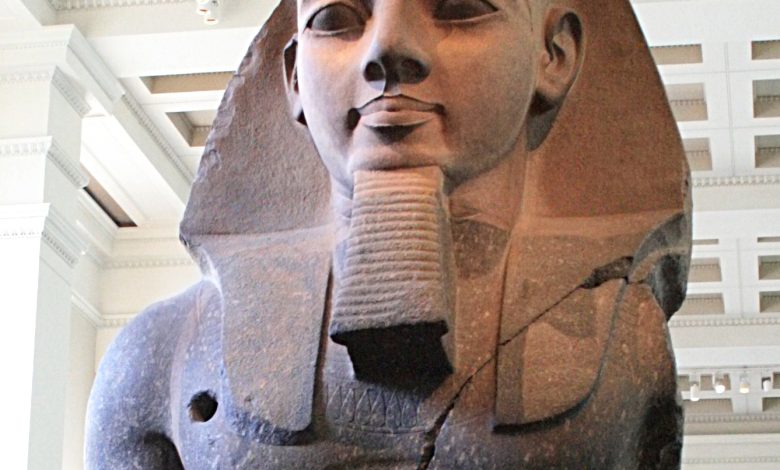

When we speak of Ramesses II, we are not merely referring to a great king, but to a decisive moment in the history of ancient Egypt—a moment when the concept of kingship reached its fullest political, religious, and civilizational expression. Ramesses II was not simply a ruler who sat on the throne for a long time; he was a comprehensive civilizational project who shaped Egypt’s image at home, consolidated its prestige abroad, and left his mark on both stone and memory.

Ramesses II belonged to the Nineteenth Dynasty and ascended the throne at a young age, combining youthful ambition with the wisdom gained through experience. He ruled for nearly sixty-six years, a duration rare in the history of kings, which enabled him to achieve what few others could. This long span of rule was not a historical void, but a period of construction, consolidation, and conscious planning for eternity.

Militarily, Ramesses II is closely associated with the famous Battle of Kadesh against the Hittites, one of the most extensively documented battles of the ancient world, carved on temple walls. Historians may debate its military outcome, but what is certain is that Ramesses emerged victorious politically and ideologically. He presented himself as the heroic king who faced danger alone, protected by the gods, restoring cosmic balance—Ma’at. More importantly, this confrontation concluded with the oldest written peace treaty in history, affirming that Ramesses was not merely a man of war, but a statesman who understood the value of peace and stability.

Militarily, Ramesses II is closely associated with the famous Battle of Kadesh against the Hittites, one of the most extensively documented battles of the ancient world, carved on temple walls. Historians may debate its military outcome, but what is certain is that Ramesses emerged victorious politically and ideologically. He presented himself as the heroic king who faced danger alone, protected by the gods, restoring cosmic balance—Ma’at. More importantly, this confrontation concluded with the oldest written peace treaty in history, affirming that Ramesses was not merely a man of war, but a statesman who understood the value of peace and stability.

On the political level, Ramesses II governed a vast empire with remarkable intelligence, relying on diplomacy alongside military power. He strengthened international relations through dynastic marriages, taking foreign princesses as wives—a move that reflects a deep understanding of ancient international politics, where family ties and bloodlines were integral to systems of rule.

Architecturally, Ramesses II seems present at nearly every major archaeological site in Egypt. The temples of Abu Simbel, the Ramesseum, and his monumental additions to Karnak and Luxor are not merely stone structures, but carved political and religious texts that address both eye and mind. Ramesses understood that architecture is the language of eternity, and that stone is the ideal medium between time and authority.

Religiously, Ramesses presented himself as the son of Ra, chosen by the gods to preserve cosmic order. As he advanced in age, he transformed from a king protected by the gods into a quasi-divine being, venerated during his lifetime and deified after his death. Here we see how Egyptian royal ideology reached its peak during his reign, as the king became identified with the very idea of the cosmos.

The greatness of Ramesses II does not lie solely in the abundance of his monuments or the length of his reign, but in his ability to craft a complete image of the pharaoh: the commander, the priest, the builder, the diplomat, and the symbol. For this reason, his name remained alive through the ages and became the standard by which the greatness of later kings was measured.

In the end, Ramesses II was not merely a page in a history book; he was an entire chapter of Egyptian civilization—a chapter that tells us clearly: here ancient Egypt reached the summit of its glory, and here the king stood face to face with time… and prevailed.