The author : Adel Drgham

Adel Drgham (1968) is an Egyptian critic and university professor who has authored numerous works, including In Narrative Fiction, Cognitive Awareness and the Evolution of Poetics, The Historical Novel: From History to Identity, and The Novel and Knowledge. In the field of translation, he has published Classical and Postclassical Narratology by David Herman and Gerald Prince.

Translated by Dr.Salwa Gouda

Dr Salwa Gouda is an accomplished Egyptian literary translator, critic, and academic affiliated with the English Language and Literature Department at Ain Shams University. Holding a PhD in English literature and criticism, Dr. Gouda pursued her education at both Ain Shams University and California State University, San Bernardino. She has authored several academic works, including Lectures in English Poetry and Introduction to Modern Literary Criticism, among others. Dr. Gouda also played a significant role in translating The Arab Encyclopedia for Pioneers, a comprehensive project featuring poets, philosophers, historians, and literary figures, conducted under the auspices of UNESCO. Recently, her poetry translations have been featured in a poetry anthology published by Alien Buddha Press in Arizona, USA. Her work has also appeared in numerous international literary magazines, further solidifying her contributions to the field of literary translation and criticism.

Simulating Reality or Discourse:

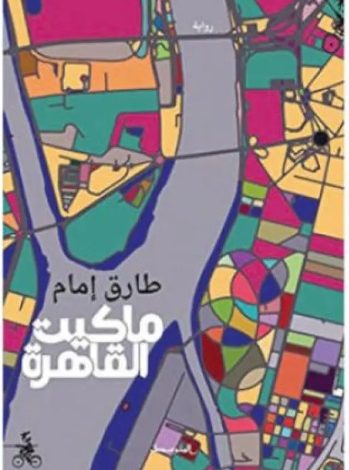

The Fantasy Interpretation of the City in Tariq Imam’s The Maquette of Cairo

Adel Drgham

Tariq Imam’s novel The Maquette of Cairo does not present a conventional narrative structure with a clear plot confined to a specific timeframe. Instead, the story is fragmented, its edges blurred, more erased than revealed, lacking a definitive beginning or end. It offers a longitudinal cross-section of the city at particular moments in time, yet this cross-section is bound to a circular structure marked by repetition and resemblance. Time in the novel merges the immediate, the past, and the present, suggesting the possibility of embodying these temporal dimensions simultaneously. Characters from each era possess the ability to observe a preceding phase, a moment in formation, or a future yet to unfold.

Tariq Imam’s novel The Maquette of Cairo does not present a conventional narrative structure with a clear plot confined to a specific timeframe. Instead, the story is fragmented, its edges blurred, more erased than revealed, lacking a definitive beginning or end. It offers a longitudinal cross-section of the city at particular moments in time, yet this cross-section is bound to a circular structure marked by repetition and resemblance. Time in the novel merges the immediate, the past, and the present, suggesting the possibility of embodying these temporal dimensions simultaneously. Characters from each era possess the ability to observe a preceding phase, a moment in formation, or a future yet to unfold.

The novel extends attempts to answer existential questions that resurface periodically, particularly after events that shatter logic, impose alternative realities, and open possibilities for change—where the fantastical and the imaginary emerge as legitimate interpretations. The reader cannot help but associate the character of Mrs., with her uncanny dominance and ability to read thoughts during conversations, with figures from Naguib Mahfouz’s The Harafish and Children of the Gabalawi. This connection underscores how knowledge—or the very image of knowledge—shifts across time. Mrs. is deeply tied to Imam’s temporal framework, spanning the Egyptian revolution of 2011, the recent past of 2020, and the future of 2045. In a novel where plot is minimized, the reader encounters an epistemological structure preoccupied with dismantling the walls between binaries: reality and fantasy, truth and falsehood, form and content, past and present.

The novel presents a vision steeped in fragmentation and uncertainty, mirroring the collective disillusionment following major upheavals. This is akin to Origa’s finger—metaphorically killing his father yet remaining stunted, dwarfed—much like his work with miniatures and scaled-down models. The novel, from an oblique angle, grapples with the fate of revolution, observing it through an artistic lens. Revolution, in its ideal form, is tethered to exemplarity, but the shattering of this ideal—or the loss of its foundational premises through intense conflict—reawakens questions of existence, identity, and the forces that shape individual destinies. Unlike Mahfouz’s novels, where metaphysical faith offers solace, here characters are left adrift, retreating to the margins, constructing private fantasies that, at first glance, defy logic but upon closer inspection reveal mechanisms of survival and resilience.

It is impossible to read the novel without linking it to Egypt’s revolution and its aftermath, which profoundly influence its interrogations—not just of politics but of existence itself. This fantastical world does not stray far from Egypt’s sociopolitical reality, and the reader is inevitably drawn into this connection, especially given explicit temporal markers and subtle cues like “the honorable citizens” or the character Billiardo, who loses an eye because he dared—just once—to truly see, know, and understand. The novel states: “For the first time, Billiardo thought that this missing eye was what had once confirmed his existence. Losing it meant losing his identity in the state’s records. In a sense, he was now barred from traveling abroad, from obtaining an ID—as if he were a criminal when he was, in fact, a victim.”

Writing: Simulating Reality or Discourse?

In many of Tariq Imam’s novels, storytelling is not the sole focus, his writing weaves together narrative and theoretical knowledge. While theoretical frameworks heavily influence critical theory, their presence in creative writing is subtler, often masked by craft. In The Maquette of Cairo, postmodern theories are most prominent, especially in deconstructing binaries like real/fake, original/imitation, reality/fantasy, and past/present, while nodding to earlier theories that rigidly demarcated these divides.

The reader confronts this overwhelming theoretical presence in the narrative’s structure. Passages revisit the idea of binaries, such as Mrs. statement to the recipients of the Cairo Work Gallery grant, which blurs the lines between “real” and “fake,” creating ambiguity and overlap. This interrogation of binaries is central to the novel, particularly in its exploration of art and reality: Does art simulate reality, or does it simulate a discourse, a text, or an awareness of reality? And what defines this reality? Here, reality is ambiguous—closer to events, while discourse or text reflects individual agency and production. Imam extends this idea from art to cities: the identity of any city, as per the fantastical book Mansi Agram, is inseparable from its inhabitants’ contributions—the identity of individuals.

Theoretically, reality cannot be grasped directly, as we do not experience it as raw events but through representations—discourses or texts, as postmodern theorists argue. Thus, mimesis is not tied to reality but to texts, opening the door for subjectivity and ideology in every discourse. This justifies the emphasis on individual agency among the grant applicants, particularly in the dialogues of Billiardo and Nude.

This understanding aligns with the novel’s recurring emphasis on language’s power—not to convey reality but to create it. There is no single, stable reality; multiple worlds emerge depending on perspective and creative texts. This explains the repetition of events through different characters’ viewpoints. The “reality” here (if such a thing exists) is fixed, but the narratives presenting it—through Billiardo, Origa, and Nude—are multiple. The maquettes, graffiti, and documentary films attain existential legitimacy as representations of “real” Cairo.

The novel’s preoccupation with this theoretical idea manifests in dismantling the walls between art and reality and between oppressive binaries that still shape our approach to life. Close examination reveals the validity of this direction: Billiardo’s real eye, which he pastes onto his graffiti; the miniatures Mrs. retrieves from her cabinet (airplanes, cars) that move and fly realistically; Nude’s “Mirror Man,” who only appears in reflections and can metaphorically impregnate her—all these elements blur the line between real and unreal, shifting mimesis from reality to texts, from a fixed world to the worlds we continually create.

The destabilization of the rigid boundary between reality and textual/imaginary discourse appears in many details, such as the parallel between life and theater. In the novel’s second part, the narrative creates the illusion of entering a play where each character performs a role. Theater and life mirror each other: actors, prompter, director, and a structured system versus people moving through spontaneous, improvised daily existence. When the prompter vanishes, characters act freely, and the wall between life and theater dissolves. In that moment, equality emerges, and the real/fake, reality/fantasy binaries collapse.

The reader is inevitably struck by Mrs.’ peculiar abilities, which might seem supernatural. Yet, within the life-theater analogy, her power is not divine but mediatory. Her dialogue reveals an uncanny awareness of characters’ thoughts, and her marginalia in Mansi Agram suggests a sacred role—not as creator but as interpreter of existence. This illusion of reality-theater interplay creates ambiguity, merging real and performative identities and erasing hierarchies between truth and illusion.

Clues to this dissolution of boundaries abound, such as Mrs.’ remark about miniatures: “The small will become large,” or her comment to a character: “He couldn’t distinguish between a real building and a fake one—both had abandoned their essence to coexist in his imagination.”

The distribution of characters between worlds mirrors human division in life. Both worlds hold legitimacy: the real is lived, the imaginary is conceived and projected. The novel states: “Between the two cities, Origa lived suspended, like his stance on the scaffold—unable to look at the sun or the ground, for in either case, the result was a fall.”

This dilemma—whether mimesis is tied to reality or textual discourse—pervades the novel, especially in the role of Mansi Agram. The book seems to govern the fictional world and its characters, but if applied to reality, does it remain intact, or does it cede authority to Mrs.’ marginal notes—mere interpretations? This interpretive cycle opens the door to simulating the subjective, personal, and discursive, detached from a collectively perceived reality that no one has fully captured.

This is evident in the contrast between “real” Cairo and its maquette counterpart. Despite formal similarities, the comparison breeds doubt, raising questions about authenticity—between houses, streets, people, and the miniature replicas inside the maquette. The novel describes Origa: “As he tore up the fragile certificates he had no wall to display, Origa realized his only stage was the city—not to adorn it, not to add layers to its masked face, but to strip that mask away.”

The arts of modeling and comics, embodied by Manga (who possesses two memories: one of fantasy, one of reality), serve as tools of exposure, distorting and diminishing reality. They undermine its dominance, asserting individual agency and becoming instruments of unveiling, revealing the flaws beneath apparent perfection.

Yet these miniatures and models are not immune to imperfection. The text hints that the fantastical—rooted in linguistic ambiguity—can yield outcomes as destructive as reality’s pressures. The embodiment of fantasy into reality leads to ruin, akin to the tragic fates in Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum, where characters are destroyed by false interpretations. The Maquette of Cairo similarly concludes: “ Mrs.’ man materialized, while Nude still awaited the incarnation of hers (the Mirror Man), unsure what would follow—though she trusted the free certainty of a fortune-teller that in that deferred moment lay her destruction.”

Circular Time: The Fantastic Interpretation

A key feature of The Maquette of Cairo is its engagement with change across time, tracking transformations in people and urban spaces. The novel observes place and humanity at intervals, collapsing past and future into the present through art’s power to shape identity—one rooted in history yet capable of distorting or undermining reality’s rigid frameworks.

The novel’s core characters are Origa (the son), Nude (the mother), and Billiardo (the symbolic father), with Manga appearing in the fourth and final chapter (added after “The End” of Part Three to clarify ambiguities). This triad anchors the narrative, each tied to distinct temporal moments. Time is destabilized through fantasy: the novel begins in 2045 with an announcement about a grant to model Cairo as it was 25 or 20 years prior, then shifts to Nude’s 2020 documentary, before revealing Billiardo’s 2011 injury. These temporal markers offer a lens for reading the work.

What’s innovative is how these characters’ worlds unfold in parallel despite chronological gaps, as if the author—drawing on string theory and circular time—can move backward and forward instantaneously, redefining time as without beginning or end. Death is not an end but a resurrection, linking back to prior existence. Characters become patterns, shedding old forms for new ones.

Mansi Agram epitomizes this circular time, fragmenting the idea of beginnings or endings. The book exists in a perpetual present, sometimes as fate, other times as an active force. Its portrayal carries a sacred aura—through multiple copies, cryptic marginalia, or the guilt of placing anything above it. All protagonists are bound to it across generations, their connection unidirectional.

Yet certain traits strip the book of sanctity, grounding it in the ephemeral. The name Mansi (“Forgotten”) evokes the past, and each character’s reading starts where their last ended. The book is not collective but personal, rewritten by each individual through choices and actions. It mirrors life’s continuity: “Like Mansi Agram’s book—its pages unnumbered, impossible to revisit—we have no refuge but memory.”

Recurring motifs include improvisation in art and life, and the long paper scraps near the book, hinting at inescapable fate and existential fragility. The fantastic emerges as a defiance of limits imposed by linear time, shattered here into parallel strings that let characters witness their past, engage in the present, and glimpse futures.

Applied to Mrs., circular time reveals her stitching across eras: multiple versions of her exist, from the childhood portrait on the wall to her present incarnation, all endowed with strange powers. She is “the woman who seems from another reality, where faces change literally, not metaphorically—a parallel world,” or, as the novel states, “ Mrs like the city, is everyone and no one.”

Her dominance derives not from knowledge but from being pre-established, immutable—like Origa’s stunted finger, symbolizing an unfinished revolution. Mrs. is Cairo’s foundational face, resisting renewal. Origa remarks: “Who are these people Mrs. speaks for? I’ve only met her here—unless she is everyone, as her face is all faces.” This is confirmed when Nude sees past female rulers’ faces superimposed on Mrs. body in yellowed newspaper clippings—triumphs of permanence.

Interpreting Mrs. as a force that voids the new to sustain old systems aligns with the marginalized protagonists who, through fantasy, attempt to forge alternatives. Graffiti, maquettes, and comics strip dominant narratives of their authority, exposing their fragility.

The characters’ pseudonyms (Origa, Nude, Billiardo, Manga)—distinct from Egyptian naming conventions—reflect their outsider status, rejecting heroism in favor of singularity. Their signatures throughout the novel underscore this individuality.

These protagonists are all marginal rebels, defying hegemony and stability, paying a price for their dissent. Their struggles are framed by fantastical models (Hilary Khamis, Jorge Khalid, Kolehmainen Medhat), whose Egyptian origins suggest a localized imaginary. Their influence is less about imitation than about crafting a vision open to the other, perpetually self-revising, monitoring loss and in addition to the city’s ever-shifting identity.

Adel Drgham (1968) is an Egyptian critic and university professor who has authored numerous works, including In Narrative Fiction, Cognitive Awareness and the Evolution of Poetics, The Historical Novel: From History to Identity, and The Novel and Knowledge. In the field of translation, he has published Classical and Postclassical Narratology by David Herman and Gerald Prince.

Adel Drgham (1968) is an Egyptian critic and university professor who has authored numerous works, including In Narrative Fiction, Cognitive Awareness and the Evolution of Poetics, The Historical Novel: From History to Identity, and The Novel and Knowledge. In the field of translation, he has published Classical and Postclassical Narratology by David Herman and Gerald Prince. Dr Salwa Gouda is an accomplished Egyptian literary translator, critic, and academic affiliated with the English Language and Literature Department at Ain Shams University. Holding a PhD in English literature and criticism, Dr. Gouda pursued her education at both Ain Shams University and California State University, San Bernardino. She has authored several academic works, including Lectures in English Poetry and Introduction to Modern Literary Criticism, among others. Dr. Gouda also played a significant role in translating The Arab Encyclopedia for Pioneers, a comprehensive project featuring poets, philosophers, historians, and literary figures, conducted under the auspices of UNESCO. Recently, her poetry translations have been featured in a poetry anthology published by Alien Buddha Press in Arizona, USA. Her work has also appeared in numerous international literary magazines, further solidifying her contributions to the field of literary translation and criticism.

Dr Salwa Gouda is an accomplished Egyptian literary translator, critic, and academic affiliated with the English Language and Literature Department at Ain Shams University. Holding a PhD in English literature and criticism, Dr. Gouda pursued her education at both Ain Shams University and California State University, San Bernardino. She has authored several academic works, including Lectures in English Poetry and Introduction to Modern Literary Criticism, among others. Dr. Gouda also played a significant role in translating The Arab Encyclopedia for Pioneers, a comprehensive project featuring poets, philosophers, historians, and literary figures, conducted under the auspices of UNESCO. Recently, her poetry translations have been featured in a poetry anthology published by Alien Buddha Press in Arizona, USA. Her work has also appeared in numerous international literary magazines, further solidifying her contributions to the field of literary translation and criticism.