Ali Al Ameri carries within him a geography shaped by exile and journeys. Born in the village of Waqqas, Jordan, to a family displaced from Beisan during the Nakba of 1948, he grew up in the Jordan Valley, at the crossroads of borders and historical divisions.

1- Your family was displaced during the 1948 Nakba. How has this exile shaped your life and writing?

– Exile is a sandy land, always reminding me that I stand on a shifting geography during a seismic time. Although this is metaphorical, I was actually born in Waqqas village, and spent my childhood in Qulay’at village, both in the Jordan Valley, which constitutes a seismic belt within the Dead Sea Rift. Here, the metaphor and reality perfectly match, in a poignant formula. This exile, which I might more accurately call it the exile of the forced displaced, I did not choose voluntarily, just as the 950,000 Palestinians who were displaced and uprooted from their homes and ancestral lands during the 1948 Nakba did not choose this forced fate. From that tragic moment, the term “Palestinian diaspora” was formed. Exile, in this uprooting sense, becomes an internal sign, making me feel as though I am living in a temporary place and at a temporary time. This sensation generates a silent pain that seeps into the self. But on the other hand, my life in exile always points to my occupied paradise, not the lost paradise. Consequently, exile digs deep into both the soul and language, as pain and hope intertwine in a single alloy. Life in exile is a suspended, trembling, and fluctuating existence. All of this is automatically reflected in the water of writing, as poetic language flows from this spirit suspended in time and geography.

2- What does the Jordan Valley, where you grew up, mean to you?

– The Jordan Valley represents the first threshold of the senses, as I lived a wild childhood in Qulay’at village, located on the border with northern Palestine. My village is a neighbor of the Jordan River, a witness to displacement, a playground, an open wild theater for the first words and the first colors, and a cupboard of sweet and bitter memories. When I was five years old, the June 1967 war broke out. We slept in a cave in the mountains before my family fled to the town of Al-Sarih, near Irbid, northern Jordan. I completed my elementary and middle school education at a school run by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA). Scenes from that war are still etched in my memory: enemy warplanes tore through the village sky at low altitude, on their way to bomb Jordan’s airports and other sites. We would rush to a small family shelter my father had dug near a large rock in front of our house. My grandfather (my father’s father) would ride his horse, inspect the fields, and return to us with vegetables. The Zionist occupation had shelled our house, but the artillery shell landed just meters before it, and exploded, creating a wide, deep crater that later collected rainwater. Scenes of war are still vivid in my memory, including the images of the Fedayeen in their camouflage uniforms and Kalashnikovs, and the Israeli Zionist occupation tanks captured by the Jordanian army during the Battle of Karameh on March 21, 1968, which resulted in a joint victory for the Palestinian Fedayeen and the Jordanian army. On the other hand, I still remember the love letters I used to bury under a wild Sidr shrub in the mountain. In my village, the wilderness was my first teacher. My brothers and I would walk to the Jordan River and swim in the shallow areas, as if we had been baptized in the holy waters like the Palestinian Christ, carrying the cross of our diaspora. In that village, we made our own toys from wires and empty cans, and we would make kites and compete in launching them into the village sky. Later, the occupation warplanes would come and scratch the skies of our childhood. Many of my childhood memories are part of my personal memory and the memory of my brothers and all the children of the village, just as they are part of the memory of the place. From our home, we watched the flashes of bullets and flares and heard the sound of explosions during operations carried out by Palestinian Fedayeen descending from the Taibah Valley in Jordan to the west of the Jordan River. In the Jordan Valley, I became acquainted with many plants, flowers, trees, animals, and wild birds. We lived in a mud house with reeds roof and wooden beams covered with a layer of cement. We didn’t know about electricity back then, so we read by the light of a lantern. My village witnessed my childhood writings and my first drawings, and my childhood is still present in my poems because it is the repository of images, memories, and Palestinian stories narrated by my grandfather, grandmother, father, and mother. In my childhood, my grandmother was a narrator of folk tales, which I later learned have mythical roots. A story migrates orally across places and times to become an open treasury of the imagination.

3- What does translation, through twelve languages over the world, bring to your message?

– Translation is a tongue that unites all languages, thus forming multi-directional cultural bridges between peoples. It is well known that translation plays a major role in building civilizations. It enabled the Arabs to preserve the Greek heritage and transmit it to Europe and the West in general, with the new achievements contributed by Arab and Muslim writers, scientists and philosophers. During the Abbasid era of Al-Ma’mun, translators were rewarded with the weight of their books in gold. This is a clear indication of the importance placed on translation, given its significant role in the human renaissance.

In terms of my poetic experience, my book “Enchanted Thread” was published in Spanish by the House of Poetry in Costa Rica, and numerous poems have been translated into twelve languages. At the initiative of my friend, the poet Alexandra Crete, the Tunisian poet and translator Arwa Ben Dhia continues to translate “Palestiniada” into French. This means that my poetry migrates to other readers, to other cultures, and to other languages. Consequently, my aesthetic, intellectual, national, and humanitarian message crosses the bridge of translation, becoming borderless. This arrival creates a kind of dialogue through poetic text, one that cannot be achieved without translation, which contributes to the dissemination of beauty and human values based on universal brotherhood, not on the globalization of hegemony. Translation enables the migration of the self to the other, and enhances understanding, cooperation, and love. Poetry expands the existence, and translation enables us to read the other, to travel across time and geography, and thus enables us to share aesthetics, ideas, and experiences with others.

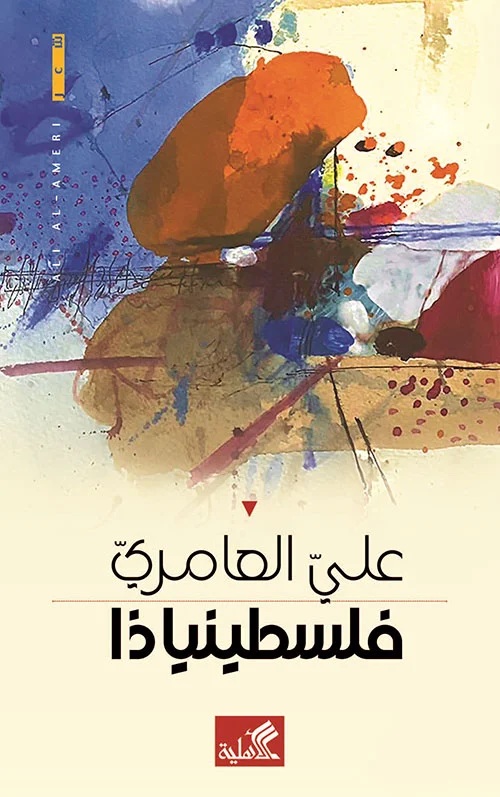

4- What is the story behind this book, “Palestiniada”, which won an award in 2024?

– My poetry book, “Palestiniada”, was actually published on October 4, 2023, three days before the October 7 events in Gaza. As is customary for publishers who release books at the end of the year, the publisher marked the year 2024 on the edition of this book, and its first book signing took place in November 2023, during the 42nd Sharjah International Book Fair. “Palestiniada”, whose title combines the names “Palestine” and Homer’s “Iliad”, won the Palestine World Prize for Literature, held in Baghdad at the end of 2024.

The book, which I dedicated “To my grandfather, my father, and my mother, who taught me the wisdom of trees”, comprises a single poem, multi-voiced and multi-rhythmic, employing dialogue, narrative, and drama, as well as popular, historical, and mythological heritage references. These include elements from the Iliad and Odyssey, such as Penelope’s awaiting the return of Ulysses, the wooden horse, and the sacrifices of the Trojans.

I worked to fill the text with spatial, natural, and spiritual dimensions, using the names of Palestinian villages and cities, wildflowers, plants, trees, Islamic and Christian holy sites, and Sufi shrines. It also includes references to the Kebaran civilization, named after the Kebara Cave in the south of the Palestinian city of Haifa, and the Natufian civilization, named after the Natuf Valley, located northwest of Jerusalem in Palestine, and the Canaanite civilization, as well as subsequent historical stages. In the poem, the memory of the first place, Palestine, intersects with the memory of the atlas of displacement and diaspora, the memory of grandfathers and grandmothers, fathers and mothers, the memory of grandsons and sons, the memory of the Nakba and Naksa, and the memory of war. Just as the memory of the Jordan River intersects with the memory of the Fedayeen, the memory of the key to the house, the memory of childhood and the Quleiaat village, the memory of the Battle of Karameh, the memory of Palestinian poetry, the memory of revolution, intifada, and resistance, and the memory of Palestinian stone.

- Is “Palestiniada” mainly a cry of hope, memory, or pain?

– The book brings together all of these elements, as pain and hope intersect, embodying the aesthetics of Palestine’s nature, its historical depth and civilizations dating back thousands of years, and the relationship of the Palestinian to his land, his home, and his rights to the land of his ancestors. It also demonstrates the Palestinian’s connection to the love of life and beauty, on the one hand, and his willingness to sacrifice for the homeland and his resistance to the Zionist occupation, on the other. The book “Palestiniada” constitutes a poetic narrative that counters the fabricated narrative of the occupation, which is based on myths, forgery, distortion, and lies. The writer and critic, professor Ibrahim Al Saafin wrote in the book’s introduction: “Ali Al Ameri, in this poetry book, which he chose a title closely related to the epic, presents the modern Palestinian epic in the adherence of the Palestinian people to their identity and their land, whether on Palestine land or in the diaspora.”

6- You are a poet, journalist, and artist. How do you find a balance these different roles?

– The day is for the job, and the night is for me. These three fields also intersect in many aspects, especially since the relationship between poetry and painting is profound, as both stem from the same source of creativity.

7- Do you believe that art is still capable of changing society and speak out against injustice?

– Literary and artistic creativity in all its forms has played a fundamental role in the history of humanity. In the beginning, art was a “talisman” against unknown beings and phenomena that humans considered mysterious. This role has continued with different meanings. Writing can be viewed as the “herb of eternity”, and Gilgamesh’s journey to the depths of the sea in the Sumerian myth is a metaphor for an inner journey into the depths of humanity, where immortality and mortality exchange their messages like twins. Both journeys are adventures amidst the dangers lurking in the deep darkness of the waters and the darkness of the self. In this sense, it seems to me that writing is the password to profound beauty, the password to resisting ugliness, and the password to resisting injustice, hegemony, occupation, and oppression. In the beginning, there was “NO”, and exile was a punishment. If we return to the clay and stone tablets of ancient civilizations, we find the survival of the word, whether drawn, engraved, or carved. Throughout the human journey, creativity has been a reservoir of questions and dreams, a generator of awareness, and a catalyst for change and protest against injustice.

8- You talk about bringing together what history has scattered. What still needs to be rebuilt?

– The true history remains forgotten, obscured, or ignored, because the “victors” are the ones who wrote official history, while the truth lives in the testimonies of the victims. Therefore, justice requires restoring dignity to the persecuted and the oppressed, making their voices heard, and rendering their suffering visible in the sunlight.

9- What message would you like to leave to today’s young poets?

– My message to myself and to other poets is always to continue reading, to explore poetic sensibilities from around the world, and to stand with the oppressed and marginalized.

10- Is your greatest dream to return to your homeland or to create a new way of belonging there?

- Returning to Palestine is my greatest dream, as it is the dream of millions of Palestinians living in exile. Nothing equals the meaning of freedom.

11- In your opinion, what can poetry achieve in the face of war and exile?

– Poetry constitutes a map of the living conscience of the world. It is the human compass, the password for a life governed by justice, mercy, love, beauty, cooperation, and participation. Poetry is the lexicon of hope, and the voice of the voiceless.

In war, poetry reminds us not to fall into despair. In exile, it grants us luminous patience, enabling us to bear the burden of distance and waiting. The poetry restarts the energy of hope, and builds a dialogue across borders, in the face of intercontinental missiles. During the crimes of genocide and famine against the Palestinian people in Gaza during two years, we saw how the conscience of peoples all over the world was stirred in a great movement of solidarity with Palestine. People used poems, drawings, visual scenes, symbols, posters, music, and songs to protest the genocide perpetrated by the Zionist occupation with the assistance of Western countries, led by the United States of America, which practices what I might call colonial hallucination. We have seen how Palestinian poetry in general, and in Gaza in particular, is being highlighted, and numerous anthologies of Palestinian poetry have been published in various languages around the world. Poetry will remain the heartbeat of humanity at all times.

Interview by Godson Moulite for The National in Haiti.

///////// Bio /////////////////

ALI AL AMERI

Ali Al Ameri, a poet and painter, his family was forcibly displaced from Beisan, Palestine, to Jordan during the Nakba 1948, following the Zionist occupation of Palestine. He was born in Waqqas, Jordanian village, 1962, and spent his childhood in the border village of Qulay’at, in the Jordan Valley. He completed his primary and preparatory education at a UNRWA.

He has participated in Arab and international poetry festivals and readings in Palestine, Jordan, UAE, Yemen, Iraq, Tunisia, Syria, France, Spain, Costa Rica, Macedonia, Kosovo, Morocco, Colombia, Venezuela, and Turkey. He has also participated in “remote” forums held in Italy, Macedonia, Azerbaijan, and Bolivia.

He has served on the judging panels for several literary and fine arts awards. He was a founding member and artistic director of the Dubai International Art Symposium (DIAS) in 2013 and 2014. He has participated in international art symposiums in Jordan, UAE, Greece, Macedonia, Romania, Georgia, and Egypt. He has also participated in group exhibitions in Jordan, UAE, Palestine, Kuwait, United States, Romania, Greece, Georgia, and Egypt. He held his first art exhibition, “Deep Mirrors,” in Amman in 2015.

Professional Life:

Editor of Aram Press; Cultural and Media Officer at Philadelphia University in Jordan; Head of the Cultural department of Al Arab Al Yawm newspaper from its inception until the summer of 1999; Editor of Al Khaleej newspaper in Sharjah (1999 – 2005); Head of the Culture and Arts department of Al-Emarat Al Youm newspaper in Dubai (2005 – 2016); and currently works as the Editorial Manager of “Kitab” magazine, published by Sharjah Book Authority, since 2017.

Publications:

– “This Is My Intuition .. This Is My Vague Hand”, poetry, Aram House for Studies and Publishing, Amman, Jordan, 1993.

– “White Eclipse”, poetry, Arab Foundation for Studies and Publishing, Beirut, 1997.

– “Enchanted Thread”, poetry, first edition, Ministry of Culture, Amman, 2012; second edition, Dar Fadaat for Publishing and Distribution, Amman, 2013.

– “Enchanted Thread”, poetry, published in Spanish, translated by Abeer Abdel Hafez, House of Poetry in San José, Costa Rica, 2014.

– ” Manuscript of Ink .. Poets Talk About Childhood, Love, and Exile”, Interviews, Al Ahlia Publishing and Distribution House, Amman, 2020.

– “The Book of Intuitions”, a poetry anthology, Khatout wa Dhilal Publishing and Distribution House, Amman, 2021.

– “Palestiniada” poetry, Al Ahlia Publishing and Distribution House, Amman, 2024.

Book Editing:

– “The Kinship of Alphabets” (editing), Sharjah Book Authority, UAE, 2022.

– “The Imprint of Andalusia” (editing), Sharjah Book Authority, 2023.

– “The Migration of Languages” (editing), Sharjah Book Authority, 2024.

Membership of Associations:

Jordanian Writers Association, General Union of Palestinian Writers, General Union of Arab Writers, Jordanian Journalists Syndicate, Erzal Culture and Arts, World Poetry Movement (WPM).

Awards:

– Palestine World Prize for Literature, Baghdad, 2024, for his poetry book “Palestiniada”.

– Andrés Pillo Order, First Class, Caracas, Venezuela, 2025.

Languages into which his works have been translated:

“Enchanted Thread”, poetry book, published in Spanish by the House of Poetry in Costa Rica, titled (Un Hilo Embrujado), translated by Abeer Abdel Hafez, 2014.

Several of his poems have been translated into 12 languages: Spanish, Italian, German, English, French, Macedonian, Albanian, Azerbaijani, Chinese, Greek, Bosnian, and Turkish.

Studies on his works:

– “The Mirror and the Word.. The Image of Modern Poetry in Jordan”, by Diaa Khudair, Arab Foundation for Studies and Publishing, Beirut, 2001.

– “The Poetic Flash.. The Magic of Formation, the Eloquence of Essence”, by Mohammad Saber Obaid, Department of Culture, Sharjah, UAE, 2023.