constable into the clinic. He was almost losing consciousness. I quickly treated his wounds, applied stitches, and dressed them. By then, police from the nearby station had also arrived. The theft case dragged on in court for many years. In the meantime, the constable was transferred elsewhere. But for many years after, whenever he came to Kumbhar Pimpalgaon, he would meet me. He would say, ‘Doctor Saheb, I am alive because of you,’ and holding my hand, would repeatedly express his gratitude.

Once, I received a call for a delivery from Ghonsi, a nearby village. Ghonsi was a small hamlet about 15 kilometers from Kumbhar Pimpalgaon. It must have been past eleven at night. Nevertheless, I took my motorcycle and left. It was a hilly terrain, with undulating hills and a gravel road full of potholes. After going five kilometers, the motorcycle got a puncture. A man from the patient’s family was with me. I handed him my bag, parked the motorcycle by the roadside, and walked the remaining ten kilometers. By the time I reached, it was around 1:30 AM. It was the rainy season. But I was happy to find upon arrival that the patient had already delivered. Everyone at home was joyous. I examined the baby and the mother and gave necessary post-natal care instructions. That day, I stayed at the house of Manikrao Kalyanrao Tekale from the village. He took excellent care of my arrangements. In the morning, he sent people to get the motorcycle’s puncture fixed. I returned to Kumbhar Pimpalgaon later that morning.

Another similar incident occurred during Holi. Holi festivities last for five to seven days. The day after Holi is Dhulwad. I received a call for a delivery at Hatdi, about thirty kilometers away. On the way, I passed through three or four settlements (tandas) – Viregaon Tanda, and the three Jamb Tandas. As I passed, the Banjara people playfully drenched me in colors. Lamani women formed a circle around me, singing songs and playfully beating me with sticks. They all knew me well; some were my patients. Calling out ‘Doctor Dada! Doctor Dada!'(o Doctor Brother, o Doctor Brother) they made my Dhulwad memorable. After escaping from the Lamani brothers and sisters, and giving everyone some money as is customary, I reached Hatdi at four o’clock. The delivery had already taken place. They had prepared a feast of Puran Poli to celebrate the new baby’s arrival. After attending to the mother, I sat down to eat with them. The patient’s family insisted and fed me the Holi special Puran Poli.

Various superstitions and folk practices regarding snakes are prevalent in villages. One night, a patient was brought running over twelve kilometers on the shoulders of five or six sturdy men, carrying a huge python in a pot, with a seven kilo stone tied on the head with a cloth! I praised them for bringing the patient quickly. They had even brought the python in the pot to show which snake had bitten him. They hadn’t let the patient move much. My first act was to free the patient from the burden of the stone. After administering first aid, I referred him to the Jalna Civil Hospital.

Since our region has water from the Jayakwadi dam all year round, sugarcane and soybeans are grown extensively. The soybean plants grow three to three and a half feet tall. Thorns, shrubs, stones on the field boundaries, and ditches mean snakes and scorpions are common. Patients with their bites and stings would come regularly.

Once, a 35-year-old man came from a village named Limbi. He was sweating so profusely that water was dripping from the wooden tabletop onto the floor. All his clothes were soaking wet. He was also shivering violently. I had to place a bucket under the table to collect the water. I immediately started treatment, setting up four IV lines. Still, the sweating wouldn’t stop. His BP showed no fluctuations. Coincidentally, my mentor Dr. Wadekar Saheb happened to arrive from Nanded at that time. He examined the patient, suggested some antibiotics, and advised continuing the IVs. After midnight, the patient began to feel better. He was admitted for two more days and then discharged.

Our clinic was very small. There was no facility to admit patients. Yet, sometimes four maternity patients would arrive simultaneously. Every delivery was conducted normally. When a delivery patient came, they were accompanied by one or two bullock carts and seven or eight people. So even at night, the clinic doors wouldn’t be closed, because people would be sitting or sleeping in the bullock carts parked on the platform outside or across the street.

One afternoon, an elderly woman came to the clinic, her head drooping, in a semi-conscious state with red discharge oozing from her mouth. Her BP had dropped. Her pupils were constricted to pinpoints. I examined her carefully and diagnosed poisoning. I administered IV Atropine and started an IV drip. Within a couple of minutes, Dr. Nilesh Pawar (M.S. Orthopedic), who had come from Parbhani for a visit, arrived. He saw the patient and immediately identified it as a snake bite. We administered IV Atropine again and referred her to the Ghanti for further treatment. Two weeks later, that lady, whose surname was Bhise, came to the clinic and fell at my feet.

I used to make fifteen to twenty visits per month. I would either reach the village for my visit as the sun rose, or leave around four in the evening and return to Kumbhar Pimpalgaon by six-thirty. I would also visit the homes of patients who had delivered, three or four days later. I had many elderly patients. If a patient was serious, I would stay there for three to four hours, until the patient was stable.

It was a Wednesday, the weekly market day in Kumbhar Pimpalgaon. The month of July, monsoon season. In the evening, I received a message that a grandmother in Limbi had been stung by a scorpion. The main gravel road to Limbi extended two kilometers to the east, beyond which was a cart track. It was evening, the sky filled with dark, ominous clouds. I was speeding on my motorcycle. While on the cart track, a heavy downpour began. The track was black soil. I neared the main road, but water had accumulated in the ditch (barashi) due to the rain. The motorcycle couldn’t climb onto the road in the torrential rain; it started sliding down five or six feet. The tyres were stuck in the mud, not moving an inch. Finally, leaving the motorcycle there in the ditch, I waded through knee-deep water, in pitch darkness illuminated only by the flashes of lightning raging across the sky, and somehow reached Limbi at ten o’clock at night. I started treating the grandmother. I rested there that night, shivering with cold. The next morning, while returning, I saw the motorcycle was not where I had left it. Streams of water had broken out everywhere. The motorcycle had been swept away about 200 meters and got stuck against a lemon tree.

Respected Daulatraokakaji Taur, Ramraoji Taur, and Babasaheb Kale would often visit the clinic. Kakaji, in fact, came regularly for 15 years and would sit in the clinic for three or four hours. Kakaji was a man of great virtue. If Kakaji didn’t come on any day, I would go to Limbi to meet him. Many patients, on their deathbeds, would remember me. I would unfailingly go to meet them.

For the past seven or eight years, I have been living in Sambhajinagar. Whenever I get time, I still go from here to meet my old patients. Once, in January 2019, on the night of Friday the 10th, I felt a strong urge to see Kakaji. I started reminiscing about the time spent with him. I couldn’t sleep till late at night. The next morning, I woke up, caught the first bus from Sambhajinagar to Kumbhar Pimpalgaon, and traveled 140 kilometers to reach Limbi.

Kakaji’s cough had worsened. He couldn’t lie down. Despite his condition, Kakaji talked for three to four hours. He inquired about my daughters. He handed me his phone diary. He couldn’t articulate what he wanted to suggest. Finally, I understood he wanted me to call my daughters. Kakaji passed away at three o’clock that afternoon.

I have rendered medical service for over fifty years. Practicing in a village for four decades gave me the opportunity to serve the people of the villages, the huts, and the settlements (wadi-tandas). Money was needed, I needed money for my children’s education and to support my family, but I never practiced merely to earn money. Even today, the rural folk have little money; back then their condition was even worse. My happiness came from seeing people get better, seeing my patients recover completely. As a doctor, at this moment, I am content. I take justifiable pride in having remained true to the oath I took when I received my medical diploma.

(Dr. Bhaskarrao Taur provided medical service for 55 years in a small village on the banks of the Godavari River. Thousands of children were born safely at his ‘Nath Prasuti Gruha'(Nath Nursing Home). He now resides in Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar. Former patients he treated still make it a point to come and meet their doctor. Contact: +91 9420461437, drshahajitaur@gmail.com)

Photographs

1. Dr. Bhaskarrao Taur at his Nath Nursing Home.

2. The then Health Minister of Maharashtra state, Rajesh Tope, felicitated Dr. Taur along with his wife for his uninterrupted medical service in rural areas.

3. Nath Maternity Home, Kumbhar Pimpalgaon

4. Pahuna Maruti Temple