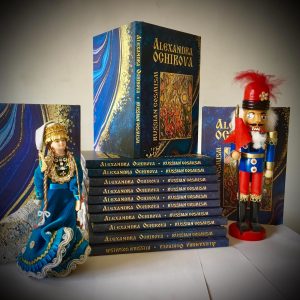

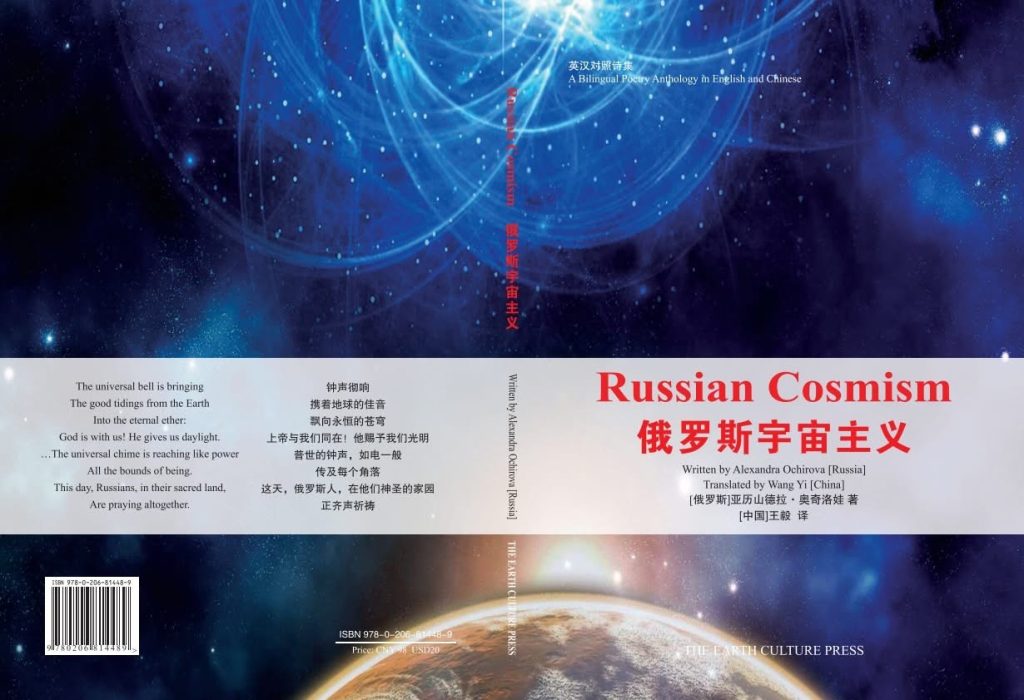

Alexandra Vasilievna Ochirova is a poet, Doctor of Philosophy, full member of the Russian Academy of Arts, UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador, Co-Chair of the General Council of the Assembly of the Peoples of the World, and Co-President of the nationwide movement “For the Preservation of the People.” She was born in the village of Perevles, Starozhilovsky District (Ryazan Region). Author of more than thirty books, including collections of poetry such as In the Beginning Was the Word, A Flight Over the City Together, A Confession Flies Over the Domes, My Horizons, Russian Cosmism, and others. Ochirova’s poetry continues the tradition of “Russian Cosmism” developed by the poets of the Silver Age. She lives in Moscow.

Reading, cosmism, poetry — themes central to the Russian soul: unity with nature, communion with God, and the quest for the meaning of life.

Recently, Alexandra Ochirova presented her new book The Oath, dedicated to the 80th anniversary of Victory in the Great Patriotic War. On the Russian soul and song, on the impossibility of canceling any culture, on the multipolarity of the world, and much more, Marianna Vlasova and Andrei Yavny spoke with her.

– Alexandra Vasilievna, tell us: how and when did poetry first enter your life?

For instance, Alexander Timofeevsky recalled that as a child he listened to verses from under the table and soon began composing himself. How was it for you?

– For me, poetry was there from birth.

It came to me as image and melody. In ordinary speech I sensed a kind of acoustic fluidity that left a deep impression. Since I learned to read very early—at the age of five—I remember how poetic form, the rhythm and imagery, opened an additional dimension of perception for a child discovering the world. My first encounter was Pushkin’s “By the seashore stands a green oak tree…” My daughter and granddaughters also learned this very poem first.

Everything connected with poetry is a mystery: the beauty of sound, the image that comes alive and changes with time. These things are remembered for life. At that age I had no particular knowledge of musical culture, but when I took part in neighborhood contests—who knew more songs or had read more books—I would improvise rhymes to a familiar tune, creating verses on the spot, and would emerge the winner.

My grandmother, who raised me, was astonished: “How is that possible? You only know one song, Two Shores!” And I explained to her honestly how it was done. After that came several books of verse that also stayed with me. From the very beginning I was drawn to mature poets and the themes they raised.

– Which themes?

– Philosophical ones.

Questions like: What is the world? Where did it come from? The stars—how can one reach them, and who dwells there? In our home there were icons and burning candles, so I was always drawn to the world in its wholeness, to man as he is. Over time, the themes never changed. They are questions without final answers.

You can study the world and man, but in the ultimate formula there remains the unknown—something belonging only to the Absolute.

– Your new book speaks of the memorable events of our country, and of the people who defended it. Why was it important for you to dedicate it to this theme?

– It is a special dedication, a collection that includes both new poems and works drawn from my earlier books. The themes in this new collection are not accidental. They have lived within me ever since I first learned all I could about the war. My mother and two of my uncles also fought; one of them fell near Rzhev. My mother was a sniper, my father reached Berlin.

There is something unspoken in the decoding of those mysteries that dwell within a person, including the DNA that is passed down through generations. If character can be inherited, then why not patriotism as well?

Many people ask why I write with such emotion. I simply cannot live otherwise. For me, patriotism is not a contrivance, not a slogan—it is a living truth.

The Russian person is, above all, soul. Hence the notions of “the most enigmatic people” and that “Russia cannot be grasped with the mind.”

I once wrote: No one invented God. He exists. Eternal good in every dimension. Not everyone is given to know, but everyone is given to feel.

– The word “patriotism,” it seems to me, has recently lost its former power. In your view, how can society’s attitude toward it be changed?

– I would not say so. It is something so deep, with formative elements woven into the very system of life. But it is true that a shift of values has taken place—from one set to another, utterly alien to the identity of the people who have lived here for centuries.

In my opinion, the spheres that give meaning are culture, education, and science. And information, which must be guarded, for in the digital space an entirely different reality is being created. The Word, in my view, is the most essential force in culture, the one that, along the vertical of history, has filled and uplifted humanity. For this reason, I give priority to literature.

– In your poetry, the themes of love for the homeland and of faith are deeply intertwined. For example, in The Iron Knight you write:

“Hope of salvation and of bliss / In solitude with truth and trial… / To look through the window and listen to one’s heart. / To feel the prayerful calm / A righteous man or sinner forgotten by all…”

How does this appear in your poetic imagery?

– As the Bible says, man sees only as much as he is given to see. I never invent anything—I write only of what lives within me. I take it “from myself,” giving preference to philosophical poetry.

Borderline situations compel a person to concentrate, to reconsider all that is happening.

– A philosophical view of the world and its phenomena is indeed a hallmark of your poetry. Your heroes “see into the root” of existence, seeking “the harmony of worlds and the illumination of reason,” yet face earthly trials such as passions and the “mirrors of deeds.” In your poem Incommensurable Losses… there appears also the image of words that “possess the power to torment and become like stones.” Is this a reflection of biblical themes, or something else? What is at stake here?

– My poetry truly is of a philosophical nature. Reflection cannot be separated from it. Of course, one can rhyme anything, but the themes I bring to people in my lectures and academic works are the same that I carry into poetry. Poetry conveys meaning more swiftly, for it always speaks in the first person. And a poet is born only when God so wills it.

I believe that poetry, particularly the ancient poetry that was foundational, created those platforms of meaning that have been handed down through time. This connects both with the earthly human being and the cosmic one, for man is not only a biosocial creature but also of the earth and of the cosmos. As Vernadsky once said, even a rain puddle on earth cannot exist without the participation of the cosmos.

– “In Russian songs there is a daring resonance / High notes that tear the voice to hoarseness. / Love and pain.” Poetry has often been bound to song, which reflects the major stages of a human life—birth, becoming, death. Tell us, what does song mean to you, and what role does it play in your work?

– As someone who possesses what is called an inner ear—at least, those who analyze my writing say so—I do have it. That is, I can repeat a melody inwardly, but I cannot perform it aloud.

– How many songs have you written?

– About a hundred, perhaps. But only a few times did I write to existing music. In all other cases I simply allowed my poems to be set to song.

– And if we speak of the song as a genre, as a form of creativity?

– I love songs that resonate with my feelings. Russian songs especially—wedding songs, for instance. Even when you hear them in another language, you recognize them. They remain Russian nonetheless, just as the songs of other peoples remain theirs. Song is more immediately accessible than poetry. And in folk songs, I think, there are always elevated meanings.

– How important do you consider it to raise the question of the “cancellation” of Russian culture in our time?

– Culture cannot be canceled.

Perhaps this, too, is inherited through certain codes that have formed around Russia, a country that has always aroused keen interest—for its vast lands, the beauty of its places, the wealth of its resources. Russia has everything, but what is most important here is the human being. The meaning-shaping spheres have filled him, lifting his reason and feelings ever higher, step by step. That is why civilization must bear a human face.

– Tell us about the significant upcoming events where one may hear you, where readers may meet you and ask questions.

– I will be speaking on September 20 and 21 in Moscow at the World Public Assembly. The main theme of the gathering is public diplomacy. I am deeply convinced that the world is multipolar. The most crucial questions of this multipolar world are tied to humanitarian security. Our goal is the recognition of human capital as the highest value of the state—within the spheres of economics, politics, and sociocultural processes. About this, and much else, we will converse with more than two thousand guests.

The overarching idea of the Assembly is “a new world of conscious unity.” It is a landmark event for both Russia and the world, and I shall be glad to meet everyone there.

This interview was published in ng_exlibris on September 17, 2025