By Rosella Nicolló, IL SAGGIO Monthly Cultural Magazine, Year XXIX, No. 350, June 2025, pp. 18-19. Translated into English by the Spanish poet Virginia Fernández Collado

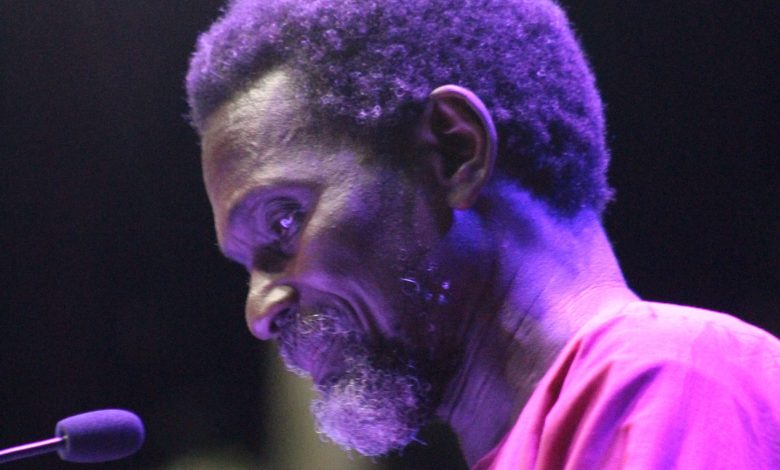

ISMAËL DIADIÉ HAÏDARA

(13)

Through the window, the desert calls me.

The silence is so great without the falling shells.

(14)

Before exile, I had a house.

In the garden, smoke rose from meat and laughter.

(21)

I had a library, a garden, a tortoise.

The war has come, and I wander between memory and the roads.

Overcoming the temptation to read these verses only as pages from an exile diary, as traces of an autobiography handwritten on scraps of paper, in notebooks, in the margins of documents, requires a close observation of an interior landscape, with its symbols, its melancholic charm, and listening to a cry of resistance, of struggle on behalf of many uprooted peoples, whose culture is at risk of disappearing.

I’ve already spoken about Ismaël Diadié Haïdara (https://www.satisfiction.eu/ismael-diadie-haidara-inedito-ci-vuole-la-notte-perche-le-stelle-brillino/), as I translated excerpts from this extraordinary work (TEBRAE, Editions La Sahelienne), which is awaiting its full translation into Italian, and which is rooted in a wholly feminine tradition. The “tebria” is a two-line poem, generally composed in Hassaniya by desert women, between southern Morocco, Walata, Tishit, Wadan, and Timbuktu. It is in this poetic form, typical of desert women, that Ismael wrote these poems without strictly adhering to the meter and rhyme that traditionally characterize these compositions. He compiles these poems, written during his years of exile, between 2011 and 2021, in a single volume. Ismael says:

In this changing world where we are all transits of desire, journeying from country to country, from city to city without stopping definitively anywhere. In the poems I write here and there, I do not paint this world through which I am only passing, but I paint myself in the world, and thus I can tell the reader, my traveling companion, that I have fully expressed myself in this book.

Son of the desert silence, fisherman of the stars, solitary traveler with his cloak and his saddlebag, happy in his solitude while contemplating the flight of the herons, Ismaël Diadié Haïdara, a cultured and refined writer and scholar, a polyglot lecturer, was born in 1957 in Timbuktu, an ancient city in the north of the state of Mali. He is the last descendant of Ali ben Ziyad al Kuti, a citizen of Toledo expelled from the city in 1468 for religious intolerance. Fleeing into exile, he managed to bring with him and save a collection of very important documents in Hebrew, Arabic, and Spanish that constituted his personal library. After his death, his family settled permanently in Timbuktu. Over the centuries and generations, this original collection has experienced numerous vicissitudes (see Florence Quentin’s “L’esprit des Lieux – d’al-Andalous à Tombouctou – le fabuleux voyage des manuscrits Kati”), making it the latest heir to the Kati Collection, a repository of Arab-Andalusian, Jewish, Castilian, and African memory (https://tombouctoumanuscripts.uct.ac.za/manuscript-libraries/fondo-kati). In 2012, when the city was handed over to Islamic militants, Ismaël was forced to flee Timbuktu, taking his memory and his manuscripts with him. During his exile, on his travels around the world, the author composed his tebrâ, full of harmonious suggestions, with a poetic voice as powerful as rock music, reviving an ancient tradition in a contemporary key and renewing it with a style that oscillates between delicate, sad, and ironic tones. The language is fluid, close to speech, simple and clear, linked to reality, as are his own poetics and hedonistic philosophy (inspired by the Khayyam school of Timbuktu). As Martial wrote in Epigrams, X, 4: “Non hic Centauros, non Gorgonas Harpiyasque | invenies, hominem pagina nostra sapit,” or: “Here you will not find centaurs, gorgons, or harpies: my page has the flavor of man.” Thus, in Thebrae, both in the intentions expressed in the introductory section and in the verses, man shines through, Ismael who is drawn in the world, who makes the landscape converse, who loves and laughs at death:

(1203)

One day the grass will grow over my grave, but do not weep.

Floating cloud, I have laughed at everything.

From the desert rises like a flame of fire, his voice speaking to us of the simplicity of life, where love, the arcane beauty in the spurious and unpredictable presentation of existence, is light, fullness of humanity, peace and strength, surprise, enchantment, horizon, supplement of wings toward freedom.

(549)

I sing to you in my African language where the woman adorns herself with leaves.

Naked women covers yourself with light and the gaze of your beloved.

His purpose is to continue wandering, loving, sleeping, lying at night before a starry sky, looking death in the eye, learning to live in the moment, appreciating the intensity of existence in the measure and awareness of the present, molding the world like clay. The desert is not a geographical place. The desert is, above all, an experience of the human heart.

(141)

Only those who believe in nothing can enjoy everything.

Beauty exists for those who have crossed t