Life is wise; living is genius. The moment you begin your journey through its darkness, it sets traps with one hand and lifts lanterns with the other. All you can do is stumble, rise, and learn to distinguish misguidance from clarity, shadow from light. I begin with this reflection to say: Ashraf Aboul-Yazid was one of my first lanterns—he lifted me from a fall and lit my path until I stood and arrived.

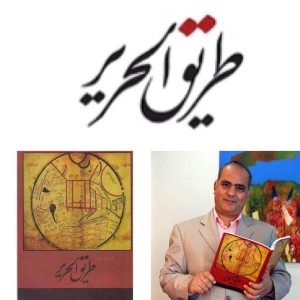

The Egyptian storyteller, as I love to call him, was the first “Google” I ever knew. A poet with five collections and a novelist with three published novels, he has authored numerous books in children’s literature and visual arts criticism. He is also a painter, translator, graphic designer, and, dare I say, a journalist to the bone. Aboul-Yazid is considered among the most prominent contemporary Arab travel writers. Above all, he’s a witty craftsman of humor—his quips could make the heavens laugh.

He writes, presents, and directs his own TV program, The Other, where he meets prominent figures from non-Arab cultures. In its two seasons, it has featured 60 episodes. He has published over 20 books and contributed chapters to many others. His works have been translated into English, Italian, Spanish, Persian, Turkish, Korean, Russian, and Swedish. He is editor-in-chief of AsiaN Newspaper and MagazineN, issued by the Asia Journalists Association, and remains one of the cornerstones of Kuwait’s iconic Al Arabi magazine.

How do you introduce someone so richly layered? He reflects:

“Perhaps I sought the answer before you asked. Self-definition always risks becoming self-praise, yet some descriptions are granted by others, and some you grant yourself. You can’t call prose poetry when it is not, nor name someone a poet who isn’t. I prefer to be called a storyteller—a term that contains poetry, history, and narration. I am, at heart, a poet and novelist. The rest exists in the margins, telling and being told. As for painting—it’s a love long postponed. I dream of days when I wake only to reach for brush and color. For now, I paint for my wife and children. One day, I’ll paint for the world.

I don’t consider myself a translator; I merely share voices I love, works I want to resonate further. So while my translations are few, they reflect my passion—like my translation of Salvador Dalí’s memoir, born of love for the art and literature it embodies.”

I met Ashraf for the first time in Muscat, Oman. He happened to be my neighbor. I often saw him walking to work, carrying with him the weight of lines and books, visibly absorbed in the intellectual concerns of his time. He would pass quietly, without pretense or pomp, en route to his creative destiny. He laughed often and greeted everyone, memorizing your height, your shoe size, your shirt color, your scent—without ever once looking directly at you.

He says:

“A human is a system of connected vessels. Don’t think you pour your feelings into a void, whether you’re writing about singing birds or defiant souls or raging tyrannies—everything overflows into everything else. What you silence here will betray you elsewhere. I care not for quantity but for quality. Some are known for a single gem; others fill volumes that pave history’s path, yet their names go unnoticed. Without inflated eloquence, I take the rare ones as my models. I do not envy the prolific—for I may search through a ton of oysters and never find a pearl.”

All this, and still Ashraf claims not to envy the prolific? I’ll let that slide, albeit grudgingly, and knock on wood as I ask him about his heroes and icons—who shaped his awareness, intellectually and emotionally?

“In each stage of life, we had our heroes. In childhood, they were all painters—from comic strip artists to Orientalist portraitists with their captivating palette. There were adventurers too, from James Bond to the characters of Alfred Hitchcock and Agatha Christie. Later, we found ourselves enchanted by letters—by the literature of Tawfiq al-Hakim, Yahya Haqqi, Naguib Mahfouz, or the writings of Mohamed Hassanein Heikal, Tharwat Okasha, Mohieddin Ellabbad. The poetry of Amal Dunqul and Salah Abdel Sabour left its marks as well.

Today, I find myself charmed and amused by the witty commentaries of today’s youth—those who pen daily columns, rising and falling in brilliance like tides. But sometimes, just one novel, one poem, one book—on science, art, or economics—can become my greatest nourishment.”

His book The Silk Road, which documents 374 cities, reveals his insatiable passion for knowledge and the way he reshapes places, reinventing them in stunning new images. I asked him about his relationship with places—what does he wish to say through them, and what about Benha, his beautiful hometown in Egypt?

His book The Silk Road, which documents 374 cities, reveals his insatiable passion for knowledge and the way he reshapes places, reinventing them in stunning new images. I asked him about his relationship with places—what does he wish to say through them, and what about Benha, his beautiful hometown in Egypt?

“I have a thousand and one homes—not in verse, but in wood and stone, glass and hair. Homes that ignite nostalgia each time their images flash by.

We leave fragments of our souls in every place we step into or feel deeply. That’s why places live inside us. A traveler like me bonds quickly with vast spaces, always feeling I’m returning rather than arriving. There is no disconnection between a place and its people. In every city I visited, I have family—both humble and noble—whose smiles erase the distances from our last meeting. My friendships endure.

Banha distilled the world for me—it had the Nile, green fields, train tracks, ancient bridges, and the innocence of youth. Yet travel made me spend more days in South Korea than in Banha, especially after I moved to Cairo over a decade ago. Still, Banha lives on in my poems—it’s where my large family resides.”

As for me, I remain haunted by the challenge of writing for children in this hyper-visual, technological era. Is the book still meaningful to today’s generation? How did Ashraf begin his journey in children’s literature?

“As a boy, I’d go to a typist who’d type out my stories, page by page. I’d staple them together and draw in the margins—those were my first books. Around that same time, I was also telling my younger siblings stories I invented, like Mrs. Kalbaz, a semi-villainous, plump woman.

That was the seed of my children’s writing. Later, I began working on more structured projects—writing poems that never talk down to young readers, drawn from daily life. For example, I wrote about migratory birds returning home, just to comfort my daughter, whose friend had left school.

Children’s literature is an essential part of shaping young minds. Adventure, too, is essential. For four years, I’ve written about Majid on the Silk Road—a boy discovering the civilizations and histories of nations, sharing them with young Arab readers so they know they are not alone in the world. There’s a joy in dialogue with the Other, and pride in seeing that others, like us, have beauty and history, regardless of skin color, nationality, race, or faith.”

Finally, I—Hani Nadeem—who has wandered through the halls of culture for a long, not-always-pleasant journey, must confess: many of those we call “great intellectuals” barely know more than newspaper headlines and never read past a conjunction!

To truly refine our cultural horizon, we must remember that real intellectuals rarely seek glamour or propaganda. They don’t walk toward the spotlight. They are immersed in their papers and their questions. Ashraf Aboul-Yazid is one of them—a true Arab intellectual. We must pay close attention to his work and his creative legacy.