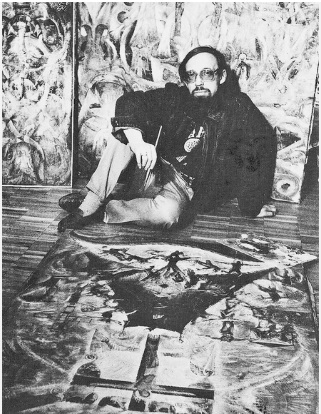

In Moscow, at the Gallery on Chistye Prudy, an extraordinary exhibition titled “The Path of White Clouds” is on display. This is the largest solo exhibition of 100 works by artist Sergei Potapov, who is currently better known in the West than in Russia. The exhibition is dedicated to the artist’s 77th birthday and serves as a retrospective of his many years of creative work.

A Life Marked by Struggle

Sergei Potapov‘s fate has been quite dramatic, much like that of many nonconformist artists of the 1970s and 1980s. His journey included everything that a talented artist who refused to conform to Socialist Realism would face: the KGB shutting down his exhibitions, expulsion from the Moscow Union of Artists (MOSKh), financial hardship, and ultimately, an internal exile—painting in solitude, with no hope of recognition.

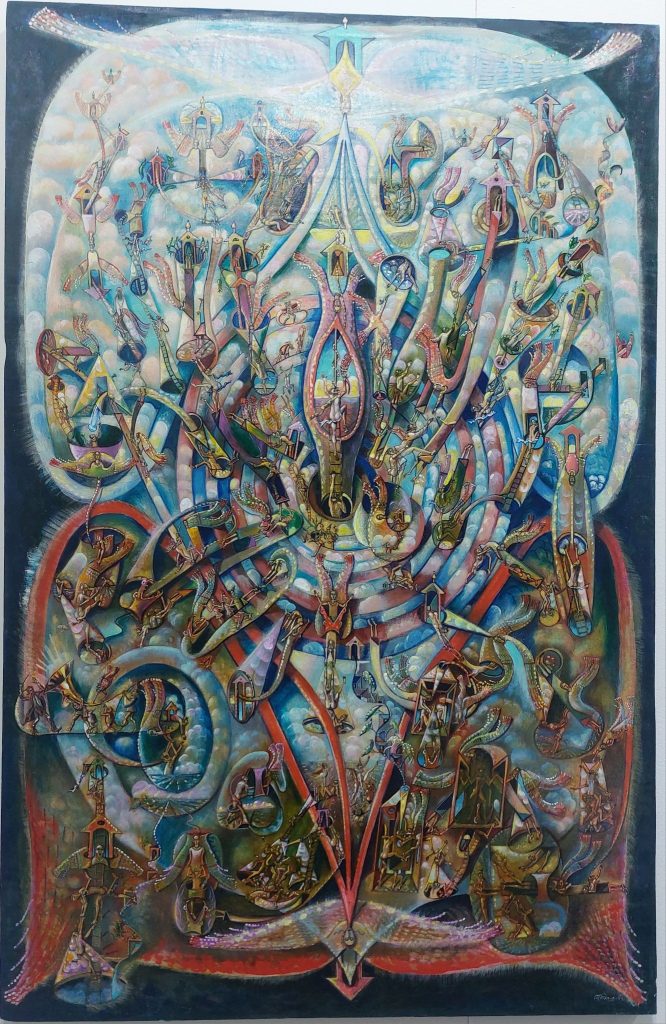

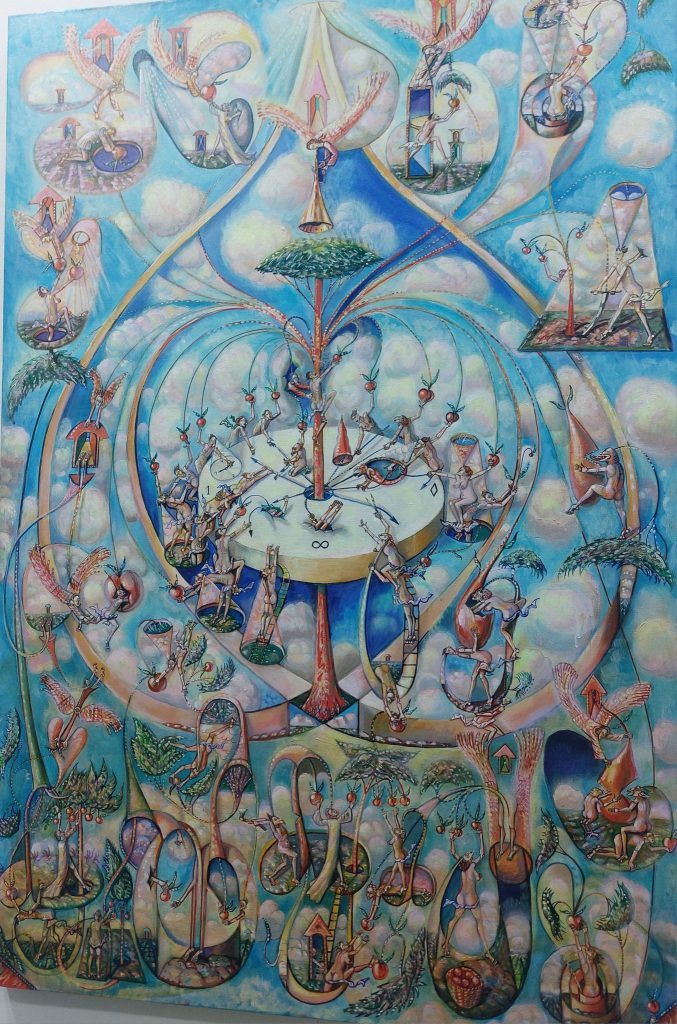

At times, Sergei Potapov’s situation was so dire that he could not afford canvases. Like the famous Georgian painter Niko Pirosmani, he turned to painting on oilcloth, which later became highly valued by collectors. His fortunes changed with Perestroika, which gave him the opportunity to exhibit not only in Russia but also abroad. His talent was finally recognized, and in the West, he became known as the “Russian Bosch.”

Artistic Roots and Influences

Sergei Potapov was born in Riga in 1947 to an architect’s family. In 1970, he graduated from the Moscow School of Industrial Art (formerly the Stroganov Academy), where he studied under Professor Heinrich Ludwig—a major theorist and practitioner of avant-garde architecture, an expert in ancient languages and philosophies.

Ludwig, a figure compared to Leonardo da Vinci, was repressed in 1937, imprisoned until 1956, and survived under harsh conditions thanks to his esoteric and medical knowledge. He was spared because he treated Soviet labor camp officials and their wives using Tibetan medicine. Upon release, Ludwig taught a course titled “Symbolism in World Culture” at the Stroganov Academy—a course that was unlike anything else at the time.

His lectures combined linguistics, ancient and medieval history, architecture, world mythologies, early Kabbalah, astrology, ornament symbolism, phallic cults, labyrinth types, and scientific anomalies. For students raised on Soviet street folklore, unfamiliar with the Bible—let alone Plato, Herodotus, or Vasari—this course was a revelation. Few attended, but among them was Sergei Potapov.

Ludwig’s teachings deeply influenced Potapov, leading him to develop his own symbolic language in art, culminating in the 1970s in a style he called Post-Symbolism.

Encounters and Artistic Evolution

In January 1975, Potapov met Svyatoslav Roerich as part of the Moscow Agni Yoga group. When Sergei Potapov asked Roerich how to find his artistic path, Roerich advised:

“Develop and refine what you have already grasped and bring it to its logical conclusion. If done honestly, the next step will be revealed to you.”

Potapov’s initial inspiration for painting on oilcloth came from Pirosmani, while his conceptual direction stemmed from Pavel Filonov’s manifesto, which he discovered in a 1967 Czech art journal, Vitvarne Umeny. This shaped his idea of scanning different planes of existence through a symbolic visual language.

Potapov’s art moved from naive symbolic interpretations of emotions—dreams, joy, anxiety—toward mental constructs expressed through conceptual-meditative vision.

A Nonconformist’s Struggle

A Nonconformist’s Struggle

During the 1970s, Potapov joined the nonconformist art movement, exhibiting in unofficial shows, including the legendary Gallery on Malaya Gruzinskaya 28. His artistic journey was one of seeking meaning, building his own painterly system, and exploring self-knowledge through art. In his cosmic mandalas and astral landscapes, he sought to depict all levels of human consciousness and existence within a single space.

In March 1980, Potapov held his first solo exhibition in Moscow at the Kurchatov House of Culture, but after three days, it was shut down by Soviet authorities due to alleged political subtext and mysticism.

By 1981, he was expelled from the Committee of Graphic Artists, and in 1982, he was denied membership in the Moscow Union of Artists, a status he only obtained in 1988 during Perestroika.

That same period saw his works exhibited in Washington, D.C., at Georgetown University, as part of the Mikhail Makarenko Collection of Nonconformist Art. His works were displayed alongside Pavel Filonov and Dmitry Grinevich, affirming his place as a follower of Filonov.

Potapov’s paintings were also acquired by Norton Dodge, the foremost collector of Soviet nonconformist art and the man who coined the term “Soviet Nonconformism.” Dodge not only recognized the political resistance in this movement but also its unique artistic significance within 20th-century art history.

Themes and Artistic Philosophy

Sergei Potapov is a recipient of multiple international awards. His Post-Symbolist works explore the clash between physical and metaphysical reality, the dialectic of Good and Evil, and the soul’s ascent toward transcendence.

His artistic system is based on his personal visionary experiences and improvisation. For years, he has studied philosophy, art history, and Eastern practices, working as a methodologist in cultural theory and design.

Art historian Elena Vyunik analyzes his work:

“Potapov’s intellectual approach is precisely what makes his art difficult for art historians to categorize. Experts, accustomed to neatly labeling styles and schools, are puzzled—where does he belong? Superficially, his work resembles Filonov and Bosch, but such comparisons obscure a deeper understanding of his paintings.”

At the exhibition’s opening, Potapov stated:

“For me, a painting is a visual meditation, a window into the universe with its own perspective and vanishing point. It is always a model of the world, a path of meditation requiring the viewer’s attention, ability to observe, wonder, and think. The method of painting is based on a personal language of symbols and metaphors—a translation of the multidimensional world onto a two-dimensional canvas. To me, a symbol is both a way to overcome time and a bridge between different eras.”

Exhibition Details

The exhibition is open until August 18 at the Gallery on Chistye Prudy, Chistoprudny Boulevard, 5.

– Olga Medvedko, Cultural Studies Expert

A Nonconformist’s Struggle

A Nonconformist’s Struggle