By Filippomaria Pontani

In 1878, at the mouth of the River Tyne in South Shields near Newcastle (just a few kilometers north of The Old Oak pub, which in Ken Loach’s film of the same name becomes the setting for the cultural clash between the dwindling inhabitants of a declining mining suburb and a group of Syrian refugees in 2013), an ancient funerary plaque from the third century AD was discovered. It bore an inscription in a mixture of Latin and Palmyrene Aramaic, commemorating a man who had been freed from slavery.

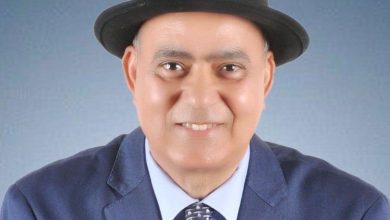

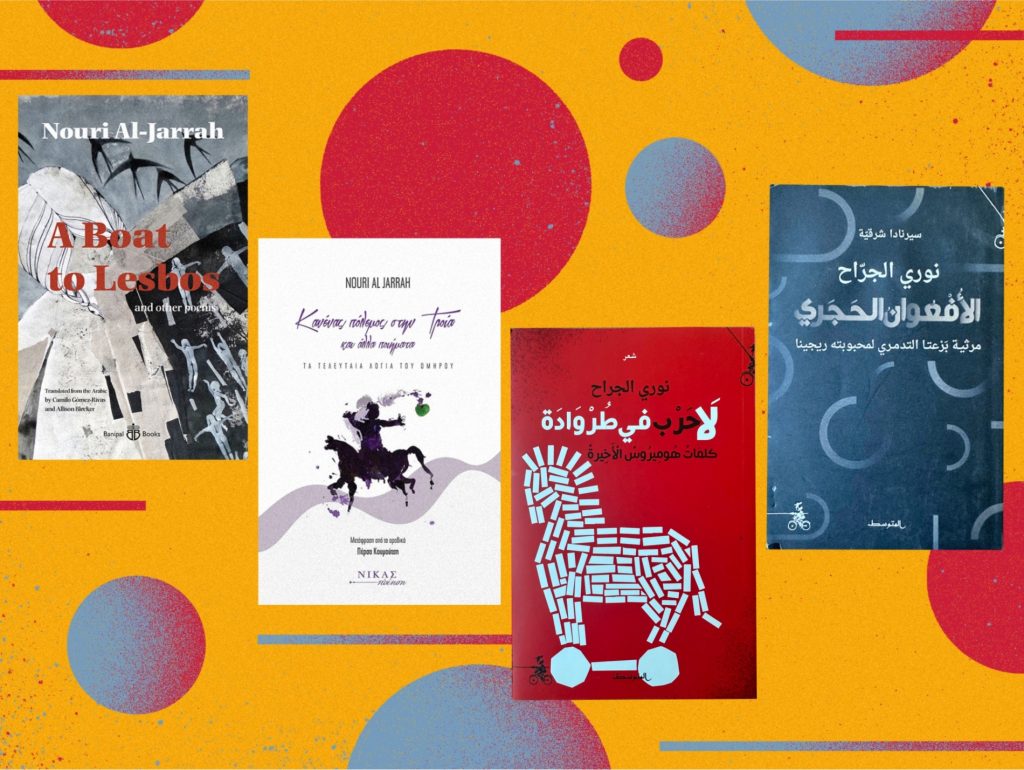

This story of intercultural love would have fascinated a poet: it was a Damascus-born poet living in London, Nouri Al-Jarrah, who took up the theme in his reflections on the relationship between Syria and the Mediterranean. In his work A Boat for Lesbos (L’Arcolaio, 2018), he revisits the idea of Syrians as people born not on boats, but in the foam of the sea—pure gold transformed, fused, and infused with a deep fragrance.

Two years later, in Exodus from the Abyss of the Mediterranean (Le Monnier, 2023), the exiled Al-Jarrah returns to Italy with The Stone Serpent, a delicate poetic collection translated by Gassid Mohammed.

In his Elegy for Regina, the exiled poet Barate retraces his life: his perilous arrival on English shores, the archers of Palmyra guarding Hadrian’s Wall, the melting pot of people and goods in the heart of Britain, the memories of Queen Boudicca’s anti-Roman revolt, and the establishment of a Syrian dynasty on the imperial throne (Septimius Severus and Julia Domna). All of this unfolds against the backdrop of his love for Regina, tragically cut short by death. Here, the dark-skinned Middle Eastern foreigner and the fair native woman in chains reverse the weight of civilization, while nostalgia, fog, and humanity take center stage.

The gods shift and transform—Atargatis becomes Ishtar, then Aphrodite, Zeus turns to Baal, then to Odin—in a syncretism that today’s Europe seems increasingly unwilling to acknowledge.

In the appendix, poems like The Elegy of Antinous and The Edict of Caracalla echo the spirit of Cavafy, listing the various nations present and the unease of “barbarian” citizens before symbols of power. However, Al-Jarrah’s refined historical references are lighter than the grandiose allusions of Adonis or Nizar Qabbani. His work is softened by notes of tender nostalgia, a memory both personal and collective.

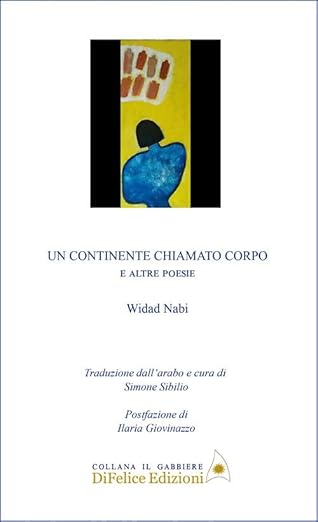

Another exile, another voice from Syria: Widad Nabi, a young Kurdish woman from Kobane, fled to Germany in 2015 after a dramatic escape.

TWO POEMS

Nouri Al-Jarrah, from Elegy of Barate to His Beloved Regina

The cloud-bearer guided my steps

from the blue of summer to the dark winter.

The daughters of dew, the maidens of mist,

who once laid Baal in my fields,

have now left me here, disoriented.

The sky prepared for the first rains,

the stars made the artemisia bloom,

filling the air with its fragrance.

I led you to the source of the two rivers,

made you wander in the sun of my days.

Why did you accept my vows,

only to later allow the earth

to take from me the last thing

a stranger can ever possess in this world?

Widad Nabi, from Scenes of Imperfect Happiness

I will always sound like a sad woman

I will always sound like a sad woman

As I race like an untamed horse toward love

Clutching my empty hands.

A sad woman

who weaves out of nothing

the omens of a house

built from an ancient lament.

I will always sound like a sad woman,

no matter how my photographs hanging on the walls

may appear to be those of a woman

from a happy land.

A woman in a colorful dress

worn for twenty years,

and a war from whose pockets

spills the salt of the Aegean—

That salt that settled in her body

when she boarded the boats of death.

That salt embedded in the gaze

of her empty eyes—

The gaze of someone

who gave everything to death

just to survive.

Widad Nabi fled the dark abyss of war but refuses to be confined by the stereotype of the “refugee poet,” a label often used to marginalize literary work of this nature. She chooses to write in her fragmented, foreign-acquired German, seeking to escape easy classifications. Her poetry, infused with the scents of a lost homeland—the city, the minaret, the Kurdish landscape—transcends mere nostalgia.

As Aleppo and Berlin merge in her consciousness, and her last name (“prophet” in Arabic) evokes an interplay between “kiss” (qubla) and “prayer direction” (qibla), Nabi embraces a direct and determined style, avoiding obscurity. Her work, though deeply rooted in personal trauma, aspires to a universal dimension.

Bibliographic Details

Nouri Al-Jarrah

Translated by Gassid Mohammed

USA, 104 pages, $14

Widad Nabi

Edited by Simone Sibilio

Di Felice, 216 pages, $16.15