An Anatomy of Deception:

Tyranny and Geopolitical Hypocrisies

in “Western and Oriental Tyrants”

By Bill F. Ndi,

President Pan African Writers Association, (PAWA),

Tuskegee University

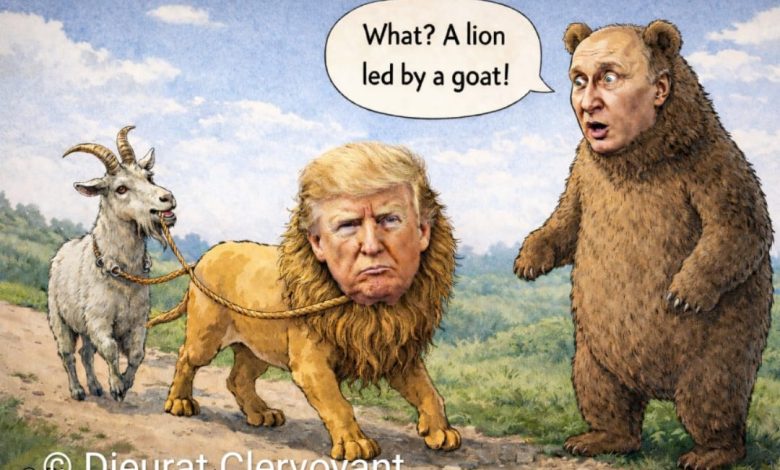

During this age of infobesity, the landscape of contemporary global politics and tyranny rarely announces itself with overt brutality alone. More often, it operates through a sophisticated architecture of deception, wrapping violent intent in the language of national security, salvation, diplomacy, Good, and divine will. Endeavoring to disentangle this rhetoric from reality is one of the most urgent critical tasks of our time given that we are overwhelmed with fake news, alternate fact, virtual reality, and conscious cultivation of ignorance—agnotology—fueled by political rabble-rousing and racially divisive rhetoric. Goaded by this and recent happenings in the world, I felt the need to elucidate these current geopolitical happenings by examining a short 14-line poem, “Western and Oriental Tyrants.” In a strange twist, the US president Donald Trump in an act that wreaks of gross ignorance listed Morocco among countries not very much welcomed to the US. It is worth noting that the very first country to recognize the United States of America as a country was Morocco in December of 1777. Also, could be mentioned recent developments in Venezuela, Greenland, Nigeria, The Cameroons, to name but a few. Against this backdrop, literature, with its capacity for nuance and symbolic depth, must serve as an indispensable tool in this endeavor for Africa, Africans, and Afro descendants to wise up. Literature allows us to see past political performance and into the mechanisms of power and control. The poem here below is a clear example of this assertion and serves as a diagnostic tool for dissecting deception and hypocrisy of the geopolitical landscape as we know it.

Western and Oriental Tyrants

One can’t help his people, yet pledges help

While killing his own and encouraging

Resistance to the Oriental killing

Every dream and promise heaven would help

Them fight the bully who claims to always

Want to negotiate a deal till it fades

Into that which he means, he would use blades

To cut through any cord causing delays

To the maturation of his malice

And snare laid to entrap the innocent

Who believes his promise to be God-sent

Except he drinks from this word filled chalice

Flagging the mines for none to be a prey

And victim of a tyrant who can’t pray.

“Western and Oriental Tyrants,” is a concise yet devastatingly powerful and unflinching examination of this modern political condition with breadth taking and sweeping scope of an epic like the Epic of Gilgamesh. In just fourteen lines, the poem constructs a forensic analysis not of two equal evils, but of a global political narrative that uses one to legitimize the other. Through a deliberately imbalanced poetic structure, paradoxical imagery, and potent metaphors, this poem dissects the intricate hypocrisy of the Western-coded power player, exposing how the language of liberation is often a “snare” meticulously laid for the innocent. Therefore, this op-ed focuses its critique almost exclusively on the Western figure. The poem functions as a crucial political warning against interventionist logic itself. By analyzing the poem’s subversion of its own comparative title, its exploration of deceptive language, and its subversive use of poetic form, we can understand the poem’s ultimate purpose. The poem aims to equip the reader with the critical awareness needed to dismantle the rhetorical traps of the modern tyrant who is bent on marginalizing knowledge production and disciplines that encourage any form of critical thinking.

The Paradox of the Twin Tyrants

The Paradox of the Twin Tyrants

The poem’s title establishes a comparative framework, inviting a parallel analysis of “Western and Oriental Tyrants.” However strategic this juxtaposition is, it is a masterful railroading. It is not a presentation of a symmetrical study of two equivalent figures. The poem’s body focuses its forensic lens almost exclusively on the Western-coded tyrant’s intricate pathology: a skin thinness. Narcissism. And the Alpha male syndrome coupled with ignorance and its cultivation. By subverting the expectation of equivalence, the poet dismantles the geopolitical narrative that casts these “Western and Oriental Tyrants” as simple ideological opposites. The poem pits the “Oriental” tyrant primarily as a rhetorical tool—a distant, abstract evil used to launder the more immediate and concrete violence of his Western counterpart.

The Self-Devouring Savior

The poem opens with a harsh and damning paradox that defines the Western tyrant’s core nature: “One can’t help his people, yet pledges help/While killing his own…” This characterization is crucial. It defines tyranny not as external aggression but as a profound and hypocritical betrayal of one’s own populace, subjects, citizens, etc. The tyrant’s power is built on a foundation of internal violence, a self-devouring impulse where the promise of aid is directly contradicted by the act of murder and violence meted upon his own. This exposes the political performance of salvation as a hollow sham for domestic oppression, establishing from the outset the specific brand of hypocrisy that will end up as the poem’s central subject.

The Geopolitical Foil

This internal hypocrisy is immediately projected onto the global stage through cynical mechanics of interventionist foreign policy. The tyrant is depicted as simultaneously “killing his own” and: …encouraging/Resistance to the Oriental killing/Dreams… The “Oriental” tyrant’s violence—the abstract and metaphorical act of “killing dreams and promises”—is differentiated from the Western tyrant’s literal act of “killing his own.” This distinction underscores the latter’s hypocrisy. The Western tyrant condemns a less concrete crime abroad while manufacturing moral outrage to legitimize his own power, distract from his own tangible atrocities, and posture as a global arbiter of justice. We need not look hard to find this parallel in 2026. Thus, this “encouraging / Resistance” is not a genuine commitment to freedom but a strategic move on a geopolitical chessboard, where the abstract suffering of a distant population is exploited to sanctify a self-serving agenda of an ego maniac. This symbiotic violence is sustained not by force alone, but by a carefully constructed rhetorical edifice, which the poem, “Western and Oriental Tyrants” proceeds to dismantle through careful and painstaking engineering and reverse engineering of the language of deception.

The Language of Deception

The foregoing analysis has established the tyrant’s hypocritical actions and now, focus should be turned to the tyrants’ primary weapon, viz. language. The poem’s central argument hinges on the idea that political violence is preceded and enabled by rhetorical deception. A close look at the key metaphors the poem uses will reveal how public discourse is weaponized to “entrap the innocent,” transforming words of hope and negotiation into instruments of malice. This explains how the poem navigates from Diplomacy to “Blades.” The poet captures the tyrant’s duplicity in his approach to negotiation. He “claims to always / Want to negotiate deals,” a public performance of reason and diplomacy. However, this facade is short-lived and designed to last only “until it fades / Into that which he means.” The poem exposes the tyrant’s true intent with a single, brutal image: “he would use blades.” This metaphor brings to the fore the rift between political pronouncements and violent reality. Diplomacy is not a genuine process for the tyrant, but a strategic delay, a rhetorical smokescreen deployed to muddy the waters before inevitably resorting to force. The “blades” represent the raw, unmasked violence that underpins the tyrant’s rule, a truth that lies waiting just beneath the shiny surface of political speech disguised in morality and divinity.

The “God-Sent” Snare and the Poisoned “Chalice”

The poem reveals tyrants at work co-opting the language of morality and divinity. The tyrant’s promise is presented as “God-sent,” a manipulation designed to disarm skepticism and command absolute belief. This appropriation of divine authority becomes the ultimate rhetorical snare, as it frames obedience as a moral duty and dissent as a form of sacrilege. This deception is crystallized in the complex metaphor of the “word filled chalice.” A chalice, a sacred vessel, often associated with communion and life, in the tyrant’s hands, is filled with poisonous words of propaganda. The poem presents a deeply ambiguous condition for survival: the innocent is trapped “Except he drinks from this word filled chalice.” This conditional logic suggests two profound interpretations. First, that one must critically “ingest” the poison—analyze the tyrant’s rhetoric—to become inoculated against it. A second, more dreadful reading suggests that only the person who has already drunk from the chalice, who has been victimized and understands the working of its poison firsthand, can truly recognize the danger and effectively begin “Flagging the mines.” The poem thus becomes a warning born from bitter firsthand experience, a testament to the idea that true critical awareness is forged in the crucible of survived deception and calls for subversion in its highest form.

In poetry, form is never merely a container; it is an active participant in the creation of meaning. The choice of Sonnet form here is Subversive. The 14-line structure, reminiscent of a sonnet, is a deliberate and powerful artistic decision that mirrors the poem’s central theme. The poet creates a philosophical tension that amplifies its message and grim political commentary; this form traditionally associated with love and beauty. The poem’s somber, cautionary tone further reinforces its function as a sharp political statement.

The sonnet has historically been the chosen form for meditations on love, beauty, and intimate feeling. Ndi disrupts this tradition entirely by using it to meditate on political ill-will, malice, hypocrisy, political violence, and geopolitical gangsterism. His decision to anatomize “malice,” hypocrisy, and political violence within this elegant container is a powerful act of formal critique. The poem’s form mimics the tyrant’s method; just as the tyrant uses the beautiful language of diplomacy and “God-sent” promises to mask his “blades,” the poem uses the beautiful structure of the sonnet to contain the brutality and harshness of the subject. The rigidly ordered aesthetic of the 14-line form is a direct structural metaphor for the polished facade of the tyrant’s rhetoric. This tension does not merely contrast beauty and ugliness; it reveals how the former is often deployed to conceal the latter. Such is done with both mood and tone that spell the tyrant’s moral emptiness.

Mood, Tone, and Moral Emptiness

The moral emptiness of the tyrant in this poem creates an overall mood of grim caution. Its tone is declarative and unflinching, presenting its analysis as a certainty, not as a possibility. This uncanny sense of foreboding culminates in the final, devastating line, which offers the ultimate definition of the tyrant’s character: “… a tyrant who can’t pray.” This concluding image is not about religious observance but about moral and spiritual ineptitude. To be unable to pray is to be cut off from humility, introspection, and any sense of a higher moral authority. The tyrant is defined by a profound void—an emptiness where empathy, grace, and redemption might otherwise reside. This final portrait renders the tyrant utterly irredeemable and reinforces the poem’s clear warning. With such a figure, there can be no negotiation, only recognition and vigilance.

Conclusion: “Flagging the Mines” for the Modern Age

Bill F. Ndi’s “Western and Oriental Tyrants” is a masterful poetic work of political art that dissects the anatomy of modern hypocrisy with surgical precision. In all, he subverts the expectation of a balanced comparison making the poem to direct its critical fire at the Western-coded power that uses the specter of a distant “Oriental” evil to mask a core of violent and voracious self-interest. Through its potent metaphors of blades, snares, and a poisoned chalice, it illuminates how benevolent rhetoric is weaponized to control and consume the innocent, while its very form—a sonnet for a tyrant—enacts this deception structurally. The poem’s ultimate purpose, its most profound political act, is articulated in its penultimate line: “Flagging the mines for none to be a prey.” This is the work of the poet as truth-teller and cartographer of a treacherously mined political landscape. The poem itself is a warning sign, a flag planted to mark the hidden dangers that lie beneath the surface of official narratives. It is an act of solidarity with the potential “prey,” designed to equip the reader with the critical awareness needed to see past the performance of power and recognize the trap before it springs. In a world where political narratives are constantly contested and manipulated, “Western and Oriental Tyrants” serves as a timeless and essential reminder of the need for unceasing vigilance against the snares of power, wherever they may be laid. When next you hear a western politician spewing out promises of benevolences, remember “Western and Oriental Tyrants.”

Bill F. Ndi’s “Western and Oriental Tyrants” is a masterful poetic work of political art that dissects the anatomy of modern hypocrisy with surgical precision. In all, he subverts the expectation of a balanced comparison making the poem to direct its critical fire at the Western-coded power that uses the specter of a distant “Oriental” evil to mask a core of violent and voracious self-interest. Through its potent metaphors of blades, snares, and a poisoned chalice, it illuminates how benevolent rhetoric is weaponized to control and consume the innocent, while its very form—a sonnet for a tyrant—enacts this deception structurally. The poem’s ultimate purpose, its most profound political act, is articulated in its penultimate line: “Flagging the mines for none to be a prey.” This is the work of the poet as truth-teller and cartographer of a treacherously mined political landscape. The poem itself is a warning sign, a flag planted to mark the hidden dangers that lie beneath the surface of official narratives. It is an act of solidarity with the potential “prey,” designed to equip the reader with the critical awareness needed to see past the performance of power and recognize the trap before it springs. In a world where political narratives are constantly contested and manipulated, “Western and Oriental Tyrants” serves as a timeless and essential reminder of the need for unceasing vigilance against the snares of power, wherever they may be laid. When next you hear a western politician spewing out promises of benevolences, remember “Western and Oriental Tyrants.”

Bill F. Ndi’s “Western and Oriental Tyrants” is a masterful poetic work of political art that dissects the anatomy of modern hypocrisy with surgical precision. In all, he subverts the expectation of a balanced comparison making the poem to direct its critical fire at the Western-coded power that uses the specter of a distant “Oriental” evil to mask a core of violent and voracious self-interest. Through its potent metaphors of blades, snares, and a poisoned chalice, it illuminates how benevolent rhetoric is weaponized to control and consume the innocent, while its very form—a sonnet for a tyrant—enacts this deception structurally. The poem’s ultimate purpose, its most profound political act, is articulated in its penultimate line: “Flagging the mines for none to be a prey.” This is the work of the poet as truth-teller and cartographer of a treacherously mined political landscape. The poem itself is a warning sign, a flag planted to mark the hidden dangers that lie beneath the surface of official narratives. It is an act of solidarity with the potential “prey,” designed to equip the reader with the critical awareness needed to see past the performance of power and recognize the trap before it springs. In a world where political narratives are constantly contested and manipulated, “Western and Oriental Tyrants” serves as a timeless and essential reminder of the need for unceasing vigilance against the snares of power, wherever they may be laid. When next you hear a western politician spewing out promises of benevolences, remember “Western and Oriental Tyrants.”