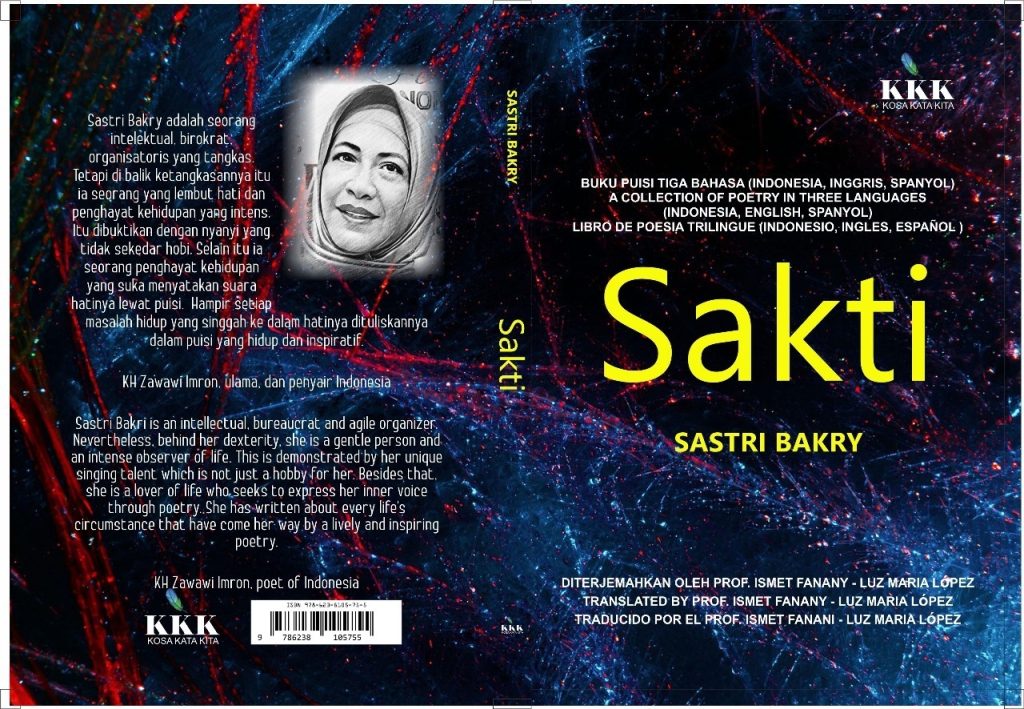

Sastri Bakry’s Sakti (2025) is a collection of thirty-seven poems that merges themes from personal memory, social conscience to spiritual sensibilities. Originally composed in Bhasa Indonesian, this collection offers the English and Spanish translations of the poems. Professor Ismet Fanany from Indonesia and Puerto Rican poet Luz María López has rendered them into English and Spanish respectively.

Bakry is one of Indonesia’s most prolific and multidimensional literary figures, whose career spans fiction, poetry, activism, and public service. Founder of Sumbar Talenta and the Teras Talenta Reading House, and currently serving as Chairman of SATUPENA West Sumatra, Bakry’s voice in Sakti emerges from a life deeply intertwined with literature, politics, and community engagement. A former politician and senior bureaucrat in the Ministry of Home Affairs, she brings to her poetry a seasoned understanding of governance, social justice, and civic responsibility.

Sakti carries the weight of these experiences: its poetic voices shift between the nurturing mentor, the unflinching social critic, the custodian of cultural memory, and the contemplative believer. Bakry’s poems fuses personal witness with public conscience where the intimate and the national, the local and the global, coalesce into a distinctly Indonesian moral vision.

Nurturing and Moral Formation

Poems such as “My Kind Teacher” (pp. 3–4) and “Sakti” (p. 91) portray education and upbringing as deeply moral acts, shaped by patience, discipline, and unconditional love. In “My Kind Teacher,” the educator is both guide and guardian, “rooted in feelings / Standing strong, even when storms come” (p. 3). The poem layers the schoolyard’s playful energy with the gravitas of moral teaching, presenting teachers as banyan trees—symbols of protection and moral rootedness in Indonesian cultural imagination. The title poem “Sakti” shifts the focus to maternal love, revealing a poignant adoptive bond. The son, now grown, thanks his mother for being “hard on me” because without discipline, he “would not have grown up to be like this” (p. 91). The mother’s love—”planted by God”—transcends biological ties, aligning with the Javanese and Minangkabau ideal that care and kinship are defined by devotion, not bloodline. Both poems embody Sakti’s humanistic belief that strong character is cultivated through a blend of compassion, discipline, and moral example.

Social Justice and Corruption

A sharper, satirical edge emerges in “Come, Close Your Eyes” (p. 75) and “We Are Different” (pp. 79–80), which confront structural injustice and public complacency. In Come, Close Your Eyes, the repeated imperative invites readers to witness—and then ignore—abuses of power: “To the sale of narcotics by high-ranking police… To the official that proudly takes an illegal second wife” (p. 75). The refrain works ironically, critiquing both corrupt officials and the societal habit of looking away. “We Are Different” contrasts the opulent excess of the elite—“One piece of cake could be ten meals of rice for my children”—with the poet’s memory of life “at the bottom of the wheel” (p. 79). The juxtaposition of highland beauty with the riverbank’s earthy scents highlights the enduring gulf between rich and poor, even as the speaker affirms that “Our enjoyment is the same / It is only status that distinguishes.” Through these poems, Bakry gives poetic form to everyday experiences of inequality in Indonesia, showing how structural privilege and poverty coexist in uneasy proximity.

National Memory and Sacrifice

Patriotism in Sakti is tempered by tragedy, especially in “In Deep Depths” and “Remember Us” (pp. 30–31), which memorialize the sinking of KRI Nanggala 402. Here, the ocean is both workplace and grave: “Fifty-three people / We present to you the motherland” (p. 30). The high “hydrostatic pressure” becomes a metaphor for the physical and moral weight borne by those serving at sea. The companion piece “Remember Us” appeals to the living to “run on a straight, just and civilized path” (p. 31). By merging the voices of the dead with a call to civic virtue, Bakry transforms an incident of national mourning into a moral charge for the future.

Nature, Faith, and Moral Endurance

In poems such as “I Long to be Like the Olive Tree” (p. 41) and “A Raintree” (p. 106), Bakry uses natural imagery to reflect on spiritual and ethical steadfastness. The olive tree—Qur’anic symbol of blessing—is praised for its longevity and generosity: “Nothing of it is wasted… the older you grow, the richer your gifts” (p. 41). The speaker’s wish to “be like the olive fruit” frames moral endurance as a lifelong aspiration. “A Raintree” blends environmental and social responsibility. The tree “protect[s] those who take shelter” and continues to “draw calm water” despite age and damage, becoming a model for resilience in community life (p. 106). Both poems affirm that moral strength, like the rootedness of trees, comes from stability, care, and the ability to shelter others, echoing Indonesian values of gotong royong (mutual support).

Sakti offers a vision of life where care, justice, sacrifice, and moral steadfastness are the pillars of individual and national integrity. Sastri Bakry’s most resonant works draw strength from Indonesia’s cultural and religious imagery while addressing contemporary issues—from corruption to environmental degradation, from social inequality to maritime tragedy. Her poetry invites readers not only to remember and reflect but also to act—to root themselves like the banyan and olive, to open their eyes to injustice, and to carry the memory of sacrifice into the work of building a just and compassionate society.