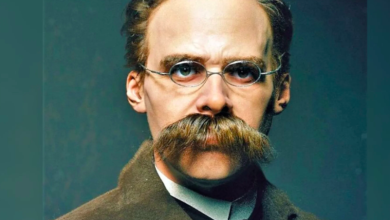

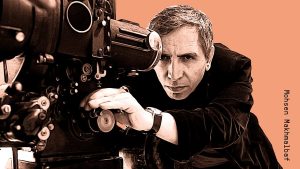

The deteriorating conditions of the peoples in the Middle East have always concerned the cinematic family of Mohsen Makhmalbaf. His wife, the distinguished director Marzieh Meshkini, has presented notable films that reflect the oppression and injustice faced by Muslim women in general, and Iranian women in particular, such as The Day I Became a Woman and The Day I Was Born a Woman. These films boldly address the injustices inflicted upon women under Islam and its harsh laws.

Their son, Maytham Makhmalbaf, works as a cinematographer and editor. He performed both roles in his father’s 2012 film The Gardener, and he also directed Backstage and other films.

Their daughter, the young director Samira Makhmalbaf, made her first film, The Apple, in 1998 at the age of eighteen, becoming the youngest director to compete for the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. The screenplay was written by her father, based on a novel by Simin Daneshvar and poetry by Forugh Farrokhzad. Though Iranian censors did not approve the film, Samira participated in Cannes, where the film won the Caméra d’Or unanimously. In 2000, she presented Blackboards, which also won the same award at Cannes. She also directed At Five in the Afternoon.

Hana Makhmalbaf, another talented director in the family, made her first feature film Buddha Collapsed Out of Shame, inspired by the Taliban’s destruction of the giant Buddha statues in Bamiyan. She co-wrote the screenplay with her mother, Marzieh Meshkini, at the age of eighteen. The film was shown in international festivals and received a special award at the Berlin Festival in 2008, as well as a special award from the San Sebastián Festival in Spain that same year.

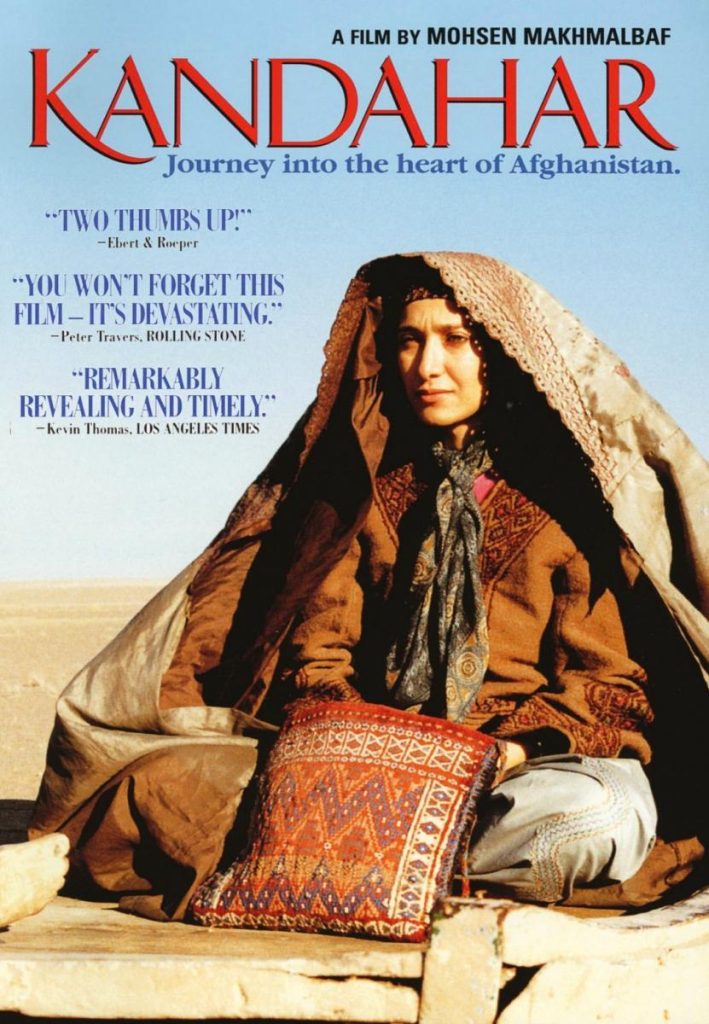

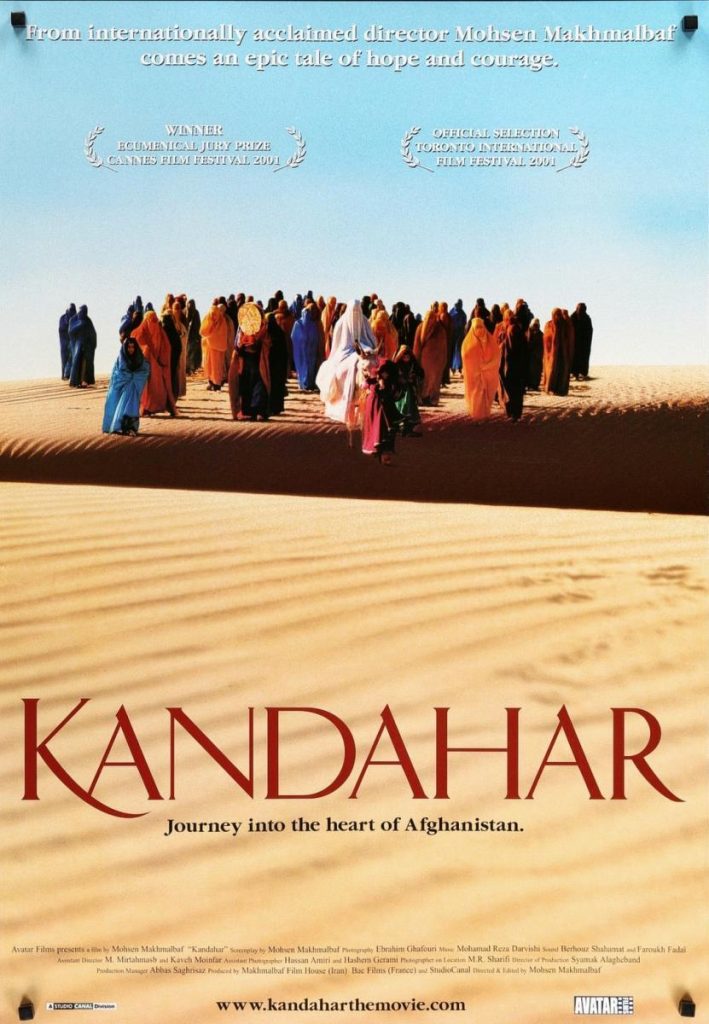

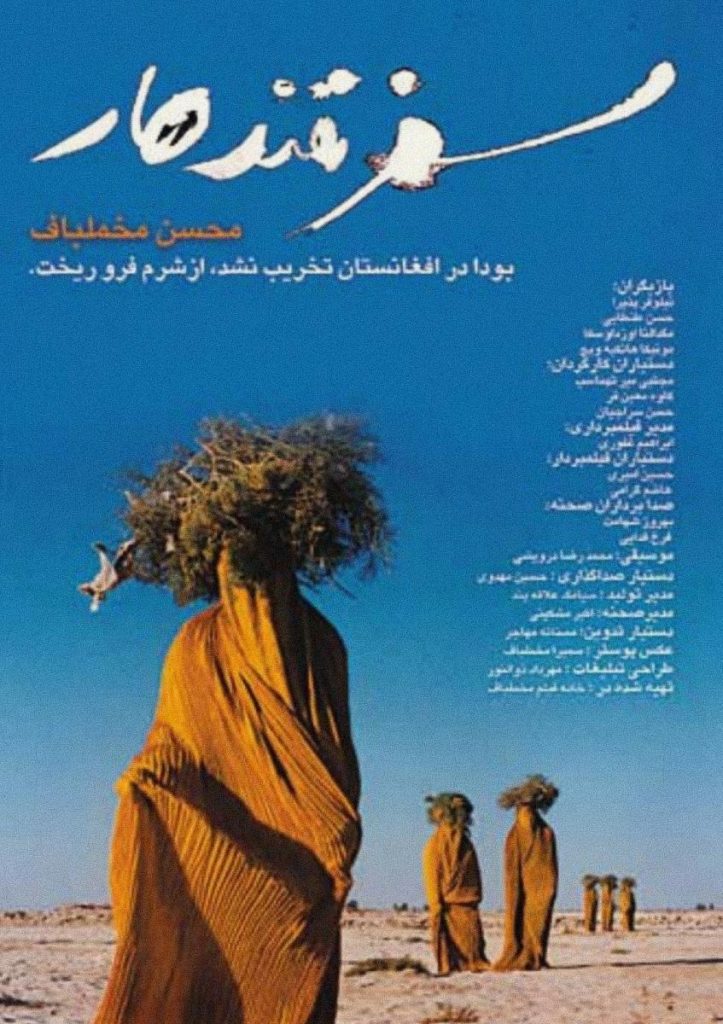

- Kandahar posters in Persian and English (3 photos)

Twelve Years Between Kandahar and The Gardener

“I’m not a religious extremist, but it’s impossible to ignore the religious factor and its energy, and to view problems solely from a secular perspective… Hatred in the name of religion and peace in the name of religion are two very important topics. Perhaps next time, I’ll make a film about Zoroastrianism,” said Mohsen Makhmalbaf about his film The Gardener during the annual Jerusalem Film Festival in July 2013.

The Gardener was filmed in Haifa’s famous Bahá’í Gardens, surrounding the global center of the Bahá’í faith. Makhmalbaf added: “I chose the Bahá’í faith because of its tolerant and non-violent philosophy.”

The film won Best Middle Eastern Documentary at the 2012 Beirut International Film Festival. Its world premiere was held in Busan, South Korea. In a recorded message for the Beirut festival, Makhmalbaf stated:

“I dedicate my film to everyone working for peace among religions to stop the wars destroying our world in the name of God.”

As for Kandahar, which won the Ecumenical Jury Prize (granted outside the official competition) at the 54th Cannes Film Festival in 2001, it was originally titled The Sun Behind the Moon. The film depicts the tragic situation in Afghanistan caught between civil war, landmines, poverty, and drought. It opens with a young Afghan-Canadian journalist who fled the horrors of war, receiving a letter from her younger sister in Kandahar—who lost her legs to a landmine—announcing her intention to end her life on the day of the final solar eclipse before the dawn of the 21st century.

The Afghan protagonist wears a chador, pretending to be the fourth wife of an Afghan man, with only three days left to reach Kandahar before the eclipse. Makhmalbaf conducted extensive research for the film.

Between the Shah’s Regime and the Islamic Revolution

Under the constraints of both the Shah’s regime and the strict Islamic rule that followed the 1979 revolution, Mohsen Makhmalbaf was unable to fully realize his artistic vision. At 17, he took part in protests against the Shah and was imprisoned for a year and a half. After the revolution, the Iranian state strongly supported film production, establishing the Farabi Cinema Foundation in 1981. Taxes on film production were reduced, but this support aimed to use cinema as a tool for public mobilization during the Iran-Iraq war and to export the Islamic revolutionary ideology.

In 1982, Makhmalbaf directed his first film, Nasouh’s Repentance, followed by The Blind Eyes and Escape from Evil to God—films that aligned closely with the state’s revolutionary messaging.

By 1985, however, Makhmalbaf shifted away from the clergy’s influence, directing his first true cinematic work Boycott, a personal narrative about an Iranian leftist (Faleh) pursued by intelligence officers after his release from prison, where he was tortured for trying to stab a policeman. In prison, he meets revolutionary youths resisting the Shah’s regime and begins re-evaluating his beliefs. The film starred Majid Majidi, later known for Children of Heaven and The Song of Sparrows.

This new direction, however, did not please the authorities, and censorship tightened. Many creative filmmakers who continued presenting critical visions of post-revolution Iran eventually chose exile, seeking artistic freedom. The Makhmalbaf family was among them.

They filmed The Gardener, inspired by real events, using non-professional actors.

Cannes and Beyond

Makhmalbaf participated in the Cannes Film Festival several times with films such as Time of Love, Salaam Cinema (1997), Gabbeh, and in 1999, he competed for the Palme d’Or with The Legend of the Army of the Sleepers.

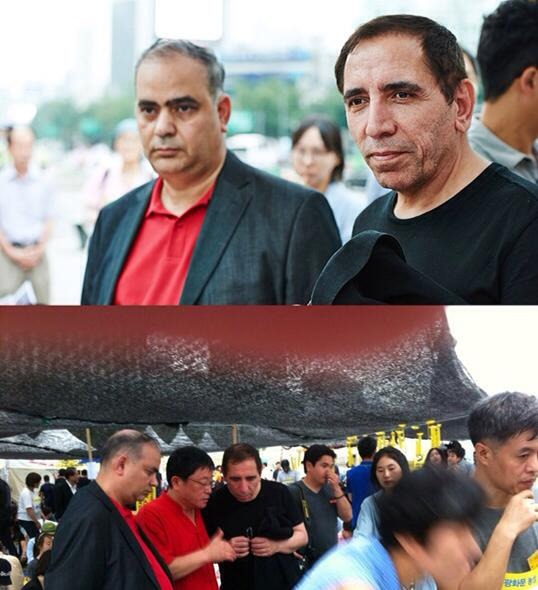

The Manhae Prize for Arts in Honor of Makhmalbaf’s Creative Mission

On August 12, 2014, Makhmalbaf received the Manhae Prize for Arts and Creativity at the Inje Cultural Center in Gangwon Province, South Korea. The award is named after the Buddhist monk, poet, and activist Han Yong-un (1879–1944), known by his pen name Manhae. It is a global prize awarded in literature, art, community service, and peace. Makhmalbaf was selected for his rich and impactful journey in art and peace. In the year the Egyptian poet Ashraf Dali has been awarded the Manhae prize in literature.

The value of cinema as a tool for reform, awakening thought, and promoting peace, love, and a sense of belonging—while engaging both mind and heart—is vividly and poetically embodied in the works of the great artist Mohsen Makhmalbaf.

Published in CAJ International Magazine | May Edition