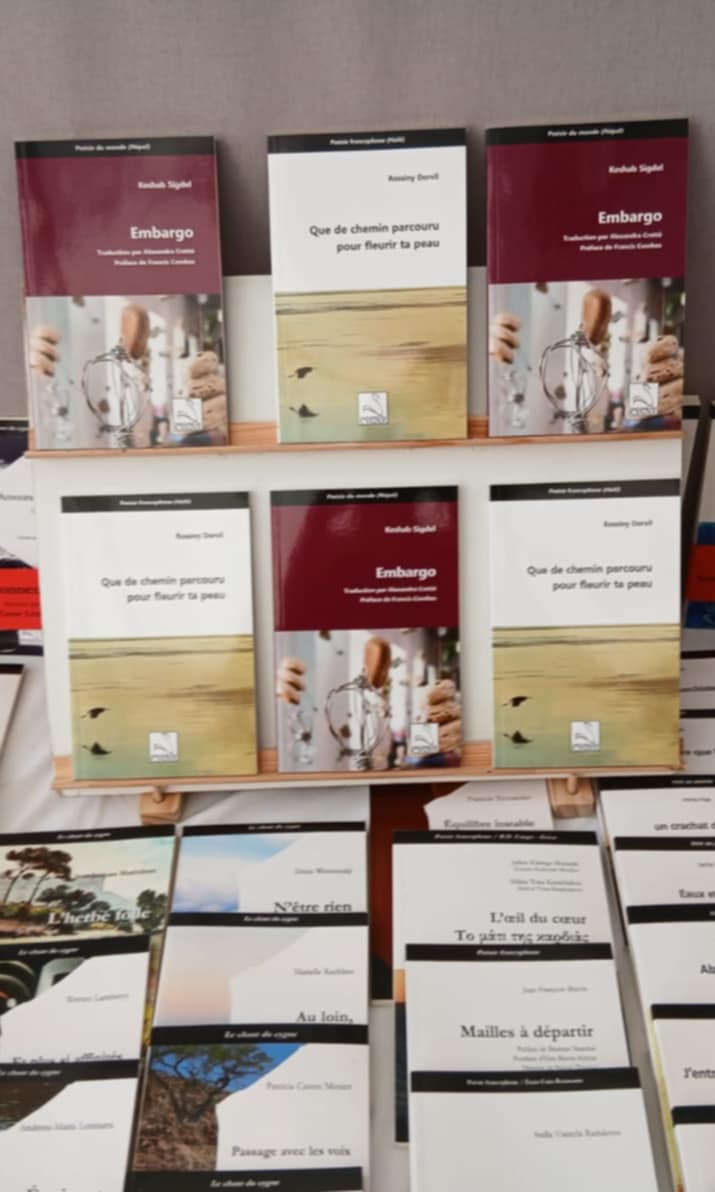

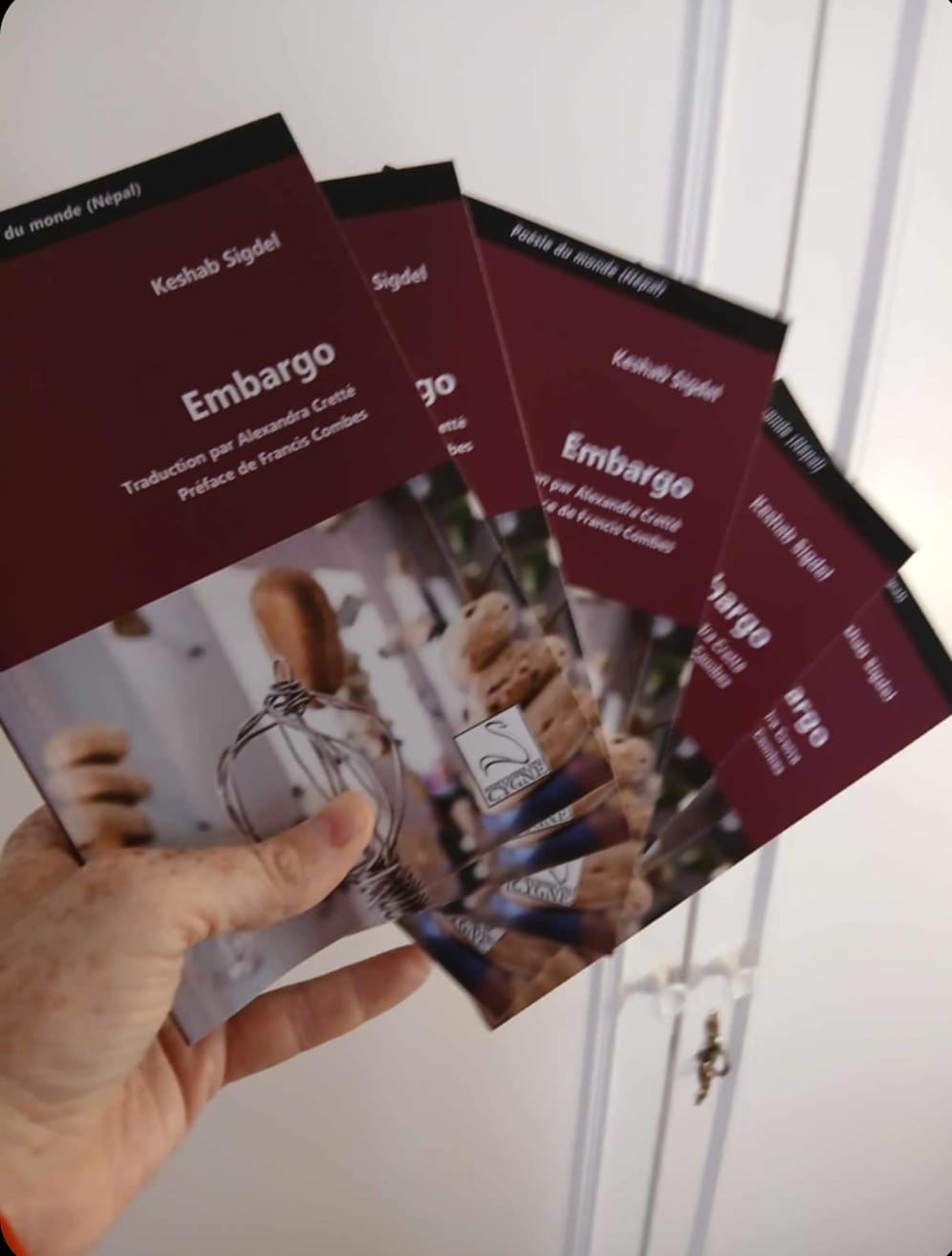

With Embargo, Nepali poet Keshab Sigdel invites us on an inner journey through the plural landscapes of contemporary Asia. Between the Himalayan lakes, the industrial lanes of China and the silent farms of Nepal, he traces a lucid, cyclical poetry, rooted in the faults of the world and the rustling of the soul.

Interview with a rare voice, both fraternal and universal.

LE NATIONAL: How could you define your relationship with poetry and with language?

KESHAB: Language has always fascinated me. I grew up in a multicultural and multilingual society. As a child, I was amazed to realize that the language I spoke and understood was not enough to fully grasp the cultural activities and underlying concepts expressed in other languages. By the same token, there are many cultural practices and concepts in my own culture that are unique and untranslatable. No other language has equivalent terms that can fully convey their meaning. I believe these cultural metaphors help shape my unique worldview. I understand the world through languages. And the world is not the same for everyone. For the rich and the poor, the world is different. For the young and the old, for white people and people of color—this world is not the same. Language helps us realize that difference.

I imagine who I am through language, or by similar token, people create an image of my through their language. My choice of words, my accent, its colloquialisms, and formal standards—they all define who I am in relation to others. But I also realize that my own language alone is an insufficient tool to comprehend complex social and human processes—these are better understood when I am supplemented by other linguistic and cultural frameworks. This line of thought leads me to reflect on the importance of embracing multiculturalism and multilingualism. By this, I don’t mean we must subscribe to all cultures and languages simultaneously, but that we must acknowledge their existence and respect those who live through languages and cultures different from our own.

Poetry has touched my life in many ways. My mother, a deeply religious woman, sang hymns in Sanskritized poetic forms. In school, we were taught verses from great Sanskrit epics like the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. The lyrical quality of those verses, combined with their powerful messages, made a deep impression on me. But during middle school, I came into contact with underground political leaders who often visited our home. Some of them brought publications that included poetry advocating freedom human rights. I was fascinated by how such writing could influence society and even challenge political systems. At that young age, I had already begun to sense that poetry carried a promise to change—even if not the power to change.

Poetry has touched my life in many ways. My mother, a deeply religious woman, sang hymns in Sanskritized poetic forms. In school, we were taught verses from great Sanskrit epics like the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. The lyrical quality of those verses, combined with their powerful messages, made a deep impression on me. But during middle school, I came into contact with underground political leaders who often visited our home. Some of them brought publications that included poetry advocating freedom human rights. I was fascinated by how such writing could influence society and even challenge political systems. At that young age, I had already begun to sense that poetry carried a promise to change—even if not the power to change.

I don’t clearly remember the title, but one of my poems was published by a political activist living in exile in India. After the dawn of democracy in my country, things did not go well. Internal conflict and corruption were devastating the nation. Poetry became my only means of sustaining hope. As I grew up and started working professionally, my informal spaces for self-expression shrank. I had to rely on poetry to express myself. Poetry became a refuge for my personal conscience, a space to keep my sanity alive. That is why I often struggle to explain what exactly poetry means to me.

LE NATIONAL: How can the title of a poem, Embargo, become the title of the book?

KESHAB: The title of my poetry book Embargo reflects a sense of self-censorship, especially when processing personal emotions. But it also raises the deeper question: Who am I as a thinking being? In a society built on a value system designed to serve those in power, what can I think about? I reflect on how I consume the things capitalism offers, how my children are compelled to fit into economic and ideological frameworks—whether through education or employment. Our interests and desires are shaped not by what our hearts long for, but by what sells in the market, by what others consider valuable. If we are merely “subjects” molded by a pervasive ideology, we are already living under an embargo—an invisible restriction on our lives. This embargo interferes in every aspect of our personal and social existence. It may sound vague or far-fetched, but as poets and activists, we aim to ensure individual freedom for everyone. To reach that goal, we must create an environment where our conscience prevails. Metaphorically, we seek to cancel all embargoes imposed on us and on ordinary people around the world.

LE NATIONAL: The book publication crosses many geographies. Why these routes?

KESHAB: The publication of my book in Paris feels like a pleasant coincidence. I’ve never been to Paris, but as a university student, I read many French writers and philosophers, and they had a profound impact on me. France has long stood as a literary and political avant-garde for the world. A few of my poems were translated into French by the renowned French poet Francis Combes. Later, I met the poet and professor Alexandra Crette at a poetry festival in Colombia. I don’t know how, but to my good fortune, she took an interest in my work and offered to translate a selection of my poems into French. I was reluctant at first—I’ve always been shy about self-promotion. But now the book is out. I hope this French translation will open new avenues of cultural dialogue—not just between two nations but between two civilizations, two linguistic and cultural regimes.

I’m not interested in exploring only similarities. I want to understand and respect differences. As someone who has long advocated for multiculturalism and promoted humanitarian values through dignity and justice campaigns, I see this publication as a significant step forward. That said, I do feel a bit anxious about how French-speaking readers will receive my poetry. Since I don’t speak or understand French, I remain uncertain about how the social and cultural nuances of my world will travel into another language. But the translator Alexandra Crette is not only a brilliant poet and critic, she is also an activist. I fully trust that she has skillfully handled the cultural dynamics involved in this translation. She played a key role in making this book happen. I owe much to her love and friendship.

LE NATIONAL: Does daily life play an essential role in your writing?

KESHAB: Of course, there are moments when I try to live as myself, to think as myself. But these often turn out to be illusions. We are so deeply shaped by our surroundings and the people we interact with that nothing remains as a “pure self.” Our writing—our literary and social activism—is a constant resistance against unfair regimes. Even when I know the change I dream of may not happen in my lifetime, there is still a force that drives me to pursue that “currently impossible project.” I believe that force is hope. And my writings are influences by these phenomena.

Le National: Your poetry is deeply engaged. What is the poet’s role in a world in crisis?

KESHAB: I believe I’ve already hinted at the poet’s role in society. But it becomes more difficult to speak about that role during times of crisis. We organize solidarity campaigns for people in Gaza, for instance. But how meaningful are our words when people there have nothing to eat, when their family members are killed, when their homes are destroyed? This horror, this collapse of humanity, is beyond words. Poets are creatures of words. There’s a limit to what we can do.

But I try not to be overly pessimistic. I often receive messages from my Palestinian friends or acquaintances from other war-ravaged countries for some voices we have raised in their support. When in crisis, people can survive without food for a few days, without shelter for longer. But they cannot survive without hope. Hope is the crux for survival. I think poets can create sparks for such hopes. In a world torn apart by religion, politics, and language, poets try to find threads to connect people. Even in fragmented societies, they offer victims of crisis a sense of hope, extending love and kindness through words.

LE NATIONAL: You are also a passionate translator. What does this mean to you?

KESHAB: I’m not sure if “passionate” is the right word for the translation work I do. But I’m certainly not a “professional” translator in the commercial sense. I’ve been teaching Derrida at university, who reminds me of the untranslatability of languages and cultures. Yet, there’s no other option. We must translate if we want to expand the space for cultural collaboration, if we want to understand others more deeply. Translation is an “impossible necessity,” essential to the dignity and justice that poets and creative writers envision. It’s a strategic tool for reaching beyond our national and cultural borders.

I’ve translated hundreds of individual poems by poets from Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Americas into my native language. I’ve also translated many Nepali poets into English, the only global language I can work with. These English translations have helped further translations into other languages. I’m aware of the risk of translating a translation. Plato might have called it being “twice removed from reality.” But for me, even that process is a way of getting closer to distant people and cultures.

LE NATIONAL: You teach the literature of trauma. Does it influence your writing?

KESHAB: I teach a variety of courses: Nepal Studies, Cultural Studies, Poetry, and Literary Theory and Practice. You’re right—I’ve also taught courses on Literature of War, Conflict, and Trauma. Last year, I was invited to lecture on resistance literature at Tehran University in Iran. I’ve studied the trauma caused by the Partition in India and Pakistan and the civil war in Sri Lanka. A few years ago, I visited local Tamil communities in war-torn Jaffna. My own country endured a decade-long civil war that left lasting socio-economic scars. While political settlements have resolved these wars at the surface—through ceasefires and peace agreements—the people most affected continue to suffer, passing trauma from one generation to the next. Even though the people in power have deliberately ignored these facts, as both an ordinary citizen and a creative writer, I cannot ignore this deeply infected reality.

LE NATIONAL: A key poem in Embargo?

KESHAB: As a poet, this question is perhaps the hardest to answer. It’s not just about the difficulty of judging my own writing—it’s also a political and ideological question. When someone asks about my “key poem,” I always wonder: by what standard? Gaza is burning. More people are dying from hunger and disease than from bombs. A mother is shot while her infant is still suckling. Can we really decide what poem is more important or urgent in the face of that horror?

I write about hope. That’s all I can do. What instills hope differs from person to person, from context to context. But any poem that can spark or sustain hope—I consider that a key poem. Forgive me for this roundabout answer, but I don’t believe this question has a direct one-to-one answer.

LE NATIONAL: What are your projects?

KESHAB: Apart from my university teaching and research, I edit Poetry Planetariat, the publication of the World Poetry Movement. I’m also working on a new poetry collection in Nepali and my first novel, which explores the Nepali civil war. I serve on the translation committee of the Nepal Academy, our national literary institution. I am working on two more translation projects. I’m also involved in civil rights activism in Nepal. All of this keeps me very busy.

LE NATIONAL: A final word?

KESHAB: This interview came as a pleasant surprise in the context of the French translation of my poetry book Embargo. I thank you for the opportunity to share my reflections. I look forward to hearing from French readers—their thoughts, discomforts, or joys while reading a poet from a different geography and culture. I have deep admiration for the French language and culture, and I feel honored to be published in French. I sincerely hope that more such dialogues and exchanges will continue—so we may better understand one another, and foster mutual respect across literatures and cultures.

Interview by Godson MOULITE