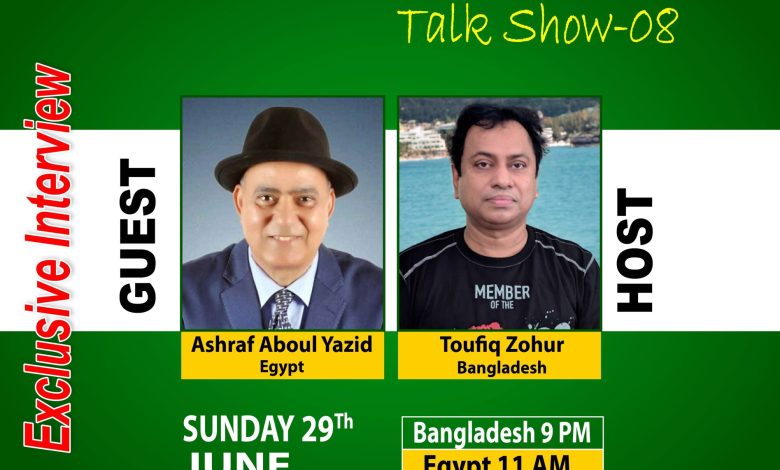

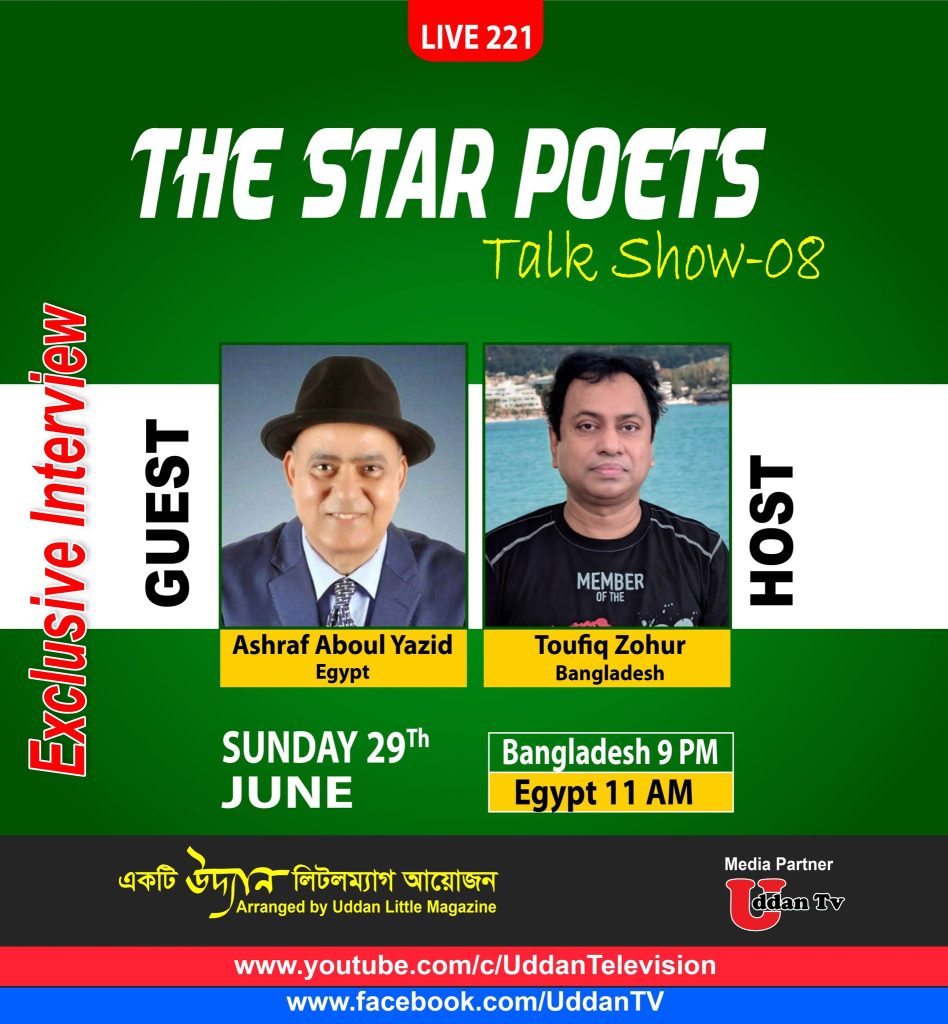

Welcome everyone to the 221th episode of Uddan Little Magazine’s live show We are working in different branches of literature. We want to build a sky of Literature. We are taking interview for the next generation from famous poets Who are Living across the World . Which is being shown on our YouTube channel. On Sunday, June 29 at 9 pm evening Bangladesh time, 6 pm Egyptian time, an interview with international , the Egyptian Editor, poet, novelist, and journalist Ashraf Aboul-Yazid (Ashraf-Dali)

“Note: These are some excerpts of the full interview”

When did you first start to write?

I began writing seriously in my early teenage years, driven by a deep connection to the Arabic language and a desire to give voice to the silent stories of my surroundings. My first published work appeared when I was just a school student.

I remember that I used to draw the pages and leave blank spaces in the papers, then go to a typing office to have those spaces filled with the stories I wrote. It was a colorful book with only one copy, but my friends would take turns borrowing and reading it.

While my peers were playing football, I seized every opportunity to go to the school library and read its books, whether they were stories for young readers or for adults.

I was also an avid letter writer, sending letters to friends—both in Egypt and around the world—in the form of handmade magazines, adorned with poetry, stories, and drawings.

Who is the most influential person in your life as far as writing?

My father had a subtle yet powerful influence. He forbade us from playing in the street, but instead, he allowed me to make an arrangement with the newspaper vendor to borrow any book or magazine I liked. I especially loved the Tintin comic series, as well as literary magazines.

I’ve been influenced by many literary icons, in prose I could bring the names of Yehya Haqqi, Taha Hussain, Al Aqqad and Naguib Mahfouz. In poetry I preferred the voices of Salah Abdel Sabour, Amal Donqul and Mohammed Afifi Matar. But perhaps the spirit of al-Mutanabbi echoes most in my work — for his wisdom, depth, and poetic challenge. In real life, the encouragement of family and the mentorship of literary elders in my hometown Benha shaped my early journey.

What is the definition of poetry in your thought?

Only human beings can create poems, and this could make the difference between them and everything around.

Poetry is a soul’s testimony. It is the unseen melody of pain and hope, where language becomes an instrument of truth, resistance, and dreams.

I am indebted to poetry, for it taught me empathy, led me to seek beauty, and inspired me to respect others.

What power is there within the poet’s pen?

The pen is both a sword and a candle. It resists darkness and fights injustice — not with bloodshed, but with illumination.

Let me give you an example: yesterday and today, poets from 110 countries are gathering in a video broadcast, responding to the call of the World Poetry Movement to read love poems for Gaza. The poems could not stop the war of extermination, but they proclaim our shared humanity in the face of this brutal aggression against a people defending their homeland and dreaming of living safely on their own land.

The Movement hopes that this global poetic initiative will serve as a cry of conscience and a stand for dignity, expressing—through words and creativity—human solidarity with Gaza, and stirring collective awareness toward ending the occupation and rejecting genocide.

Is there something regarding writing that you would like to achieve that you have not yet achieved?

I’ve written and been translated in many languages, but I still dream of a Global House of Pens, a space where writers and poets from every culture can create, translate, and transform the world together.

I call on civil society institutions to establish residency projects for creatives, where local authors can live and work alongside visiting writers from around the world. These projects should form a simple, evolving network of guests and sponsors—one that builds lasting roots between dialoguing cultures. A similar initiative was launched by the Nigerian writer and doctor Wale Okediran, and another exists in Uzbekistan under the patronage of the poet Azam. I hope that the poet and artist Margarita Al will include such a project on the list of future initiatives for the World Organization of Writers (WOW), which she leads.

Do you write anything besides poetry?

Yes, I am also a novelist, journalist, travel writer, and translator. Literature must cross forms to fully serve truth.

I have published four novels, four travel literature books, and around ten books for children and young adults.

In addition, I have authored works of autobiography, art criticism, and translations. I am particularly interested in bringing distinctive poetic and narrative literatures into the Arabic language.

Poetry has no boundaries – do you believe poetry can change the world by its own dream way?

Yes, I do believe that poetry can change the world—not in the conventional way of political decrees or economic systems, but in its own dreamlike, resonant, and enduring way. Poetry has no boundaries because it speaks directly to the soul, uniting us through the shared language of emotion, imagination, and truth. In a world increasingly shaped by noise, distraction, and division, poetry offers a quiet revolution—one that invites us to pause, to feel, and to see differently.

Poetry does more than describe the world; it creates worlds. Each poem is a small act of world-building, a speculative journey into alternative futures, where values like justice, beauty, empathy, and peace are not only possible but deeply felt. In this way, poetry becomes a form of resistance and imagination. It dares to dream of what is not yet visible. It sketches the architecture of hope and maps territories of the soul that politics and technology often overlook.

Furthermore, poetry is a form of inner and outer travel. Through the lyric voice, the poet embarks on a journey into the self—exploring memory, trauma, longing, and love—while simultaneously reaching out to the other, the stranger, the distant heart. In this dual voyage, poetry becomes a bridge, connecting isolated islands of human experience and forging empathy across languages, cultures, and histories.

Poetry can transform individual consciousness, and through that, it sows the seeds of collective awakening. A single verse may not end a war or dismantle an empire, but it can change the heart of someone who will. It can reframe the narrative, shift the lens, and remind us of our shared humanity. In the face of injustice, poetry becomes witness; in moments of despair, it becomes song; and in the silence between people, it becomes dialogue.

So yes, I believe poetry can change the world—not through domination, but through resonance; not through force, but through vision. Its power lies in the dream it keeps alive: that another world is possible, and that the journey toward it begins with a word.

Few numbers of readers all over the world are reading modern poetry. One day there will be no readers. What do you think?

Poetry has never depended on crowds. Even if only one heart listens, that is enough to start a revolution. Poetry is the language of the timeless few.

To begin with, I write the poem for myself. But once it is heard or reaches someone who receives it, it becomes for the other. The idea is that the avenues of readership have branched out; seminars, newspapers, and books are no longer the only platforms for publication. There are millions of pages on social media filled with poetry—much of it worthy of being celebrated as true poetry. The reader still exists, but through a different medium. And the poet must be ready to be present through various platforms and technologies.

How many poetry books have you published? Besides poetry writing do you write anything?

There is a diverse body of work spans novels, poetry, travel literature, children’s literature, critical studies, and translations. My literary journey reflects a deep engagement with cultural dialogue, artistic expression, and storytelling across genres and generations.

My fiction includes four novels—Shamawes (2008), Backyard Garden (2011), 31 (2011), and The Interpreter (2017)—each exploring different facets of identity, memory, and human experience.

As a poet, I have published six collections, starting with Whispers of the Sea (1989) and culminating in Poems (2024), showcasing my lyrical voice and philosophical depth.

A seasoned traveler, I have enriched Arabic travel literature with titles such as A Traveler’s Memoir (2008), A River on Travel (2015), Moroccan Caravan Tales and Damascene Days (2021), blending observation with cultural reflection.

My contributions to children’s literature, exceeding ten books, include the award-winning My Cat Writes a Book (2020), and My Father the Cartographer (2025), offering imaginative stories and educational narratives to younger readers.

As a translator, I have introduced Arabic readers to significant works from Korean, Indian, Tatar, Azerbaijani, and other literatures. My translations include I am Surrealism by Salvador Dalí and Ten Thousand Lives by Ko Un, among others, reflecting my commitment to literary bridges.

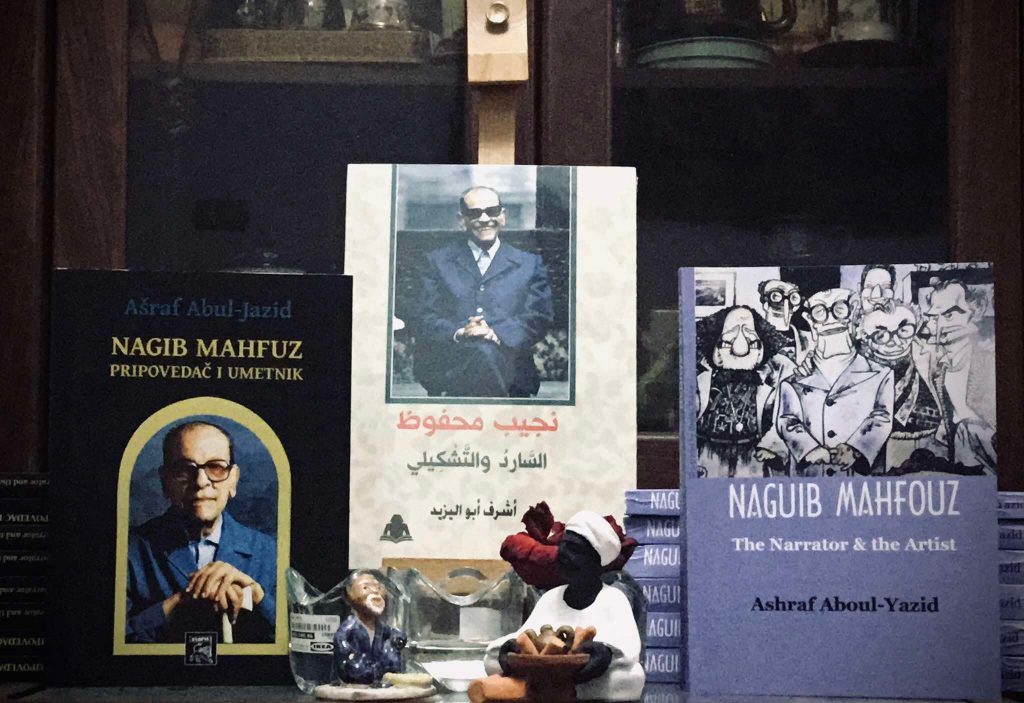

My critical and biographical works, such as The Biography of Color and Naguib Mahfouz: The Narrator and the Artist, further underline my dedication to documenting and analyzing Arab cultural heritage.

With almost 20 translated books, my impact extends across languages and continents. My books are translated into English, Persian, Sindhi, Urdu, Turkish, Azerbaijani, Korean, German, Russian and Spanish.

What is your future plan about your poetry?

My plan is to continue bridging languages and cultures, writing poetry that becomes a passport between nations.

I will also continue my project, The Silk Road Literature Anthology. The next will be Palestine, A poem Every Day.

I also aim to mentor young poets globally through translations and festivals.

In the previous BIBF we agreed, me and Chinese poet Cao Shui, author of the Epic of Eurasia to introduce his work in Arabic in the Silk Road Literature series.

What is your advice for new writers?

I also give these advices to myself. Read a lot. Read widely, listen deeply, and never silence your inner voice for the sake of trends. Be truthful. Write not to impress, but to express. Poetry is not popularity, it is presence.