As Heraclitus said centuries ago, “You cannot step into the same river twice.” Similarly, theater remains in a state of perpetual renewal, evolving with each passing second and moment. This is why “theater is destined for immortality—it is born and dies in the same instant, only to be reborn again.”

The constant renewal of theater is rooted in the “theater laboratory,” even before this term was formally coined. The theater laboratory is intrinsically linked to experimentation, which is necessarily intertwined with modernity, as stated in every theatrical dictionary. There is no doubt that the experimentation conducted in theatrical laboratories consists of attempts to introduce new creative innovations at all levels of the fourth art. Over time, these innovations inevitably become part of the classical past, and so the cycle continues.

The evolution of the fourth art through laboratory experiments and modernist exploration has significantly amplified the role of visual arts within theater. The Cubist school, in particular, has played a tangible role in this regard. The history of theatrical laboratories that shaped these concepts is well documented in every study on the fourth art—to the extent that one might say this history is readily available to anyone who seeks it. Who among us does not know André Antoine, Konstantin Stanislavski, Max Reinhardt, Edward Gordon Craig, and his counterpart Louise Lara, as well as Jerzy Grotowski, to name just a few in chronological order?

However, the history of theatrical laboratories in the Arab world remains relatively obscure, known only to specialists. It is worth mentioning the contributions of pioneering figures who fought for the development of theater. Among the most influential was the late Abdel Rahman Arnous from Egypt, who left behind generations of creative minds in Egypt and Jordan, particularly from Yarmouk University, many of whom are now prominent names, such as director Hakeem Harb. Meanwhile, in Egypt, the great director Samir Al-Asfoury was laying the foundation for new generations in Tali’a Theater, producing renowned directors such as Mohsen Helmy, Essam El-Sayed, Nasser Abdel Monem, Intisar Abdel Fattah, Hassan El-Wazir, Ahmed Hani El-Mehy, Mohamed El-Khouli, Sobhi Youssef, and others. From Iraq, we have the esteemed Dr. Salah Al-Qasab, may he live long, and from Tunisia, Tawfiq Jebali, Fadhel Jaibi, the late Ezzedine Gannoun, and Raja Ben Ammar, as well as her longtime companion Moncef Souaïm, may he have a long life.

In the Tunisian context, especially in experimental theater and dramatic writing, we must mention the great writer Ezzedine Madani, who sought to reinvent heritage through innovative forms. From Morocco, the pioneering works of the late Tayeb Saddiki and younger figures like Bousselham Daif emerged. In the Gulf, significant experimental contributions came from Awal Theater Group, and directors like Abdullah Al-Saadawi, Khalifa Al-Arefi, Abdullah Al-Munai, Mohamed Al-Ameri (UAE), and Suleiman Al-Bassam (Kuwait). Despite the prominence of these names, it can still be said that the tradition of theater laboratories has not been as firmly established in the Arab world as it has in the West and Asia.

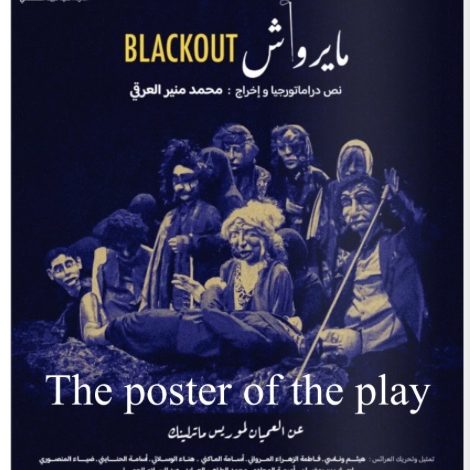

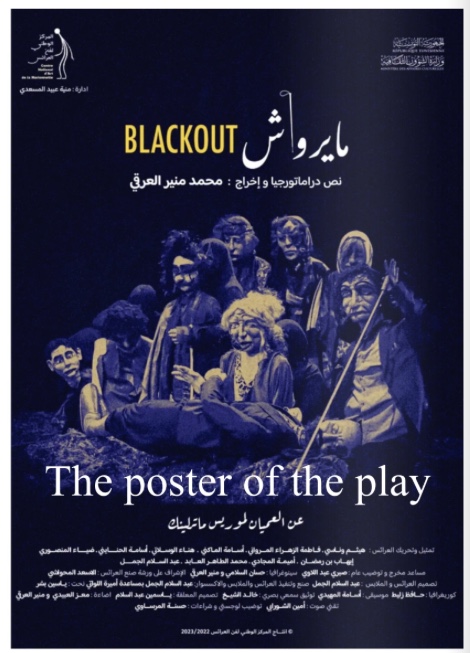

This introduction was necessary to set the stage for a remarkable theatrical work on multiple aesthetic levels—the production of “Ma Yaraouch” (“They Do Not See”), directed by the esteemed Tunisian director Mohamed Monir Al-Arki. The play is based on “The Blind” by the Belgian playwright, poet, and journalist Maurice Maeterlinck, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1911.

The writings of Maurice Maeterlinck, also known as Count Maeterlinck, contain profound mystical and spiritual elements, inspiring those who can immerse themselves in his mythological perspectives on reality. His works often take reality as a foundation but reshape and reinvent it, sometimes creating independent artistic visions that diverge significantly from their original sources.

The essence of theater laboratory work revolves around the director, who orchestrates the theatrical elements within the designated dramatic space. Naturally, the most vital of these elements is the actor, who embodies the roles. In a full theatrical production (as opposed to mere exercises), the text serves as the core that unites all elements—one might say it carries them on its back.

In the puppet theater production for adults, “Ma Yaraouch”, the intricate role of director Mohamed Monir Al-Arki is evident. While no production can exist without a director to shape and organize it, the dramaturg is the foundation upon which the entire performance is built. In this case, Al-Iraqi himself undertook this role, effectively transforming Maeterlinck’s The Blind into a work with its own unique identity—perhaps even reshaping its abstract philosophical concepts into something entirely distinct.

“Ma Yaraouch”: In the Lodge or the Cave?

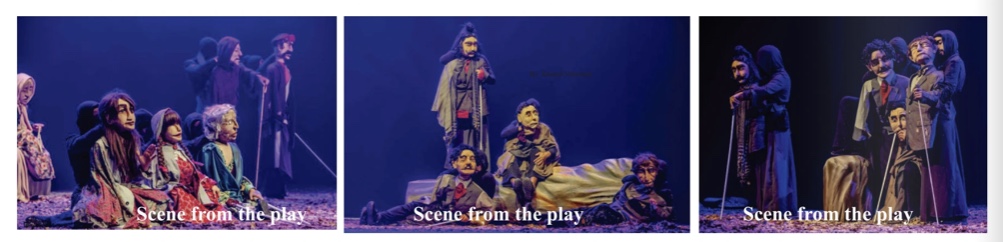

The blind characters in Monir Al-Arki’s “Ma Yaraouch” (“They Do Not See”) live in a lodge (tekyeh) with their Sheikh, Al-Hadi. However, the setting immediately evokes Plato’s Cave, prompting the audience to question whether these blind individuals are living in the realm of reality or the realm of shadows. And if they do dwell in reality, is it an absolute truth or a relative one, shifting depending on each individual’s perception? Even when these blind characters leave the lodge and venture into the island—surrounded by the sound of the sea, natural effects, and dry leaves—they struggle to perceive and understand the world around them. Their visions differ to such an extent that the audience is once again drawn into the existential dilemma of truth versus illusion—a concept as layered and intricate as ever.

The Dead Controlling the Living

As the great Abbas Mahmoud Al-Aqqad once said, “There are dead buried in shrines who still control the living.” How could it be otherwise when the shrine’s inhabitant—a lifeless body—is succeeded by a Sheikh who claims wisdom and divine knowledge, yet is, in reality, spiritually dead and emotionally numb? This creates an additional realm of shadows—layered upon those of the cave or the lodge—through the myths that he perpetuates to maintain control over those who have chosen to surrender their will. Even if they manage to escape their prison, they remain trapped in an illusionary world where their perspectives are not only distorted about truth itself but even within the very realm of shadows they inhabit.

A powerful illustration of this is the scene of the blind, violated young woman, which serves as a profound metaphor for the very ideas discussed above. These blind captives—imprisoned by their physical blindness, their submissiveness, oppression, society, and mythologies—are unable to break free from the world of shadows. After all, their Sheikh, Al-Hadi, can seemingly transport them to the holy lands by the power of his so-called miracles. The ultimate shock for these prisoners comes when they realize they have spent their lives following, or rather worshipping, a dead Sheikh or a false god.

“We Are Slain by the Enemy Within Us”

The puppets, masterfully manipulated by the actors, were crafted with precision and finesse, serving as an artistic enhancement to the director’s ingenious use of the fourth wall. This theatrical technique is reminiscent of Bertolt Brecht and his followers. By integrating puppet theater, creating multi-layered depth in physical performances, and drawing upon the poetic sensibility of Maeterlinck’s original text, dramaturg Monir Al-Arki immerses the audience in an eternal dramatic conflict between truth and illusion.

The dynamic between the actor and the puppet oscillates between harmony and conflict, leading the perceptive viewer to hear the echo of Mudhafar Al-Nawab’s haunting lament:

“We are slain by betrayal… we are slain by betrayal… we are slain by the enemy within us.”

It is a theatrical representation of the schizophrenia that defines the lived reality of this region—an existential crisis where truth itself is perpetually contested.

The Symbolism of Names, Spaces, and Their Impact

Dramaturg Monir Al-Iraqi cleverly employs symbolic names for his characters, immediately evoking the Naguib Mahfouzian style of layering meanings through nomenclature. This extends to the setting—the lodge (tekyeh)—recalling the lodge in Naguib Mahfouz’s “The Thief and the Dogs,” where the protagonist Saeed Mahran sought refuge, only to meet a nihilistic fate—one eerily similar to that of the blind characters in “Ma Yaraouch.”

With the actor and puppet, the characters and audience, the lines between reality and performance blur. After breaking the illusion, a profound question remains:

Who is truly blind, and who can actually see?

Who among them is the one that “does not see” (Ma Yaraouch)?

A Theatrical Triumph

Director Monir Al-Arki made a brilliant choice in staging the play at the Hammamet Theater, where the space itself enriched the performance. The extraordinary integration of location and scenography elevated the production on all levels.

“Ma Yaraouch” is a spectacle that demands multiple viewings and analytical readings—a 115-minute journey of genuine artistic pleasure.

A Well-Deserved Salute to the Cast & Crew

Acting & Puppeteering: Haitham Wanasi, Fatma Zahra Marouani, Oussama Makni, Hanaa Weslati, Oussama Hanaïni, Diaa Mansouri, Ihab Ben Ramadan, Omaima Mejdi, Mohamed Taher Al-Abed, Abdel Salam Al-Jammal, Al-Asaad Al-Mahwashi.

Puppet Workshop Supervision: Al-Asaad Al-Mahwashi, Puppet Design, Costumes & Crafting: Abdel Salam Al-Jammal, Sculpting: Yassine Bechar, Choreography: Hafez Zlit, Music Composition & Arrangement: Oussama Mehdi, Puppet & Accessories, Execution: Amira Al-Louati, Lighting: Moez Al-Abidi, Mohamed Monir Al-Arki, Scenography: Hassan Al-Salami, Mohamed Monir Al-Arki, Dramaturgy & Direction: Mohamed Monir Al-Arki.