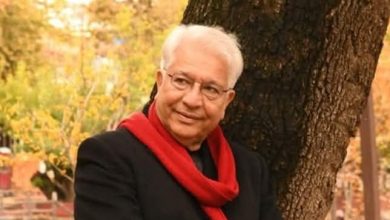

In September, Moscow hosted the Second International Congress of World Writers, gathering literary figures from 60 countries. Stan Center spoke with Ibrahim Istanbulli, a Syrian translator who for over twenty years has been introducing Russian literature and culture to the Arab world. The scholar shared his impressions of the congress and discussed the deep and growing interest in Russian literature among Arabic-speaking readers.

CIA and “A Good Man”

— Mr. Istanbulli, you recently attended the Second International Congress of World Organization of Writers in Moscow. What were your impressions of the forum and the city itself?

— Indeed, the World Organization of Writers, under the auspices of the World Public Assembly, held a two-day international congress in Moscow. Writers, translators, and thinkers from around the globe gathered—around a hundred participants from more than sixty countries.

Every continent was represented: from Latin America came delegates from Colombia, Brazil, Argentina, and Nicaragua. I personally spoke with Dr. Rubén Darío Flores Arcila, head of the Leo Tolstoy Institute of Russian Culture in Bogotá. He deeply loves Russia—its literature and culture. During our conversation, someone remarked that Rubén was “a good man.” I replied:

“Anyone who loves Russian literature and culture is, by definition, a good man.” Rubén laughed and added: “Only as long as he doesn’t work for the CIA!” Sadly, as he said, there are indeed people who fit that description.

There were also many writers from Africa—Morocco, Nigeria, South Africa, Sudan, Somalia, Egypt, Algeria, and Tunisia. Eurasia, too, was strongly represented: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and China. I was the only delegate from Syria, though I am proud to say I am also a citizen of Russia. From Europe, there were guests from Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, and Germany. One elderly German writer, who did not speak Russian but had a Russian wife, confessed passionately: “I am a Russophile!” He was deeply concerned about the future of relations between our two nations.

Naturally, many came from neighboring countries: Belarus, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Azerbaijan, and Abkhazia. The diversity of nations, peoples, and cultures was extraordinary—an inspiring sight indeed.

— A truly impressive gathering! Surely, many of the participants spoke the great Russian language?

— Unfortunately, not as many as one would hope. Those who hadn’t studied in the Soviet Union or Russia generally didn’t know the language. The ones who did—mainly from the former Soviet republics, or from countries like Romania and Poland—spoke it beautifully. Among our African and Latin American guests, only a few could converse in Russian, so we had to switch to English. It made discussion difficult, but their interest in Russia, its literature, and its culture was immense.

— And the European participants? Were they not afraid to travel to Russia, given how Western media fills libraries with “horror stories”?

— We all know how Russophobia is dressed up in the Western press, but I assure you, there was none of that spirit at the congress. The European writers who came to Moscow spoke joyfully and warmly. They expressed friendship, respect, and genuine affection for Russia and for Russian culture. I spoke at length with a Pole, a Romanian, and a German—all were outraged by the wave of Russophobia sweeping through Europe.

They came not out of fear, but out of conviction — and, above all, out of love for literature that unites where politics divides.

“Our Publishers Don’t Even Know Who Mandelstam Is”

— Mr. Ibrahim, at the congress you were awarded a medal “For the Excellent Translation of Russian Literature into Arabic.” Was it for a particular work, or in recognition of your entire career?

— It brought me great joy, honestly. To receive a medal at such a prestigious forum was deeply gratifying — I hadn’t expected it at all. I was told informally that I’d get some certificate, and suddenly — a gold medal!

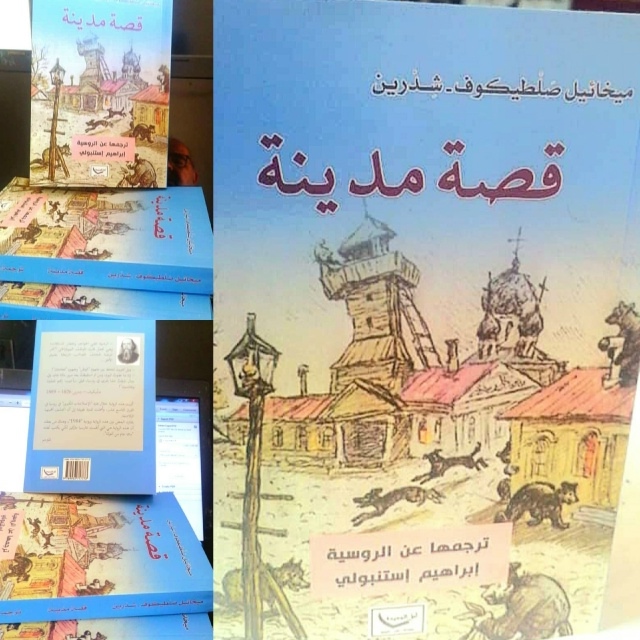

As the jury later explained, the award was for my entire body of work, not for one specific translation. They especially appreciated my renderings of the novels of Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, and the poetry of Sergei Yesenin, Marina Tsvetaeva, and Rasul Gamzatov. It was an honor given for the whole, and I am profoundly grateful for that.

— As far as I know, these works are only part of what you’ve translated. How many translations of Russian literature into Arabic have you completed, and which do you consider your best?

— Honestly, I can’t name an exact number, but about forty books of my translations have been published.

When I choose a work to translate, I don’t think about its market appeal. What matters to me is that it should benefit Arabic readers, offering them something of value. That’s why I translate not only fiction but also works in politics and economics.

Among my literary favorites are Tolstoy and the poets of the Silver Age. In political thought, I’d mention Alexander Dugin’s “Geopolitics of Postmodernity” — a truly fascinating study — and Valentin Katasonov’s “World Kabbalah”, a massive work. I’ve just completed a translation of another book by Katasonov, with his approval, which we hope will be published soon by Kalima Publishing in the UAE — one of the Arab world’s most prestigious publishing houses. They’ve already released one of my translations: Lev Shestov’s “Dostoevsky and Nietzsche” — a brilliant philosophical book.

Unfortunately, in the Arab world, neither Shestov nor his book is known; it’s nearly impossible to find. Yet, philosophically, it’s a masterpiece. Another work that means a lot to me is my book on Rasul Gamzatov, published in Syria two years ago for his centenary — 400 pages of poetry, prose, and testimonies from those who knew him closely.

I have many plans, but realizing them is often difficult. For six months now, I’ve been trying to publish my Arabic translation of Osip Mandelstam’s “The Noise of Time” — his only prose work. The problem is, our publishers don’t even know who Mandelstam is! They’re not interested. All that matters to them is profit — not whether the book or the translation is good. For me, it’s different. I want readers to know Mandelstam, Tsvetaeva, and others who have received little attention in the Arab world. I plan to continue translating, especially Yesenin and Shukshin. God willing, I will succeed.

— Arabic has many dialects. Are your translations accessible to all Arabic readers? For instance, would an Algerian, an Egyptian, and a Jordanian all understand them?

— Yes, Arabic has countless dialects. If I were to speak with someone from Morocco or Algeria in my own dialect, we wouldn’t understand each other at all — I can barely grasp the dialect of neighboring Iraq!

But literature is not about spoken language. Books are written in Modern Standard Arabic, which all educated Arabic speakers can read and understand — whether they are in Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia, or Iraq. Even Arabs living in Europe or the United States can read my translations, as long as they know literary Arabic.

As you know, not everyone who speaks Arabic is ethnically Arab: in Algeria and Morocco, many are not. In Syria, too, we have many ethnic groups — I myself am not Arab by origin. But all writers and translators work in Standard Arabic. There are occasional attempts, in Egypt or Iraq, to publish books in dialect, but that is, frankly, foolish and meaningless. No one outside those regions will understand them.

Sadly, some publishers don’t care — they think only of money. I wouldn’t even exclude that a few might have bad intentions, seeking to weaken the unity of the literary Arabic language, which has always been one of the strongest bonds of our cultural identity.

“In the Arab World, Russian Classics Are Deeply Loved”

— Is Russian classical literature still popular in Syria and, more broadly, in the Arab world?

— Always! My generation was raised on Russian classics — Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Chekhov, Turgenev, and Saltykov-Shchedrin. The latter is less known today, as he is more complex. Yet, new translations continue to appear because these names echo through generations.

The entire Arab world grew up reading the translations of my compatriot Sami al-Drubi, one of the great translators of the 20th century. Remarkably, he translated Tolstoy and Dostoevsky from French, not Russian! Though he didn’t know the Russian language, al-Drubi remains a phenomenon in the Arab translation tradition — respected, even revered. There is now a translation award named after him, and I was honored to receive it for my Arabic translation of Valentin Katasonov’s “World Kabbalah.”

Source: www.sweethoms.com

In short, the Arab world loves Russian classics profoundly. More than that — today there is a real boom in Russian literature. Many new translators from various Arab countries are emerging, though, admittedly, their competence often varies. Some are excellent, some average, and others poor — lacking proper training, never having studied or lived in Russia or the Soviet Union. Many, unfortunately, rely on artificial intelligence tools, which is far from ideal, but perhaps inevitable. There is no true mechanism to monitor translation quality — as they say, time itself will separate the gold from the sand.

— So, the poets of the Silver Age and modern Russian writers are less popular?

— I wouldn’t say that modestly. For nearly twenty years, I’ve been opening the Arab world to the poetry and literature of the Silver Age. I’ve long been in love with Yesenin, Tsvetaeva, Gumilyov, and Blok — magnificent poets. I regularly translate and publish their works on websites and social media.

In the past five years or so, readers have begun to pay real attention to this period. They are fascinated by it — they adore Tsvetaeva, and of course love Akhmatova as well. Personally, I feel closer to Tsvetaeva. To me, as a poet, she stands a step higher than Akhmatova.

— Based on your experience, how actively is Russian studied in Arab countries today, and are there enough opportunities for learners?

— Unfortunately, politics heavily influence this matter. When Syria maintained strong friendly relations with Russia, the Russian language was taught from the seventh grade onward. Both my son and daughter studied it, as did many other children. This continues for now, though I’m uncertain about the future.

I can’t speak for all countries, but wherever relations with Russia remain warm, the language is often part of the curriculum, or at least supported through institutes and cultural centers. Egypt, Morocco, and Algeria have excellent institutions for Russian studies; Iraq and Syria also belong to this group. How things will evolve, I don’t know — I can only hope for the best.

— In China, a million people study Russian, compared with over a hundred million studying English. What should be done globally so that more people learn Russian?

— Beyond maintaining good political relations, two things are essential: first, the promotion of the Russian language must not depend on political trends; and second, serious investment is required — in education, culture, and people devoted to sharing Russian language and literature with the world.

— In addition to good political relations between countries, two things are essential: first, that the promotion of the Russian language should not depend on political circumstances; and second, that there must be real investment in this field.

Frankly speaking, none of the officials — whether in Syria or elsewhere — show genuine interest in the state of the Russian language. They never have. Yet this is precisely the responsibility that should fall to cultural attachés, you see? It is necessary to find dedicated professionals in this field — people truly committed to the Russian language and literature, not bureaucrats wasting time on paperwork.

We must promote the Russian language with love! This mission should be entrusted to devoted people — those who feel a personal calling to it.

— Thank you for the conversation!

Ibrahim Istanbuli with Margarita Al, President of the World Organization of Writers (WOW), at the Second International Congress of World Writers in Moscow. (From the interviewee’s personal collection.)

English version for the Silk Road Today by: Ashraf Aboul-Yazid