The Memory of Narcissistic Luxury

In the restless moments of waiting in Cairo, I wandered between the ebbing of words and the depth of ideas, torn between the ache of loss and the demands of study and the future ahead.

I spoke to myself once, then again, then again—until I found solace in patience and summoned my unyielding resolve.

I remained in the company of my books from the moment the sun faded into an orange dusk, until the first golden rays pierced the gates of the earth.

At that hour, the prickly pear vendor would arrive, his voice rippling like waves through the city, blending with a melody both ancient and tender.

From the balcony of my hotel, I watched the city surge—its people crossing the streets in a torrent of motion and sound.

A voice reached me from a nearby café, a singer weaving nostalgia into the night, her voice repeating, “Ya Maal El Sham, ya Maali… Tal El Matal, ya Helwa Taali”.

Then, she changed the words: “Ya Maal El Saudiya, ya Habibi, ya Maali…”

And so she went on, invoking one Arab land after another, as though her voice could summon them all into her embrace.

I imagined the coins cascading upon her, the banknotes scattered at her feet, until dawn finally unfurled its golden veil over the city.

Cairo is a mystery.

A city where everything exists, where history stands aged and fragrant, where art reaches the peaks of its glory.

A city of monumental minds, where words are sacred and names are eternal.

Books line the streets, their pages fluttering like doves, and libraries stand open on every corner, their lamps glowing with the scent of ancient oil, their light woven with dawn and prayers.

Newspapers intoxicated with ornamented passion.

Cinemas that carry the weight of history.

Theaters that have witnessed legends unfold.

Masters of art, and sages of wisdom, towering figures who shaped revolutions and inscribed destiny.

Voices from Arab radios, draped in the fabric of their nations, calling for unity and dignity.

And within its hallowed halls and sacred echoes, Cairo hums with Sufi hymns, songs drenched in longing, voices that plead for the Divine, dissolving agony into a pilgrimage of love.

Here, thinkers gather, leaders emerge, and pillars of knowledge stand tall, their presence woven into the very fabric of time.

And when night falls, when the horizon dims into kohl and gold, the city comes alive once more.

Lights glitter upon the Nile, lovers gather on its shores, whispering to the moon, speaking to their souls—until the light itself smiles through the jasmine-scented breeze.

As the night unfurls its sails, voices rise from every corner, and the city swells into a wedding procession that lasts until dawn.

Time scatters into fragments, music pulls you deeper, and the soul sways to a melody that breathes of longing, art, and hope—a tribute to the Nile’s eternal song and its whispered hymns to the homeland.

And if you seek the blessing of saints, if you long for the lively clamor of Al-Hussein, you will walk with the rhythm of joy, losing yourself in the labyrinth of alleyways and marketplaces.

You will cross into Mohamed Ali Street, where instruments rest upon the pavement, soaked in melodies that are aged like fine wine, wrapped in the incense of ancient celebrations and wistful laments.

And as the night weaves its path through Khan El-Khalili, through the city’s bustling cafés, through the boats that glide across the Nile, the river carves its way through time itself.

And when history speaks, its voice erupts from the sacred dust of the pyramids, where the impossible was once achieved, where monuments stand defiant against eternity.

Here, in Cairo, the past engraves itself upon mosques and minarets, upon the echoes of ablution and devotion, upon the footsteps of those who once dared to dream.

Here, the spirit of revolution soars, whispering through the mausoleum of Nasser, where the songs of liberation still echo in the halls of memory.

And the pledge remains unbroken—a vow sworn by the spirit of revolution, the will of the people, the resilience of the High Dam, and the unshaken resolve of Cairo Tower, standing tall as a monument to history that will never fade.

At sunrise and sunset, you ride a ḥanṭūr, its wheels tracing the streets of the city, as history smiles back—a flood of meanings, alleyways, minarets, cannons, and hurried trains, all weaving the fabric of hope.

And what beauty could rival this? It is the Egyptian soul that remains the most beautiful—light of spirit, warmth of heart, and elegance of conscience.

Oh, Cairo of al-Mu‘izz, how magnificent you were, leading the East into the grand voyage of existence, soaring like a bird across the skies of Arab brotherhood, the lands of Islam, the Non-Aligned Movement, and the gathering of nations.

You move in harmony with the rhythms of Sufi hymns and the whispered prayers of Taraweeh in Sayyida Zaynab. The call to prayer rises, summoning the faithful, and the city bows in devotion.

And as night falls, you glimpse a siren of longing, selling desire in velvet-lined boxes, singing a melody whose rhythm she has already bid farewell. The air quivers with wounds set ablaze, while bouquets of roses scatter like clusters of gold.

Tourists and wanderers lose themselves in revelry, drawn to halls that tame time and ease sorrow, so that tears may finally dry.

Imagine Cairo, the city that never sleeps, pausing only for fleeting hours to embrace the dawn, to meet the call of the muezzin as life stirs once more.

Sunlight pierces through the windows, and guests begin to arrive at the dining hall for breakfast.

Suddenly, a man approaches me, a look of curiosity on his face.

“Good morning, lady of the crimson eyes.”

It is as if he had watched me with the dawn.

He introduces himself—Fayez Mahmoud, the esteemed Jordanian writer and philosopher, who worked at the Palestine Revolution Radio in Cairo, under the direction of al-Tayyib ‘Abd al-Rahim.

We delve into conversations on politics and philosophy, before I excuse myself to leave for the university.

When I return to the hotel, we meet again over lunch, and in time, he becomes both a brother and a friend, his concern for me growing with each passing day.

The hotel was filled with students and intellectuals, and there, I also reunited with friends who had come to Cairo to pursue their studies.

We gathered, bound by affection and thought, and our meetings became a cherished ritual.

It was in that very place that I also met Professor Ibrahim al-Fayoumi, who was pursuing his doctorate at al-Azhar University.

Dr. al-Fayoumi carried himself with grace and refinement, and we soon regarded him as a grandfather to us all, bound by a friendship of pure loyalty and unbroken bonds—ties that have endured to this very day.

During our many discussions, Dr. al-Fayoumi often expressed admiration for my approach in engaging with others, and he continued to do so until he visited us in Jerusalem.

There, he met my father, and as conversations intertwined, he spoke with great appreciation of my father’s intellectual philosophy—a philosophy that had shaped the path I walked with unwavering confidence.

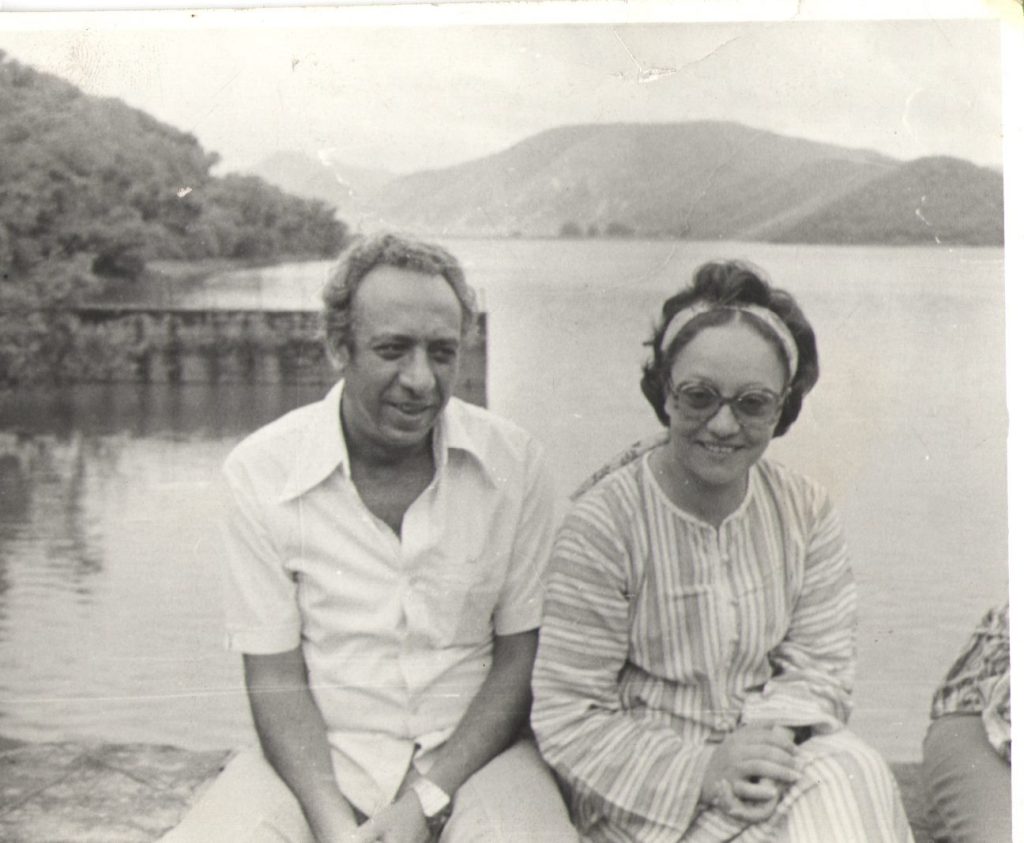

After completing my exams, I conducted a series of literary interviews with some of Egypt’s most renowned writers, alongside Fayez Mahmoud.

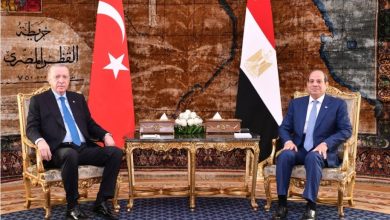

Among the most memorable were my encounters with the great Tawfiq al-Hakim and the legendary Naguib Mahfouz.

I inquired about them and learned that they sat daily at the “Petro” Café in Alexandria between nine in the morning and two in the afternoon. Determined to meet them, I took a private car, accompanied by my colleague Fayez Mahmoud. We carried our press equipment—the recorder and camera—and even brought along a professional photographer.

As we entered the café, we saw the two literary giants seated with a wooden partition between them, surrounded by a number of scholars and admirers. We took a seat at a nearby corner, observing them. It seemed that Tawfiq al-Hakim had noticed our presence—he was known for avoiding journalists. The conversation between him and Naguib Mahfouz flowed, while we pondered how to approach them.

Their discussion soon shifted to Al-Azhar University—its heritage and teaching methods. It was a golden opportunity to introduce myself. Seizing the moment, I presented myself as an Azhar student. Tawfiq al-Hakim looked at me with a smile, his face reflecting surprise and curiosity:

Their discussion soon shifted to Al-Azhar University—its heritage and teaching methods. It was a golden opportunity to introduce myself. Seizing the moment, I presented myself as an Azhar student. Tawfiq al-Hakim looked at me with a smile, his face reflecting surprise and curiosity:

“You? An Azhar student? Is that even possible? And what threw you into such a place?” he asked playfully. Then, with a mischievous grin, he quipped, “That’s not Al-Azhar—it’s Al-Aghbar!” (a play on words suggesting it was something faded or worn out).

Of course, I was dressed in modern attire that suited my personality and youth, rather than the traditional garb of an Azhar student. I responded with confidence, “I am a modern Azharite, drawn to Al-Azhar by the spirit of history and the radiance of words.” My reply seemed to amuse him, and we soon found ourselves engaged in conversation. He asked about the situation in my homeland, while Naguib Mahfouz listened on with a quiet smile.

The introduction to my interview later read:

“In the corner of Tawfiq al-Hakim at ‘Petro’ Café, where the setting overlooks a vast expanse of sea and tranquility envelops the gathering—except for the lively discussion brimming with literature, philosophy, and culture. Amid the discourse, bursts of playful banter lend an air of ease, making room for contemplation and dialogue in what has come to be known as ‘Al-Hakim’s Corner.’ I met Tawfiq al-Hakim there, deeply engaged in a passionate conversation with Naguib Mahfouz, surrounded by a circle of literary and intellectual figures.”

When I asked about the role of a writer, he responded, “In my book Under the Sun of Thought, I addressed this question: ‘Writers and thinkers are the leaders of reform; they lay its foundations and draft its blueprints in every era and place. Literature in Egypt is now moving in the right direction.’”

Regarding the role of women, he remarked, “Women have gone to university, received an education, and emerged into the streets looking elegant and refined. Yet, these same women do not know how to make a simple potato casserole. In other words, women have abandoned their femininity, forsaken their primary duty, and become preoccupied with trivial distractions.”

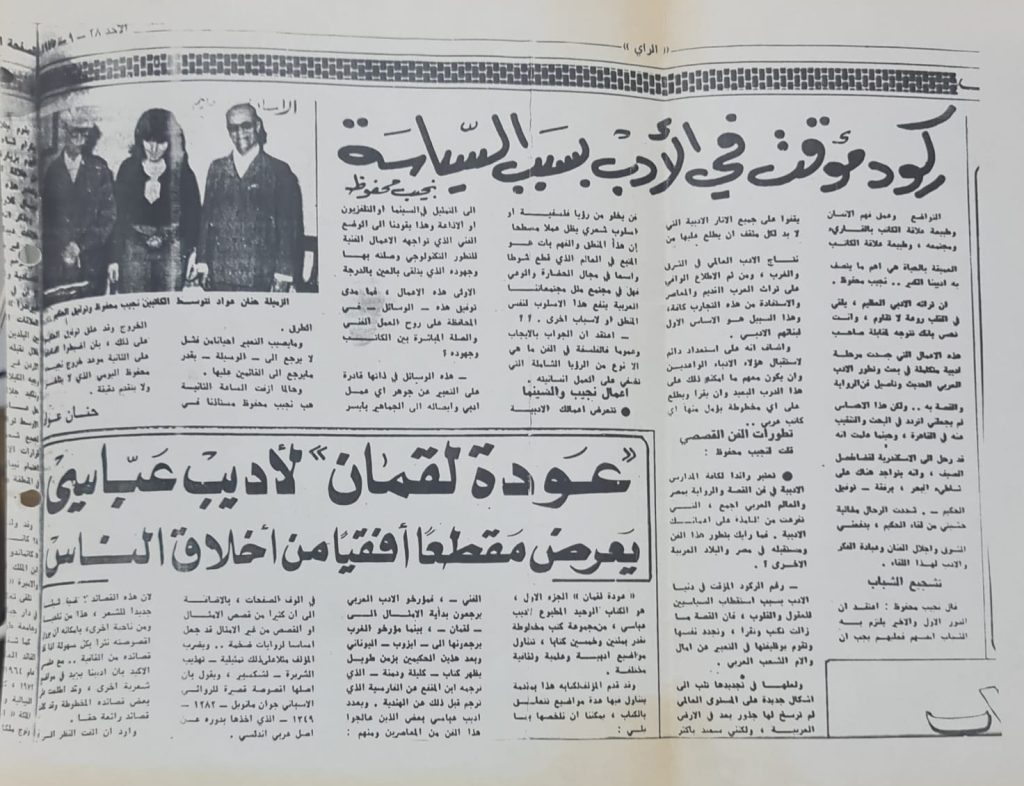

The discussion was rich and delved into significant issues, as well as an analysis of his most important works. The full interview was later published in Al-Rai newspaper in Jordan.

I continued the interview for hours while Fayez Mahmoud recorded it. Suddenly, Tawfiq al-Hakim stood up—it was two o’clock, time for his departure. He walked, leaning on his cane, and I subtly suggested to Fayez that he should embrace him on my behalf. Fayez did so, saying, “I am fulfilling Hanan’s request,” to which al-Hakim laughed and replied, “You’re the one hugging me?”

With deep respect for his wisdom and fatherly presence, I approached him, embraced him gently, and bid him farewell.

The following day, I continued my discussion with Naguib Mahfouz in the same café before returning to Cairo to pursue other interviews.

My conversation with Naguib Mahfouz was distinct, unfolding in the brilliance of thought and the delicate threads of spirit interwoven with his words. The introduction to our interview read:

“Humility, a profound understanding of human nature, and a deep connection between the writer, his readers, and society—these are among the defining qualities of our great writer, Naguib Mahfouz.”

When asked about his literary works that had been adapted for television and cinema, he responded, “These mediums are capable of conveying the essence of any literary work and making it accessible to the masses in the simplest ways. When they sometimes fail, it is not due to the medium itself but to those who handle it.”

Regarding his views on encouraging young writers, he emphasized, “It is essential for young writers to familiarize themselves with all the great literary works—both from the East and the West—as no true intellectual can be without this foundation. Additionally, they must have a deep and thorough understanding of classical Arabic literature, which is the fundamental pillar of their literary formation. With these conditions met, I am more than willing to encourage and support them.”

Our discussion extended into philosophical and political themes, unfolding as a profound historical and cultural dialogue—a reference point for those seeking knowledge.

At the renowned Riche Café, nestled in the heart of the city, the laughter of distinguished writers once echoed, and the pages of their luminous works found their beginnings. A simple café, its walls adorned with portraits of brilliant literary figures—those who carried the torch of words and left behind a legacy. Simple chairs, inside and out, bore witness to conversations of the hour, to poetry and song.

It was there that I met the esteemed Egyptian critic, Farouk Abdel Qader, a strikingly handsome young man who held his cigarette or pipe with a touch of pride and defiance. An intellectual bond formed between us, and I came to cherish his friendship. Our encounters were sporadic, taking place at book fairs or cultural conferences. We engaged in long discussions about literature and criticism, and he once posed the question of the intellectuals’ crisis, saying, “The nature of the ruling systems in our societies does not respect culture.” He then delved into answering my questions with remarkable eloquence.

We then made arrangements to meet the poet Amal Dunqul. That evening, we went to Riche Café, where Amal was seated with a foreign woman and several other writers. We approached, introduced ourselves, and soon found ourselves deep in conversation about literature and politics. When the other writers departed, I began my interview with him.

Amal—or rather, Muhammad Amal—was an intriguing and somewhat enigmatic figure. When I started speaking with him, he spoke in an almost inaudible whisper, forcing me to lean in closer to hear him. Realizing the game he was playing, I pulled back and quipped, “That’s an old trick.” He burst into laughter and remarked, “That’s Egyptian wit for you.”

As our discussion deepened, he spoke candidly about the Arab world, saying, “Poetry was an alternative to suicide, especially in the years between 1967 and 1972. When one is confronted with such darkness and disgrace, the first instinct is either to kill, be killed, or explode in rage. For me, poetry was the only way to maintain balance between the self and the world. My concern with national issues was a result, not a premise. Between ’67 and ’73, poetry replaced suicide. That was evident in my first collection, Mourning Before Zarqua’ Al-Yamama.”

When asked about the significance of poetry in the Arab world, he responded, “Words are weapons, but they do not strike down enemies or demolish fortresses. Yet, words are the primary tool for transformation in any society. No civilization can be built without a philosophical foundation. When civilizations lose the power of words, they enter their twilight years.”

The dialogue was profound, touching on many crucial issues, and he responded with a vibrant and illuminating style.

When the interview concluded, the three of us strolled along Fouad Street before stopping at Bab Al-Louq Café, where the conversation took an unexpected turn. He began asking me personal questions I had never encountered before—questions that unsettled me, stirring a deep sense of modesty. I was taken aback by the nature of his inquiries, which had never crossed my mind nor fit within my perception of things. My face flushed with an unusual shade of red. Embarrassed, I politely excused myself, ending the meeting, and returned to my hotel to continue writing.

The following day, he sought me out to apologize, acknowledging my perspective. From then on, mutual respect flourished between us. Our friendship grew, and those previous questions faded away, replaced by discussions on philosophy, culture, and politics.

The next day, I visited the poet Salah Abdel Sabour at his office overlooking the Nile. He radiated energy and seriousness, and we spoke at length about the sorrows of our wounded homeland. We met several times afterward, and I still recall his solemn demeanor and deep, reflective dialogue. I admired his intellect and spirit.

Under the title, “Salah Abdel Sabour: A Man Burdened by Ideals, Freedom, Truth, and Justice,” our conversation was later published in Al-Rai newspaper in Amman. During the interview, he explored the evolution of the poetic movement, the civilizational crisis, and literature’s role in it all. He also shed light on his personal struggles, stating:

“My struggles, or rather my wounds, have always been the wounds of values—of ideals in our modern societies. They are the wounds of freedom, justice, and truth. By freedom, I mean both spiritual and physical freedom. By justice, I mean justice on both an individual and societal level. And by truth, I primarily mean man’s honesty with himself, then his honesty with his reality and with others. A review of my poetry and plays might reveal to critics just how deeply I am connected to these three values.”

In the office across the way, I met the esteemed critic Rashad Rushdi. We engaged in a deep conversation about literature and theater, capturing several historic photographs together. He possessed both vast knowledge and a lighthearted spirit that infused our dialogue with a rich human and cultural depth.

I feel a profound sadness as I write about these towering figures—people I once knew, who have since departed, yet still live within me through their words and their presence.

My interviews found their way onto the pages of prominent newspapers: Al-Ra’i, Al-Quds, and others. Memory, ever restless, knocks on the doors of time, longing for past encounters as the remnants of those moments are scattered like dust across the crushed hours. I am often taken aback when my thoughts drift back to those days, and I find myself once more lost in the endless loop of contemplation. My madness returns, compelling me forward on the endless journey of the written word.

The following day, I visited Akhbar Al-Youm newspaper to interview the renowned theater critic Sami Khashaba. A young man brimming with energy, he moved with restless enthusiasm. We met at the newspaper’s headquarters and delved into discussions on literary criticism and modernism. Afterward, he invited me to lunch at a humble restaurant in Al-Hussein, where we sat in an intimate setting, steeped in Egyptian warmth.

Amidst the movement of people and the boundless expanse of the city, I felt as though I had stepped into a new human realm—one that gifted me deeper insights, compelling experiences, and a heightened sense of awareness.

During our conversation, he shared his vision of the writer’s role in political and social struggle, drawing from his own experience of imprisonment:

“Since literature is a committed form of expression, a writer must engage with political activism—not necessarily as a direct participant in the political field, but through their literary works, which must not overlook these crucial issues.”

He cited Naguib Mahfouz as an example and went on to discuss the state of Palestinian poets, praising their literary contributions and global influence. He regarded resistance literature as a transformative force in Arab consciousness, stating that through literature, the Palestinian cause had gained a universal human dimension in its struggle against occupation and adversity.

I spent countless hours wandering the chaotic streets of this magnificent city, walking through its thoroughfares in both morning and evening. I observed the bustling cafés, sometimes stepping inside to sit among the people. Often, I found myself engaged in conversation with a retired general or a writer just beginning his memoirs.

I had grown accustomed to visiting Bab Al-Louq Café, where I encountered a number of Egyptian intellectuals—people of immense kindness and wisdom. From them, I learned much, and about them, I wrote much.

It was during this time that I had the privilege of meeting the great Iraqi poet Abdul Wahab Al-Bayati. This encounter included my brother Riad, who was in Cairo at the time—an intellectual of profound depth and artistic vision. Together, we discussed poetry, the role of women in literature, and themes drawn from Al-Bayati’s experience of exile. His poetic philosophy left a lasting impression on me, and I absorbed much from his school of thought.

When I asked him about Palestinian literature, he responded with conviction:

“The Palestinian revolution, the true flame of the forthcoming Arab awakening, has enriched Arab consciousness and modern history with invaluable experiences. The Palestinian people, having emerged from the depths of tragedy, possess an unmatched ability to articulate the aspirations of revolution.”

He spoke at length about Palestinian literature with remarkable depth and passion. Our conversation then expanded to include global literature and the evolution of women’s writing.

That day also happened to be my brother Riad’s birthday. When I mentioned this to Al-Bayati, he insisted that we celebrate the occasion in the evening.

That night, he visited us at our hotel, and we were joined by retired General Sadiq Ghanem, whom I had met earlier. Together, we stepped out for a stroll along Fouad Street and the nearby alleyways before heading to Alfi Restaurant for dinner.

After finishing our meal, we took a leisurely walk, when suddenly, the general hailed a hantoor—a traditional horse-drawn carriage—and invited us aboard. As we rode through the city, he launched into an impromptu celebration, singing birthday songs that we all joined in. He then serenaded us with the classical melodies of Abdel Wahab, filling the night with a nostalgic and enchanting rhythm.

It was an unforgettable evening—one that brought immense joy to my brother and to all of us.

When the time came to part ways, I bid farewell to the general and our esteemed poet.

Years later, I met Al-Bayati again in Amman.

As for the general, I never saw him again.

I also met the painter Mohammed Kandil, the writer Anis Mansour, the playwright No’man Ashour, the poet Mohammed Ibrahim Abu Senna, and the short story writer Ibrahim Aslan. We had significant and lengthy discussions that were published in several Arab newspapers.

While I was immersed in these creative meetings, my father grew worried about me, so he sent my brother Riyad to Cairo once again to bring me some money, just in case I needed it. The truth is, he had already given me enough, but the boundless concern and affection of parents surpass all considerations.

My brother asked about me at the hotel, but did not find me. Then he went out to eat, and as I was walking down Fouad Street, I suddenly saw him there. I rushed with joy to meet my dear brother, who was also trying to submit his papers to Cairo University for admission. The university asked us to obtain a supporting letter from the office of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).

The next day, we went there, accompanied by the writer Fayez Mahmoud, who, as I mentioned before, worked at the Palestine Revolution Radio. We met the representative, explained what we needed, and he replied: “This is an easy process. You need to get a letter from the organization’s representative in Amman, whose name is Bahjat Abu Gharbia, along with a transcript and all the required documents.”

Hope was restored to us, especially since my brother had achieved an excellent grade in his secondary school exams. We left the office filled with happiness and returned to the hotel. Shortly after, I said to my brother: “I’ll be gone for a little while.” I went out, headed to the airline office, and asked if I could buy a plane ticket to Amman for a day trip. The answer was yes, so I bought the ticket and flew to Amman that evening.

I arrived there, went to the Caravan Hotel in Jabal Al-Weibdeh, and the next morning, I visited the honorable fighter Bahjat Abu Gharbia. He welcomed me warmly and gave me the required documents with great generosity. I left there overjoyed, booked a flight back that afternoon, and returned to Cairo.

When I reached the hotel and looked for my brother, he was not there. I called the Palestine Radio station but found no one, which made me lose hope. An hour later, I went out walking on Talaat Harb Street, glancing left and right. Suddenly, I saw my brother Riyad walking with Fayez Mahmoud ahead of me. I shouted, and my brother collapsed to the ground in shock, unable to believe I had returned so quickly. He even asked for my passport to make sure, and we laughed a lot before continuing with the procedures.

The next day, I went to the PLO offices and submitted all the required documents. They seemed surprised, not expecting me to bring everything so quickly. I left, waiting for the acceptance. As I reached the door, one of the brothers from the office, whom I believe was the legal advisor, stopped me and said: “Don’t get your hopes up too much. I don’t see much interest in the matter.” I respected his honesty, thanked him, and left with many questions swirling in my mind: “Why can’t honesty and integrity be the basis of all human and political dealings? How can efforts be wasted in vain for whims and interests that might never come to fruition?”

This experience was the beginning of my understanding of matters I could neither grasp nor accept: “Why didn’t they apologize from the start and save me the effort I put in? Isn’t a sincere apology better than false promises that I took seriously and fulfilled their conditions?” This was the first shock I received from an official institution that represented us and that we took pride in.

I crossed Cairo’s skies, heading back to my homeland. Upon reaching Amman, I contacted Al-Ra’i newspaper and arranged an appointment with the editor-in-chief at the time, Mr. Suleiman Arar. We scheduled a meeting.

When I met him, he turned out to be a cultured and courteous Jordanian man, with eyes that spoke with encouraging warmth. He looked at the interviews with appreciation and admiration, giving them a prominent place in the newspaper. He first published my interview with Tawfiq al-Hakim, which received wide acclaim. I got used to meeting him, handing him the weekly interview, and then heading back across the sad bridge, returning to the spirit of the beginning in my homeland.

He surrounded me with special care and showed great interest in my interviews.

Thus, moments pass through their chronological path, and words travel from them and with them, racing with the speed of lightning and sound, to remain in their circular orbit.