Ethnic Cinema … Halima’s Path

By: Fatima Al-Zahra Hassan, Writer and TV Director, Egypt, CAJ International Magazine

Cinema in the Balkan region gained widespread global recognition after the Bosnian-born, Serbian director Emir Kusturica (born in 1954) won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1985 for his film When Father Was Away on Business and again in 1995 for his film Underground.

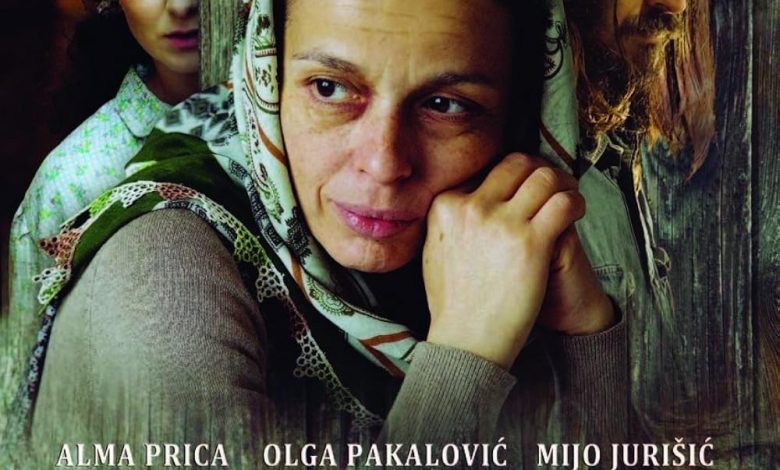

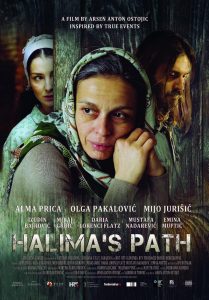

The Croatian film Halima’s Path, directed by Arsen Anton Ostojić, was screened under the “Human Rights” section at the 35th Cairo International Film Festival in 2012. It also won the Grand Prize at the 19th Tetouan Mediterranean Film Festival, where the jury awarded Best Actress to Croatian actress Alma Prica for her role in the film.

The film can primarily be classified as a social-humanitarian drama, tackling a complex and unfamiliar topic, particularly for Arab and Muslim societies, where people coexist peacefully with those of different religions and sects. The central conflict raises a question that challenges traditional norms: How can a Muslim woman marry a Christian man, live with him, and have children together?

This is considered a grave and forbidden act, one that would render the woman an outcast from her religion. Initially, I did not sympathize with the issue because, from a fundamental standpoint, it is unacceptable. However, the film, produced in Croatia, presents its narrative against the backdrop of the ethnic cleansing campaigns carried out by the Serbs against Bosnian Muslims during the Bosnian War (1992–1995), a conflict that resulted in the death of 100,000 people, the majority of whom were Muslim.

The film’s events are based on a true story, as stated in its introduction. It takes place in 1977, in a village in western Bosnia and Herzegovina during the time of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, which consisted of six republics: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro, Macedonia, and Slovenia. This union was established by Josip Broz Tito after the country was liberated from German occupation in 1945. Tito remained in power until his death in 1980, which marked the beginning of the dissolution of Yugoslavia.

Halima’s Path

In 1977, a young Muslim woman named Safiya seeks refuge at the home of her aunt, Halima, pleading for protection from her father, Abdu, who would kill her if he found out she was two months pregnant out of wedlock. However, the real scandal is not just that she is pregnant—but that the father of her child is a Christian Serbian man named Slavo!

When her father learns about the disgrace, he beats her mercilessly. At that moment, Slavo enters the yard, strikes Safiya’s father on the head to stop the assault, and then flees when Safiya’s brother attacks him. Her brother disowns her and expels her from their home, forcing her to take shelter with her aunt, Halima.

The film then jumps to the year 2000, 23 years later, after the Bosnian War and the mass genocide of Bosnian Muslims by the Serbian military and civilians. The world witnessed these horrors without meaningful intervention. Yet, rather than relying on graphic violence or bloodshed, the director recalls these massacres and war crimes in a restrained, emotionally poignant manner.

Halima constantly remembers a painful scene: she is seen begging Serbian soldiers to spare the lives of her son, Mirza, and her husband, Salko. However, the soldiers show no mercy and take them away in trucks, along with other men and young boys, to be executed. Years later, Halima searches for her husband’s remains using a DNA sample from her husband’s brother, which allows her to locate his body. However, she is unable to find her son, Mirza. The tragic reason? Mirza is not her biological son—but rather Safiya’s illegitimate child, whom she had entrusted to Halima to avoid disgrace, claiming that the baby had died at birth.

Safiya had eloped with Slavo in 1979 when he returned from Germany. They settled in a Serbian-controlled region, where she gave birth to three daughters. Now, 21 years later, Halima seeks out Safiya, urging her to provide a DNA sample so that the UN team can confirm Mirza’s identity, as thousands of mass graves of executed Bosnian Muslims have been uncovered.

A devastating scene unfolds in the film: skeletal remains are meticulously cataloged in a massive forensic laboratory, with each pile assigned a number before being returned to families for proper burial following DNA analysis.

Meanwhile, Safiya’s life is in turmoil—her husband, Slavo, has become an alcoholic and suffers from severe psychological distress in the aftermath of the war. When Halima asks her to provide a DNA sample for the UN team, Safiya refuses, fearing that Slavo would kill her if he discovered their son was still alive.

The Climax

At this moment, Halima sees a photograph of Slavo for the first time and is shocked. She suddenly recalls the day Serbian soldiers took her husband and son—one of them had spoken to her and promised that they would return. But they never did… because they were murdered.

That soldier was none other than Slavo.

Halima collapses in horror upon realizing that Slavo, Safiya’s husband, was one of the Serbian soldiers who executed her son, Mirza, without even knowing it was his own child.

Returning home in silence, Halima does not confront Safiya. Meanwhile, Safiya and Slavo’s marriage deteriorates further, as his drinking worsens. Seeking solace, Safiya visits Halima, who then reveals the painful truth: Slavo had killed his own son, Mirza, during the ethnic cleansing campaigns. Halima hands her a photo of Mirza at 16, taken shortly before his father unknowingly murdered him while serving in the Serbian military.

Finally, after Halima provides the DNA sample confirming Mirza’s identity, Safiya confronts Slavo with the truth—he had killed his own son. Unable to bear the guilt, Slavo commits suicide and is buried in a Serbian Orthodox cemetery, while Mirza is buried in a Muslim cemetery.

Safiya’s father, Abdu, attends Mirza’s funeral, accepting his grandson’s fate after years of rejection. Halima places on Mirza’s grave a jacket she had lovingly sewn for him during her long search for his remains.

As the film ends, Abdu gazes at his three granddaughters, now living with their mother, Safiya, in the Muslim side of the city. He appears lost in thought, contemplating a future free from the sectarian and ethnic strife that had caused so much bloodshed, hatred, and devastation throughout history.

Ethnic Cinema … Halima’s Path

By: Fatima Al-Zahra Hassan, Writer and TV Director, Egypt, CAJ International Magazine | March Edition

Ethnic Cinema … Halima’s Path

Ethnic Cinema … Halima’s Path