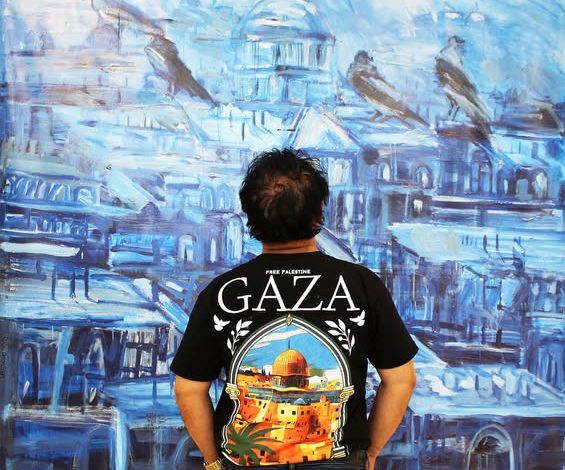

Between his two studios — the first at the Darna Museum on the banks of the Nile in Cairo, and the second in Paris within sight of the Seine — the Egyptian painter and novelist Abdel Razek Okasha created his monumental series The Gaza Epic. Between these two rivers, colors flowed and ideas took flight; the pulse of the brush rose as it struck the palette, so that the world might hear the sound of pain and defiance. Palestine has never been distant from Okasha’s artistic universe; it has always lived in his heart — not only through his past, present, and future paintings, but through his unwavering call for the restoration of rights to their rightful owners and for respect toward the humanity of Palestine’s historic people: the Palestinians.

Among the foundational works of this epic, several paintings accompany the grievous events that the people of Gaza have endured over the past two years — years of annihilation and siege, during which the silence of many was deafening, while the voice of Okasha’s colors rose in protest.

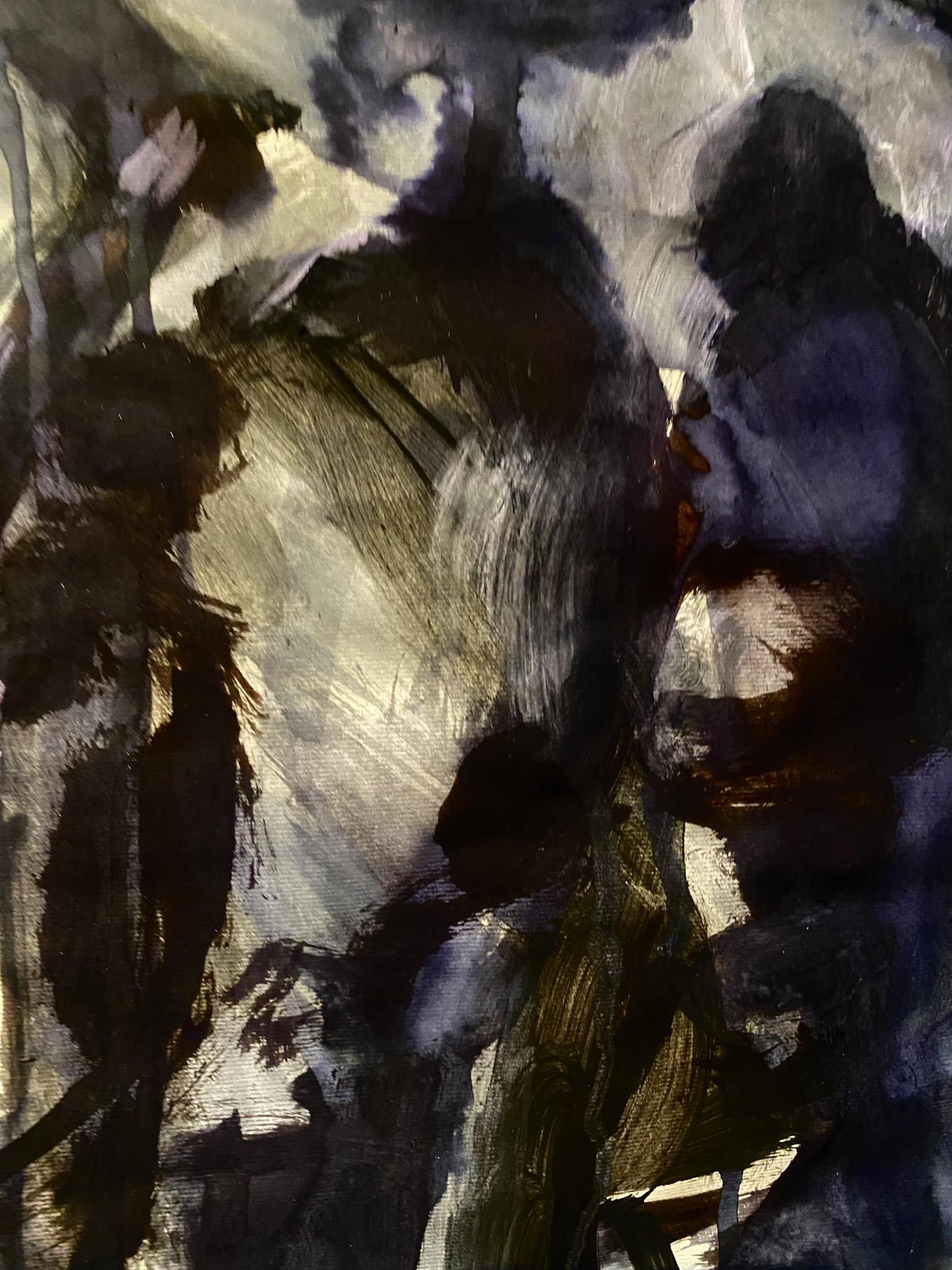

The first painting in The Gaza Epic series is a dense, dramatic moment — both aching and rebellious. The human forms are drawn with broad, dark strokes; their features dissolve into the shadows, like wandering souls amid smoke and dust. The dominant black is not merely a background — it is the protagonist of the scene — opposed by flashes of grey-white light that gleam like a frail hope or the flash of an explosion, uncertain whether it is the dawn of freedom or the fire of ruin.

Compositionally, the artist builds upon a circular, ascending motion: it begins below, where bodies intertwine and shadows coil, then rises upward as if in a collective cry or a prayer ascending through the wreckage. This visual structure endows the painting with an inner rhythm, like a funeral hymn rising through the air of war.

Here, a dual symbolism unfolds — the heavy blackness is not death but martyrdom; the white voids are not light but the memory of those who remain to bear witness. The absence of precise detail liberates the image from individuality, transforming it into an expression of collective agony — Gaza as symbol, not geography. This painting does not merely document a moment of war; it reveals the consciousness of an artist who perceives in tragedy a spiritual and aesthetic energy — one that shapes beauty from devastation and turns the cry into a visual silence that speaks.

The second work, Gaza Burns (oil on canvas, 220 × 200 cm), is an expressionist composition charged with the energy of color and movement, embodying a human and political tragedy that transcends the local to attain a cosmic dimension. Deep crimson, scorched violet, and burnt umber dominate — the hues of fire, blood, and ash — interwoven with flashes of blue and golden yellow, symbols of hope or remnants of life amid ruin. This tension between the heat and coolness of color creates a dramatic pulse akin to the struggle for survival itself.

The lines are fluid and impetuous, surging from above toward the center like rising flames or souls ascending through the blaze. This upward thrust evokes an internal explosion, as if the city — Gaza — has been lifted from the ground, turning into drifting ash and echoes of screams.

At the painting’s heart stands an archway, perhaps the gate of the city or the entrance to a destroyed home, engulfed in fire. Around it, spectral faces and bodies emerge — distorted, interwoven with the texture of the paint in a tragic unity. These faces are not defined, yet they are present: witnesses, praying, or crying out — fragments of humanity suspended in the inferno.

The Final Painting: Al-Ma’madani Hospital

The final painting in this reading of Abdel Razek Okasha’s Gaza works bears the title Al-Ma’madani Hospital. Whether it belongs to the Gaza Burns series or stands as an independent piece, it represents the pinnacle of human expression in the face of one of the most harrowing scenes in modern Palestinian memory — the bombing of a hospital that was meant to be a sanctuary for the wounded, but instead became a wound itself.

The colors in this work — as suggested by its title and the context of Okasha’s artistic journey — oscillate between dark crimson, burnt brown, and opaque gray, invoking fire, ash, and ruin. Yet what arrests the eye are the pale flickers of yellow and white light, glimmering above the debris like the last remnants of lamps — or the lingering souls that refused to leave. Here, color ceases to be a mere visual element and transforms into a narrative language, telling the story through silence.

Shadows, rather than serving as a background as in classical compositions, are part of the event itself. The light does not descend from an external source — it emanates from within the wound, from the heart of the explosion. This inner luminosity lends the painting a metaphysical dimension, as though pain itself has become the origin of light.

The compositional structure revolves around a central axis — perhaps representing the hospital building or its main emergency hall — surrounded by fragments, bodies, and silhouettes caught in a circular motion. This orbiting movement suggests that death is not an ending but a recurrence, a daily cycle. Thus, the painting transcends documentation, rising to the level of tragic symbolism — the eternal return of catastrophe.

In the human imagination, a hospital symbolizes rescue, care, and healing. Yet in this painting, it becomes a site of collective death — the artist’s most searing visual paradox, the collapse of meaning itself. The bombing of the hospital destroys not only walls, but the very idea of humanity.

The Absent-Present Human

In many depictions of catastrophe, the human figure is not explicitly drawn; yet it remains as an imprint — a trace, a shadow lingering on the wall. Okasha conveys the presence of the victims through their absence, giving the scene a doubled emotional force.

The title Al-Ma’madani opens a dual space between the sacred and the human. In Christian tradition, the Baptist is a symbol of purity and water — yet in this painting, water has turned to blood, and the sky to flame. The artist seems to reread the tragedy on a cosmic scale, where even the sacred suffers.

The technique of oil on canvas grants this and its companion works a tactile depth that intensifies emotional resonance. The brushstrokes are fierce, hurried — as if painted by a trembling hand in the instant of shock. The painting does not seek beauty; rather, it exposes its cruelty. It belongs to the post-aesthetic realm, where beauty is born of bareness and truth.

Okasha’s paintings are not only seen — they are heard. One can sense the sirens, the cries, the bodies lifted from beneath the rubble — all embodied through the movement of color and light. This is not merely a painting about a Palestinian tragedy; it is about the collapse of human conscience in the age of the image. The artist does not depict the crime — he sculpts the scream.

Like Picasso’s Guernica, Okasha’s Al-Ma’madani Hospital is not a documentary image but an icon of resistance — a work that writes tragedy in color, not in blood. It is marked by a rare sincerity of emotion and a profound capacity to transform pain into creative energy, compelling the viewer to confront both their humanity and their moral silence.

This is a painting that turns art into testimony — and the brush into a visual conscience that refuses to be still.

Bottom of Form