The sunset was about to complete its course on November 20, 2025, when Moscow’s cold autumn wrapped its quiet breath around the hills of Poklonnaya, and I made my way toward the Victory Museum (Central Museum of the Great Patriotic War) accompanied by my companions: my Chilean friend, the inquisitive journalist Patricio; and the gentle translator from the World Peoples Association, Olga, whose soft Russian whispers healed even the harshest memories. Driving us through the crowded streets was Andrei, who resisted the traffic and endless signals with philosophical commentary.

The sunset was about to complete its course on November 20, 2025, when Moscow’s cold autumn wrapped its quiet breath around the hills of Poklonnaya, and I made my way toward the Victory Museum (Central Museum of the Great Patriotic War) accompanied by my companions: my Chilean friend, the inquisitive journalist Patricio; and the gentle translator from the World Peoples Association, Olga, whose soft Russian whispers healed even the harshest memories. Driving us through the crowded streets was Andrei, who resisted the traffic and endless signals with philosophical commentary.

The slow movement of traffic turned the car into a classroom: sometimes history, sometimes observations of passersby, with plenty of details about Russian names. In Russian, the ending of a name usually indicates its gender. If a name ends with a consonant, it is masculine, like Ivan (Иван) or Sergey (Сергей). If it ends with -a or -ya, it is feminine, like Anna (Анна) or Maria (Мария). This rule helps identify the gender easily and affects the adjectives and verbs associated with the name. In Russian, surnames also distinguish sons from daughters through their endings. Male surnames often end in -ov, -ev, or -in, like Ivanov or Petrov; for females, an -a is added, becoming Ivanova or Petrova, indicating she is the daughter of Ivan or Peter. I joked that this being a language lesson, we could stop here and return to the hotel!

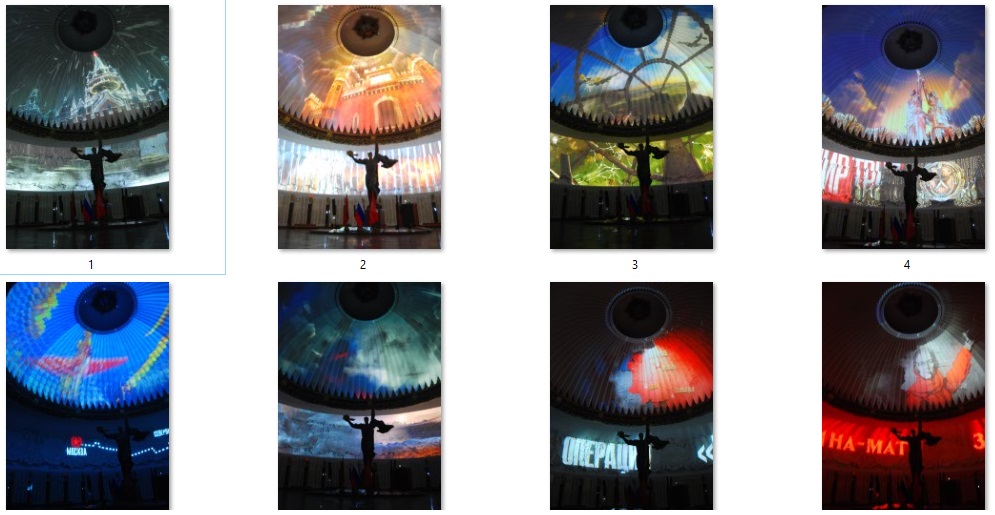

The Speaking Dome

Our guide, Miss Sin (invented name), awaited us to lead us through the museum’s halls as if she carried history in her hands, a lamp that never dims. We began under the soaring dome, where the war film unfolded like a wound rekindled: planes screaming across a trembling sky, soldiers swallowed by snow, cities rising from rubble like prayers refusing to die. I started photographing the dome, regretting the absence of my video camera, for still images could not capture the immersive force of the Russian-narrated film—but we understood it.

As the images swept us along, I felt the Nile and Volga speak the same ancient tongue: the language of loss and patience. Patricio’s breath froze in the cold air; Olga’s eyes glimmered with inherited sorrow; Sin’s silence was a reverent bow. From there, we moved to the “Hall of Memory and Sorrow,” where tears of crystal hung in eternal silence, as if grief floated in the air like light incense. Then to the “Hall of Glory,” where marble columns rose like rows of soldiers, and the bronze soldier stood triumphant yet weary, reminding us that victory carries tremors. We ascended next to the “Hall of Military Leaders,” where bronze faces stared, testing our courage, then continued through rooms where letters, diaries, and Zhukov’s worn bag breathed truth from yellowed pages.

Within the Museum’s Arteries

Around us, dioramas brought life to frozen Moscow trenches, blazing Stalingrad factories, fragile Leningrad hunger, the thunder of Kursk, fires along the Dnieper, and the weary twilight of Berlin—each scene a poem carved from suffering and resolve. We entered the lives of wartime people: a loaf measured by survival, a besieged library, a workshop echoing the heartbeat of its workers, children’s drawings glowing with hope despite all.

From the edge of the cold sunset, we wandered through the museum’s arteries like fleeing droplets of blood, where history pulsed along corridors embroidered with the murmurs of a nation enduring trial. With Sin’s calm certainty, we descended to the depths, beginning in the Hall of Historical Events, where illuminated maps opened like ancient chronicles, tracing the shifting lines of battles as if scars cracked and healed on Europe’s body. The maps lit our faces: mine echoed distant wars along the Nile, Patricio traced similarities in Latin American struggles, and Olga stood bridging two times with woven languages and loss.

Before boarding one of the wagons that transported survivors, a woman wandered nearby, seated between bins on a discarded crate, surrounded by a pile of books—saving books was like saving lives. She sat briefly, then followed the group into the wagon, where Sin asked:

Before boarding one of the wagons that transported survivors, a woman wandered nearby, seated between bins on a discarded crate, surrounded by a pile of books—saving books was like saving lives. She sat briefly, then followed the group into the wagon, where Sin asked:

“How many people can this wagon hold?”

After a visual estimate, I said, “Thirty.” For exaggeration, Patricio answered “a hundred,” which was closer to reality; fleeing the fire required packing as many as possible, standing with no rest on their grueling journey.

Hologram of the Leaders

From a glass window, we saw the Russian command room during the battle, the figures moving as holograms, as if the dead had been brought back to life:

The darkened room was crowded around a large map on the table, with senior Soviet leaders seated nearby. Joseph Stalin lifted his head, eyes gleaming with focus, and said, “The situation on the Western front is worsening. We must strengthen defenses around Moscow before the enemy approaches further.”

Georgy Zhukov smiled faintly, peering at the map of movements: “We need more tanks and heavy artillery. The troops must be ready for any counterattack. If we move quickly, we can turn the battle in our favor.”

Nikolai Podgorny approached the table and added in a calm voice: “The air units need immediate support. German aviation controls the skies in some areas, and if we do not respond, we will lose more territory.”

Vasily Skryabin sighed: “Supplying provisions and food to the front is as crucial as moving the troops. The soldiers need everything to maintain morale.”

Stalin looked at them all, then raised his hand and said firmly, “We cannot hesitate. Every decision you make must be precise. Moscow is the heart of the Soviet Union, and we will not let it fall.”

Silence fell for a moment, as everyone focused on the map, each thinking of their next moves, aware that a single mistake could cost land, time, and soldiers.

In the quiet turns of the museum, we reached the Hall of Generals, where the stern stares of the leaders carried the frost of early mornings and sleepless nights, the scent of old paper and polished metal evoking the preserved essence of strategy. Then we entered the Hall of Medals, glittering like a path of stars fallen to earth; the medals behind glass were not mere decoration but lives fused into bronze and silver: courage and sorrow cast in metal.

Heroes of Daily Life

The museum transported us to schools, hospitals, weapons factories, libraries, train stations, and rooms hiding paintings later looted by Nazi soldiers. In the Hall of the Home Front, statues of workers, teachers, and mothers embodied the silent heroism of everyday life. A dim kitchen preserved the warmth of laughter long extinguished; sewing machines stood beside factory tools, as if life itself had been woven from iron threads. Olga read a note in a diary behind glass: “The smell of bread tonight smells like victory.” Silence fell, even over Patricio.

In the Hall of Nazi Crimes, the light dimmed and silence deepened. Burned villages, mass graves, homeless children; documents, prisoners’ clothes, stripped of their names, reduced to numbers—reminding me of my novel, 31, where every protagonist is numbered. I felt the air tighten in my chest; the horror was neither Russian nor European, but purely human. Olga’s hand trembled as she translated, as if the wind swept through the pages of her soul.

Amid the horrors of war, seeing your own sons and countrymen in enemy ranks struck deeply. Sin took a pass card; a giant guard shouted at us to present papers, smiling when he saw Patricio’s alarm. I told him, “Your role forbids smiling.” Patricio found consolation speaking Spanish with a worker in the arms factory—a linguistic surprise that amazed us. Scientists can always astonish, especially if they are Russian!

Raising the Red Flags

From the darkness, we entered the Hall of Victory, where flags shouted from the ceiling and soldiers’ footsteps echoed through hidden speakers. Visitors ascended the Reichstag steps as if climbing from darkness into dawn. We raised the red flags, reaching then the liberated cities of Europe; freedom was not for Russia alone. The Red Army had contributed to freeing European capitals, represented in the museum, which houses over 830,000 artifacts according to its official site, with exhibition halls in the main building covering over 14,000 square meters.

One puzzle was the forbidden radio, hidden during the occupation so citizens could not listen. Sin shone a lamp, revealing the radio concealed behind a painting. The museum does not merely display memory—it is lived; a monumental project preserving the memory of millions of martyrs and the ultimate victory over Nazi Germany.

The numbers… they are shocking, a scream in the night’s silence. From twenty to twenty-seven million Soviet souls were swept away in the war’s vortex—soldiers and civilians, men, women, and children—almost a quarter of the entire population. Cities were leveled, factories vanished in smoke and ash, families erased as if they had never existed.

Leningrad endured a siege for nine hundred days; Stalingrad became a human grinder of blood and steel; Moscow itself nearly fell, on the edge of annihilation.

Yet this war was not distant, not on unknown borders. It unfolded in their gardens, among their fields, in the corridors of their homes. It planted pain in every corner, making each family a story: of loss, sacrifice, hunger, or death defending the motherland.

A collective suffering, yes, but one that created a shared memory, a bond transcending generations.

Thus, Victory Day on May 9 is more than a holiday; it is sacred—a day to weep and celebrate together, to remember those who gave everything for the survival of all.

Glory of Russia, Glory of Europe

Walking through the halls of the Victory Museum, one feels that history is not merely an idea—it is the air you breathe. Every artifact, every diorama, every name engraved in marble is a direct thread to the colossal struggle, a testimony that the resilience of these people ensured not only the survival of their nation but also of a large part of Europe.

We passed through the art gallery and special exhibitions showcasing works by Soviet war artists, depicting scenes from the front lines, heroism of soldiers, and civilian endurance. Temporary exhibitions are also held, highlighting individual heroes or lesser-known campaigns, keeping the visitor’s experience fresh and dynamic. After the visit, I sat to write a telegram to the soldiers on the front, wishing them endurance, and Olga placed the message in the mailbox. This has been a tradition for eighty years: citizens send letters to soldiers, no matter the recipient; the important thing is the message telling them to hold on.

Perhaps the most symbolic scenes were the dioramas of the Berlin occupation: April–May 1945, depicting the final violent assault on the German capital, with street fighting, Soviet tanks advancing through barricades, and infantry crawling among the ruins of Berlin. The focal point is often the Reichstag building, illustrating the wide struggle for control over the city. It is a powerful visual embodiment of the end of years of brutal combat and the moment of ultimate victory. The raising of the Soviet flag on the Reichstag captures the chaos and excitement of the final hours of the battle, with room-to-room combat, the building’s destruction under artillery fire, and the symbolic act of hoisting the flag, announcing the end of the war in Europe. It is a moment rich with symbolism and national pride, portrayed magnificently.

In Front of the Victory Monument

History, on this scale, is not merely dates and battles—it is humanity itself: its suffering, courage, and unbreakable spirit, transforming ashes into hope and tears into resilience, reminding us that freedom comes at a high price and that remembrance is the flame that keeps the fire alive.

When we emerged into the Moscow night, I could not resist taking a commemorative photo in front of the colossal Victory Monument, soaring 141.8 meters into the sky. This number is not random; it symbolizes the 1,418 days and nights of the Great Patriotic War. At its summit stands the bronze goddess Nike, the ancient Greek goddess of Victory, holding a wreath, flanked by two angels blowing trumpets. At the base, a magnificent statue of Saint George slaying the dragon (symbolizing the triumph of good over evil, or specifically, Russia over Nazism) completes the powerful image. Seeing this monument rising above Moscow is truly an inspiring sight, preparing the visitor for a full experience imbued with grandeur.

On Poklonnaya Hill, or the “Bow Hill,” with its panoramic views of Moscow, travelers bow to the city upon arrival or departure. I stood where Napoleon stood in 1812, awaiting keys to Moscow that never arrived. It was a place charged with anticipation and historical significance, making it the perfect—and almost fated—site for this decisive memorial complex.

Our visit to the museum lasted more than an hour and a quarter, yet I felt as if I had lived a thousand days and a day, under skies where wars raged, with an unforgettable history and humans who resisted.

Winter was taking its first steps. There, in the harsh evening cold, I carried with me the certainty of the museum: that the human spirit, no matter how heavy the darkness, always knows how to light a candle.