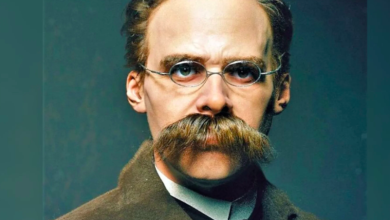

Emotional intelligence is a person’s ability to process emotional information that we receive (or convey) through emotions. Emotions carry information. The emergence and change of emotions follow logical patterns. Emotions influence our thinking and participate in the decision-making process. According to recent neurophysiological studies, it is impossible to make any decisions without emotions. The renowned neurophysiologist Antonio Damasio even wrote a book about this called Descartes’ Error.

The title of the book is related to Descartes’ famous phrase: ‘I think, therefore I am.’ From the point of view of modern science, a more accurate version would be: ‘I feel, therefore I am.’ Damasio argues that the final impulse in favour of one choice or another comes from the parts of the brain responsible for emotions. In 2002, psychologist Daniel Kahneman received the Nobel Prize in Economics for proving that economic decisions are influenced by irrational factors, including emotions.

The emotional competence model consists of four skills: the ability to recognise one’s own emotions; the ability to recognise the emotions of others; the ability to manage one’s own emotions; the ability to manage the emotions of others. When this model is presented in my training sessions and individual classes, participants often say: great, let’s start with the last skill! Many people are primarily interested in the skill of managing the emotions of others: it offers the most opportunities for leadership and more effective interaction with those around them.

At the same time, it is important to understand that this model is hierarchical — in other words, each subsequent skill can be developed once you have already mastered the previous one. In order to manage the emotions of others, you must first manage your own emotions. And in order to manage your emotions, you must first be aware of them. ‘We can only manage what we are aware of. What we are not aware of manages us.’ (Publius Syrus) Have we ever been taught to systematically become aware of our emotions? Even if parents or teachers sometimes draw children’s attention to this, it is very difficult to call this process systematic.

And what were we mainly taught to do with our emotions as children? Think back! What words were used? … ‘Hide,’ ‘suppress,’ ‘control’ — these are the ones we hear most often. This is the only way to manage our emotions that many of us have mastered to near perfection. At the same time, it is one of the most imperfect ways to manage them. Why? Firstly, this method is not selective. By suppressing our emotions, we suppress them all. It is impossible to suppress our anxieties and irritations every day and still retain the ability to feel joy. Second, let’s think about how we suppress our emotions. – With what tool? – With willpower! – everyone answers without thinking twice. – How? The next idea that usually comes to mind is: ‘With the brain.’ Hold any object with your ‘brain’ or ‘power of thought’. As a rule, no other ideas come to mind. — What do you hold a marker with? — That’s right, with your hand! And what is your hand attached to?

We use the same tool when we need to ‘hold’ our emotions. It is our body. Remember, when we hold back anger, our hands clenched into fists, our jaws clench too (no wonder there is an expression ‘to grind one’s teeth’). The clenching also happens internally: even our blood vessels constrict (hence the high incidence of cardiovascular disease among managers, who may have to restrain their emotions more often than others). And at the end of a difficult day, we may have a headache. So suppressing our emotions is harmful to our health. Thirdly, suppressed emotions do not go away.

As soon as the opportunity arises to vent these emotions, they burst out. Unfortunately, this opportunity most often arises at home, around our loved ones. Often, it is our loved ones who bear the brunt of all the irritation we have accumulated during the day. So suppressing emotions is harmful not only to ourselves, but also to our loved ones. Fourthly, suppressing emotions… impairs memory. Verbal information is particularly prone to being lost. There is even a theory that this is why men are worse at remembering and reproducing dialogue (since men suppress their emotions more).

I can anticipate your sceptical question: So, are you suggesting that we should let all our emotions out? Yes, some people do come to that conclusion. And here it is worth paying special attention to the following: the ability to control one’s emotions remains necessary in many cases. It is important to understand that it is not the only way; there are other ways to manage emotions that allow us to maintain our health and relationships with loved ones. In order to develop these skills, we must first realise what we are going to manage, because ‘restraint’ very often happens unconsciously; we have been taught since childhood to suppress our emotions and do so automatically. The ability to be aware of our emotions is the first thing we need to learn. Emotional competence begins with awareness of our own emotions.

People experience some kind of emotion at any given moment. However, it is very difficult to understand what we are feeling at any given moment — no one has ever helped us develop this ability. More often than not, we say what we think and cannot name a specific emotion, let alone identify its source. This is especially true when it comes to fleeting, weak emotions. It looks something like this: — What emotion are you feeling? — Well, I think I misunderstood something. ‘That’s what you think, but what do you feel?’ ‘Some kind of bewilderment, incomprehension…’ ‘Those are all mental processes. What do you feel?!’ ‘Yes, actually, it’s a trifle, there’s no reason to worry about it.’ ‘… ’Well… I guess I’m a little upset.”

A person with a high level of emotional competence is able to clearly recognise what emotion they are experiencing at any given moment, distinguish between degrees of emotional intensity, identify the source of the emotion, notice changes in their state, and predict how this emotion may affect their behaviour. Myths about emotional competence. Emotional competence = emotionality. A person with high (EI) is always calm and in a good mood. Emotional intelligence (EI) is more important than cognitive intelligence (IQ). How to measure emotional competence? There are currently no universally recognised tests for measuring emotional intelligence. I suggest assessing emotional competence through self-assessment of specific skills.

Emotional competence, like other skills, can be developed and practised. We have often been taught not to be aware of our emotions, but to suppress them. However, suppressing emotions is harmful to our health and relationships with others, so it makes sense to learn to be aware of our emotions and develop other ways of managing them. ‘How are you feeling?’ — awareness and understanding of your emotions. Assess how well you understand your emotions: Most often, the term awareness is used in psychotherapeutic texts to mean ‘the transfer into consciousness of certain facts that were previously unconscious.’ In order to be aware of our emotions, in addition to consciousness itself, we need words, a certain terminological apparatus. What is an ‘emotion’? Can emotions ‘not exist’? We divide emotions into “bad” and ‘good’ and hope to deal with them in this way. We encourage the good ones and suppress the bad ones. Strangely enough, many people think that this is enough.

The following definition is usually proposed:

Emotion is the body’s reaction to any change in the external environment.

The term ‘body’ is introduced in order to draw your attention to two conditional levels of our interaction with the world. We connect with it on the level of logic (as rational beings) and at the same time on the level of the organism (on a reflexive, instinctive and emotional level), without fully realising all the processes that are taking place. What kinds of emotions are there, i.e. how are they defined? ‘Anxiety’, ‘happiness’, “sadness”… and in order to remember them, some effort is required — they are not in our ‘working’ memory, we have to fish them out from somewhere deep inside. People struggle to remember what they are called! To make it easier to recognise emotions, it is worth introducing some kind of classification of emotional states.

Four classes of basic emotional states: fear, anger, sadness, joy. Fear and anger are emotions originally associated with survival. Sadness and joy are emotions associated with the satisfaction or dissatisfaction of our needs. Fear and anger are the most primitive emotions. If it can eat me, the fear response ensures that the body is restructured in order to escape. If it cannot eat me, a different kind of restructuring of the body is required, necessary for attack — the anger response.

So, from the point of view of the body’s main need — survival — fear and anger are very positive emotions. Without them, humans would not have survived at all, and the logical parts of the brain would certainly not have had enough time to develop and evolve. In the modern world, we are more interested in social interaction. And it turns out that people are wired in such a way that the emotional parts of the brain perceive threats to our ego and our social status in the same way as threats to the integrity of our body. Instead of positive and negative emotions, we prefer to use the terms ‘appropriate’ (to the situation) emotion or ‘inappropriate’ (to the situation) emotion. In this case, both the emotion itself and its intensity are important (‘it would be useful to worry a little about this, but panicking is completely unnecessary’).

Social stereotypes that interfere with emotional awareness. ‘Don’t be afraid of anything’… If we look at fear and courage from a logical point of view, a courageous person is someone who knows how to overcome their fear, not someone who does not experience it at all. ‘Don’t get angry’… This statement implies a ban on showing strong irritation and anger, or more precisely, on actions caused by anger that could harm those around you. The prohibition on actions is quite logical and necessary for modern society. But we automatically transfer this prohibition to the feelings themselves. Instead of acknowledging that we have emotions of the ‘anger’ class and managing them constructively, we prefer to think that we do not have these emotions. And then a grown woman suffers when she needs to be firm in her relationships with subordinates or negotiating partners, when she needs to stand her ground, defend her interests and those of her loved ones, and achieve her goals — because this requires the energy of anger and irritation.

Sadness and joy are emotions that are not observed in everyone, but only in those who have social needs. If we recall Maslow’s famous pyramid, we can say that the emotions of fear and anger are more closely related to the two lower levels of needs (physiological and safety needs), while sadness and joy are related to those needs that arise during social interaction with other people (needs for belonging and acceptance). In modern culture, sadness is generally not welcomed. People strive to avoid sadness and disappointment and live their lives so carefully… There is much that is good and valuable in a positive approach, but when understood correctly, it does not imply a ban on sadness.

What about joy?

Surprisingly, folk wisdom does not recommend that we rejoice either: ‘laughter without reason is a sign of foolishness.’ Many cultures revere suffering, tragedy, or self-sacrifice for the sake of someone (or rather, something). By the way, what emotion do you think is most commonly expressed at work? And the least commonly expressed? The most commonly expressed emotion at work is anger, and the least commonly expressed is joy. This is most likely due to the fact that anger is associated with power, control and confidence, while joy is associated with frivolity and carelessness (‘we are here to work, not to giggle’). Emotions and the brain. The neurophysiological basis of emotional intelligence.

The neocortex, or “new cortex”, is the most recently evolved part of the brain and is most developed in humans. The neocortex is responsible for higher nervous functions, in particular thinking and speech. The limbic system is responsible for metabolism, heart rate and blood pressure, hormones, smell, feelings of hunger, thirst and sexual desire, and is also strongly linked to memory. The limbic system, by adding emotional colour to our experiences, contributes to learning: behaviours that are ‘pleasant’ will be reinforced, while those that lead to ‘punishment’ will gradually be rejected. If, when we say ‘brain,’ we usually mean the neocortex, then when we say ‘heart,’ oddly enough, we also mean the brain, namely the limbic system.

The oldest part of the brain — the reptilian brain — controls breathing, blood circulation, and the movement of the body’s muscles, and ensures the coordination of hand movements when walking and gesturing during verbal communication. This brain functions during a coma. The memory of the reptilian brain functions separately from the memory of the limbic system and the neocortex, that is, separately from consciousness. Thus, it is in the reptilian brain that our ‘unconscious’ is located. The reptilian brain is responsible for our survival and deepest instincts: obtaining food, seeking shelter, defending our territory (and mothers protecting their young). When we sense danger, this brain triggers a ‘fight or flight’ response.

When the reptilian brain is dominant, a person loses the ability to think at the level of the neocortex and begins to act automatically, without conscious control. When does this happen? Primarily in cases of immediate danger to life. Since the reptilian complex is more ancient, significantly faster, and capable of processing much more information than the neocortex, wise nature has entrusted it with making decisions in dangerous situations. It is the reptilian complex that sometimes helps us ‘miraculously survive’ in critical situations.

As long as the intensity of emotional signals is not very high, the parts of the brain interact normally and the brain as a whole functions effectively. But when the intensity of emotional signals exceeds a certain level, our logical thinking declines sharply. The global drama of emotional intelligence. For emotions of high intensity (about which we know a lot and for which we have many words to describe them), we do not have a directly conscious tool — the brain (or rather, it works very poorly). And for emotions of low intensity, when this tool works perfectly, there are no words — no other tool of awareness.

There is a very narrow area somewhere in the middle where we can be aware of emotions, but here we lack the skill and habit of systematically paying attention to our emotional state. Precisely because we do not know how to be aware of emotions, we do not know how to control them. ‘It is precisely those passions whose nature we misunderstand that have the strongest hold on us. The weakest are those whose origin we understand.’ (Oscar Wilde) Emotions and the body. Awareness of emotions through bodily sensations and self-observation. What does it mean to pay attention to your emotional state?

Emotions live in our bodies. Thanks to the limbic system, the emergence and change of emotional states almost immediately causes some changes in the state of the body, in bodily sensations. Therefore, the process of awareness of emotions is, in essence, the process of matching bodily sensations with a word from our vocabulary or a set of such words. There is a theory that people are divided into kinesthetics (people who best perceive, remember and process information through sensations, movements, touch, smells and tastes, as well as through practical experience), visuals (people who perceive and remember most information through sight (images, pictures, diagrams, colours), use ‘visual’ words in communication (‘look,’ ‘saw,’ ‘bright’), appreciate beauty and order, and pay attention to appearance, which is part of their style of perceiving the world) and auditory learners (people who perceive and process information primarily through hearing, remembering better by ear, preferring audio formats (lectures, podcasts, phone calls), paying attention to voice and intonation, and often being irritated by noise) based on their way of interacting with the world around them.

Kinesthetics are more familiar and understandable to sensations, visuals to visual images, and audibles to sounds. Try to imagine yourself as an outside observer, then you may notice that you are slightly pushing your head into your shoulders (fear), or constantly pointing your finger, or speaking in a higher voice, or your intonation is slightly ironic. To be aware of our emotions, we need consciousness, terminology, and the ability to pay attention to ourselves, and for that we need training. Awareness and understanding of emotions. When we talk about understanding, we mean several factors. First, it is understanding the cause-and-effect relationships between specific situations and emotions, that is, answering the questions ‘What causes different emotional states?’ and ‘What consequences can these states have?’ Second, it is understanding the meaning of emotions — what does a particular emotion signal to us, why do we need it? Emotional ‘cocktails’. The proposed model is also helpful in developing the skill of awareness, because with its help, any complex emotional terms can be ‘broken down’ into a spectrum of four basic emotions and something else. How do we ‘protect’ ourselves from fears? Everything that is unknown and new to us must first be scanned for danger at the organism level. At the level of logic, we may be ready for change and even sincerely ‘wait for change.’

But our organism resists it with all its might. Social fears. The threat of losing social status, respect and acceptance by others is just as significant to us, because it means being left alone. There are far more unconscious fears (deeply hidden, often irrational fears that influence behaviour and decisions without the person being aware of them) in our lives than we are used to thinking. Is it possible to be angry with oneself? Let’s introduce a metaphor — the direction of an emotion, or rather not even an emotion, but possible actions that may follow this emotion. Fear makes us run away from the object or freeze. That is, fear is directed ‘away’ from something. Sadness is directed inward, it focuses us on ourselves. But anger always has a specific external object; it is directed ‘towards.’ Why? Because that is the very essence of the emotion — anger primarily incites us to fight. And no normal ‘organism’ will fight with itself, it is contrary to nature.

But we were taught as children that it is not good to get angry, so the idea arises: ‘I am angry with myself.’ Emotions and motivation. So, emotion is first and foremost a reaction; we receive a signal from the outside world and react to it. We react by directly experiencing this state and taking action. One of the most important purposes of emotion is to motivate us to take some kind of action. Emotion and motivation are words with the same root. They come from the same Latin word movere (‘to move,’ ‘to set in motion’). The emotions of fear and anger are often referred to as the ‘fight or flight’ response. Fear motivates organisms to engage in defensive behaviour, while anger motivates them to attack. When it comes to humans and their social interactions, we can say that fear motivates us to preserve and protect something, while anger motivates us to achieve something. Decision-making… Emotions and intuition. Before making a decision, people usually consider various options, think them over, discard the most unsuitable ones, and then choose from the remaining options (usually two). They decide which one is preferable — ‘A’ or ‘B’.

Finally, at some point, they say ‘A’ or ‘B.’ And what that final choice will be is determined by emotions. The mutual influence of emotions and logic. Not only do our emotions influence our logic, but our rational thinking also influences our emotions. Thus, the expanded definition would be as follows: Emotion is the reaction of the body (the emotional parts of the brain) to changes in the environment external to these parts. This can be a change in the external world or changes in our thoughts or in our body. Awareness and understanding of others’ emotions. ‘People’s feelings are much more interesting than their thoughts.’ (Oscar Wilde) Assess how well you understand the emotions of others: Essentially, the process of recognising the emotions of others means that at the right moment, you should pay attention to what emotions your interaction partner is experiencing and name them. In addition, the skill of understanding the emotions of others includes the ability to predict how your words or actions may affect the emotional state of another person.

It is important to remember that people communicate on two levels: on the level of logic and on the level of the ‘organism.’ It can be difficult to understand the emotional state of another person because we are accustomed to paying attention to the logical level of interaction: numbers, facts, data, words. The paradox of human communication: on the level of logic, we are not very good at recognising and understanding what another person is feeling, and we think that we can hide and conceal our own state from others. However, in reality, our ‘organisms’ communicate perfectly well with each other and understand each other very well, no matter what we may imagine about our self-control and ability to keep ourselves in check!

So, our emotions are transmitted and read by other ‘organisms,’ regardless of whether we are aware of them or not. Why does this happen? To understand this, you need to know that there are closed and open systems in the human body. The state of one person’s closed system does not affect the state of the same system in another person. Closed systems include, for example, the digestive or circulatory systems. The emotional system is an open one: this means that the emotional background of one person directly affects the emotions of another. It is impossible to make an open system closed. In other words, no matter how much we sometimes want to, we cannot forbid our ‘organisms’ from communicating.

The influence of logic and words on the emotional state of the interlocutor. We usually tend to judge the intentions of others by their actions, based on our own emotional state. One of the most important components of the skill of recognising the emotions of others is understanding the emotional effect our actions will have. It is important to take responsibility for your actions and remember that people react to your behaviour, not your good intentions. Moreover, they are under no obligation to guess your intentions and take them into account if your behaviour causes them unpleasant emotions.

It is worth remembering two simple rules. If you are the initiator of communication and want to achieve your goals, remember that it is not your intentions that matter to the other person, but your actions! If you want to understand another person, it is important to be aware not only of their actions, but also, if possible, of the intentions that dictated them. Most likely, their intention was positive and kind, but they simply could not find the right actions to match it. To understand the emotions of others, we must take into account that the emotional state of another person affects our own emotional state. This means that we can understand others by being aware of changes in our own emotional state — we can feel what they are feeling — this is called empathy.

The emotional state of another person manifests itself at the ‘organism’ level, that is, through non-verbal signals — we can consciously observe the non-verbal level of communication. We are well aware of and understand the verbal level of interaction — that is, to understand what the other person is feeling, we can ask them about it. So, we have three main methods of recognising the emotions of others: empathy, observation of non-verbal signals, and verbal communication: questions and assumptions about the feelings of others. Empathy. Recent discoveries in neurophysiology confirm that the ability to unconsciously ‘mirror’ the emotions and behaviour of others is innate. Moreover, this understanding (‘mirroring’) occurs automatically, without conscious thought or analysis. If all people have mirror neurons, why are some people so good at understanding the emotions of others, while others find it so difficult?

The difference lies in the awareness of one’s own emotions. People who are good at picking up on changes in their own emotional state are intuitively very good at understanding the emotions of others. People who are less capable of empathy find it more difficult to establish contact with others and understand their feelings and desires. Many of them easily find themselves in situations involving interpersonal misunderstandings and miscommunication. Why do we feel what others feel? The significance of mirror neurons. For a long time, the nature of this phenomenon remained unknown. It was only in the mid-1990s that Italian neurologist Giacomo Rizzolatti (born 28 April 1937, Kyiv), discovered the so-called mirror neurons and was able to explain the mechanism of the ‘reflection’ process. Mirror neurons help us understand others not through rational analysis, but through our own feelings, which arise as a result of internal modelling of another person’s actions. We cannot refuse to ‘mirror’ another person.

Moreover, our internal copy of another person’s actions is complex, that is, it includes not only the actions themselves, but also the feelings associated with them, as well as the emotional state accompanying the action. This is the basis of the mechanism of empathy and ‘feeling’ another person. If you want to learn something, watch people who are good at it. ‘Fool me.’ Understanding non-verbal behaviour. ‘The joy of seeing and understanding is the most beautiful gift of nature.’ (Albert Einstein) Let’s figure out what non-verbal behaviour is. Very often, it is understood as ‘body language’. At one time, many books with similar titles were published, the most popular of which was probably Allan Pease’s ‘The Body Language of the Mind’.

What do we actually mean by verbal communication? These are the words and texts that we communicate to each other. Everything else is non-verbal communication. In addition to gestures, our facial expressions, postures and the position we occupy in space (distance) relative to other people and objects are also very important. Even the way we dress conveys non-verbal information (arriving in an expensive suit and tie or in ripped jeans). There is another component of non-verbal communication. The texts we communicate are spoken with a certain intonation, speed, and volume; sometimes we articulate all the sounds clearly, and sometimes, on the contrary, we stumble and make reservations. This type of non-verbal communication has a separate name — paralinguistic (characteristics of non-verbal means accompanying speech (intonation, volume, timbre, pauses, tempo) that are not part of the language itself, but carry additional semantic and emotional information, reinforcing or modifying the verbal message) . There is a so-called Mehrabian effect (the 7-38-55 rule), which states that when meeting someone for the first time, a person trusts only 7% of what the other person says (verbal communication), 38% of how they say it (paralinguistic), and 55% of how they look and where they are located (non-verbal). Why do you think this is the case? Emotions reside in the body, and therefore, they manifest themselves in the body, no matter how much one tries to hide them. Therefore, if a person is insincere, their emotions will betray them, regardless of what they say.

There are two opposing points of view. The first says that people are inherently evil, selfish, and ready to defend their interests, not shying away from anything, including deception. The second says that people are inherently inclined to do good. Each of us has met people who would confirm the validity of both points of view. However, whichever point of view you believe in, you will attract people who share it and (unconsciously) find yourself in situations that confirm it. Therefore, let’s not talk about conscious deception, but use the emotionally neutral term ‘incongruence’. This term is used when talking about the inconsistency of verbal and non-verbal signals. What should you do to learn to understand non-verbal behaviour?

Don’t delude yourself into thinking that you will then be able to ‘read’ other people, as promised in the headlines of fashion magazines. It is worth understanding non-verbal communication as a whole and paying attention to its various aspects. The most important factor for interacting with and understanding another person is a change in their non-verbal position. If you notice this change, you can ask them a question, and then you will be able to get more information from them. Just as with recognising your own emotions, practice is important. Turn on the TV and mute the sound.

Find a movie and watch it for a while, observing the gestures, facial expressions, and positioning of the characters. Public transport. How do people feel on public transport? If you see a couple, what is their relationship like? If someone is telling someone else a story, is it a funny story or a sad one? Conference. Are these two people genuinely happy to see each other, or are they just pretending to be happy when in fact they are competitors who dislike each other? Office. ‘What is this person feeling right now?’ ‘What emotions are they experiencing?’ Having come up with some answers, we can then analyse what we observe in this person’s non-verbal behaviour and ask ourselves whether our assumptions about this person’s emotions correspond to our ideas about gestures, postures and facial expressions.

Observing paralinguistic communication. If a person suddenly starts stuttering, stammering, mumbling or talking incessantly, this is most likely an indication of some degree of fear. Aggressive emotions can be characterised by an increase in the volume of speech. When feeling melancholy or sad, people tend to speak more quietly, slowly and mournfully, often accompanying their speech with sighs and long pauses. Joy is usually shared in higher tones and at a faster pace (remember how the crow in Krylov’s fable ‘was so overcome with joy that it could not breathe’), so the tone becomes higher and the speech more incoherent. However, this mainly applies to strongly expressed emotions. Therefore, to improve your skills in understanding paralinguistic communication, we can again recommend that you include an observer of this process more often.

‘Would you like to talk about it?’ How to ask about feelings? A direct question can cause some anxiety or irritation, or both. It turns out that it is not so simple to understand and comprehend the emotions of others through direct ‘questioning.’ The main difficulties of the verbal method of understanding the emotions of others are that people do not know how to understand their emotions, and it is difficult for them to answer questions about feelings and emotions correctly. The question itself, due to its unfamiliarity, causes feelings of anxiety and irritation, which reduces the truthfulness of the answer. Open-ended questions, as the name suggests, ‘open up’ space for a detailed answer, for example: ‘What do you think about this?’ Closed questions ‘close’ this space, assuming an unambiguous answer. ‘Yes’ or ‘no’. In communication theory, it is recommended to refrain from asking too many closed questions and to use open questions more often. Since it is not very common in our society to ask about emotions, it is important to phrase these questions very gently and apologetically. So, from the phrase: ‘Are you mad right now?’ — we can use: ‘May I suggest that you are perhaps a little annoyed by this situation?’ Use the following speech formula, which has been verified by the authors and is the most correct. Any technique = essence (core of the technique) + ‘amortisation’. The essence is the logical level of application of the technique, and the cushioning is the emotional level. Empathetic statement. In communication theory, there is a concept called an empathetic statement, which is a statement about the feelings (emotions) of the interlocutor. The structure of an empathic statement allows the speaker to express how they understand the feelings experienced by another person without evaluating the emotional state being experienced (encouragement, condemnation, demands, advice, downplaying the significance of the problem, etc.).

It is enough to say to an irritated person: ‘It must be annoying when there are constant delays in the project,’ and they will become noticeably calmer. Why does this work? Most people are not aware of their emotions, just like this person. But the moment they hear a phrase about emotions, they involuntarily pay attention to their emotional state. As soon as he becomes aware of his irritation, his connection with logic is restored and his level of irritation automatically drops. What happens if we are not aware of (do not understand) other people’s emotions? ‘Learn to control yourself’ — Managing your emotions. Assess how well you manage your emotions: General principles of emotion management: The principle of responsibility for your emotions. I am solely responsible for what I feel at a given moment in time.

How can that be, when we cannot influence what another person says to us? Indeed, we cannot always change the situation itself. However, we are now talking about our emotional state — and that is precisely what we can control. To recognise that I am capable of controlling my own state is to take responsibility for my emotions and the actions that follow from those emotions. The principle of accepting all your emotions. All emotions are useful in one situation or another, and therefore it is illogical to permanently exclude any emotion from one’s behaviour. Until we acknowledge the presence of an emotion, ‘see it’, we cannot see the situation as a whole, that is, we do not have enough information. And naturally, by not acknowledging the presence of an emotion, we cannot part with it, and it remains somewhere inside us in the form of muscle tension, psychological trauma, and other unpleasantness.

If we forbid ourselves to experience an emotion that we consider negative, our emotional state deteriorates even further! Similarly, if we forbid ourselves to feel sincere joy, then joy disappears. By losing part of our emotions, we also lose the feeling of fulfilment in life. There is another way. Bring emotions back into your life. Bringing them back does not mean becoming emotionally unrestrained. It means accepting the right of emotions to exist and finding additional ways to manage them. Let’s start the return with ‘small’ joys. The view of the uninitiated. To explain the essence of this method, we need to describe the city in which we live. This is called ‘the view of the uninitiated’ — the view of a person who sees something for the first time. As we know, ‘you quickly get used to good things.’ And we get used to the city we live in, the company we work for, the people around us. When choosing any behaviour, the key is to answer the question: ‘What is the goal?’ In addition to the goal, there are two other important characteristics of an action: price and value. Value is the benefits I will receive by taking action; The cost is what I will have to pay to obtain these benefits. Only sophisticated manipulators can ensure that they receive only value and pay no cost. The most effective actions in managing emotions are those that help achieve the desired result (value) at the lowest cost (price).

Algorithm for managing emotions. Managing emotions can be divided into two subgroups: reducing the intensity of a ‘negative’ emotion and/or switching it to another (‘negative’ emotion in our meaning is one that prevents us from acting effectively in a given situation). Evoking emotions in yourself (identify your strengths (creativity, curiosity, honesty, kindness) and deliberately apply them; use positive affirmations to create the right mood; to reduce the intensity of negative emotions, consciously evoke feelings that will help you act effectively; focus on happiness, gratitude, curiosity, and pleasure).

The quadrant of managing your emotions: In addition, we can consider reactive and proactive emotion management. Reactive emotion management is necessary when emotions have already arisen and are preventing us from acting effectively. These methods are also called “online” methods, because something needs to be done right now, at this very moment. Proactive emotion management refers to managing your emotional state outside of a specific situation (‘offline’) and may include analysing the situation (why do I get so worked up? What can I do differently next time?), working on creating a general mood and background mood. Emotion management techniques can be placed in our quadrant: Emotion management techniques can also be divided into physical and mental. Physical techniques are related to managing emotions at the muscular level (since, as we remember, emotions live in the body); Mental techniques are related to managing emotions by changing our thoughts. Breathing is the most effective technique for managing emotions. Verbalising feelings is also a good old method, more often referred to by the simpler word ‘talking it out’.

If you don’t bottle up your emotions, it only takes a few sentences and a couple of minutes to share them. Communicating your emotions is not a loss of power, it is a different kind of power. We mainly communicate our emotions to others through so-called ‘YOU messages’: ‘You annoy me!’; ‘Don’t intimidate me!’ ‘YOU messages’ cause irritation and discontent. This person does not annoy you; they are solving their own problems. At the same time, you experience certain emotions.

This is what you should communicate: ‘I’m starting to get angry’; ‘I’m a little worried.’ This is a form of ‘I message.’ Words and speech are our way of expressing ourselves in this world. As long as we are thinking about something, the world has no way of knowing about it. Only by telling another person or writing down our ideas can we share them with the world. In addition, when we express our thoughts to another person, we want to be understood, which means we structure our thoughts in some way.

Therefore, sometimes, when telling someone else about something, we suddenly realise something important about the situation that we had not noticed before. Thanks to this, verbalisation can also be a way of becoming aware of our emotions. If you find it difficult to start talking about your emotions, then at least start writing about them. When people write down what they are going through, their blood pressure and heart rate decrease, and their immune system improves. ‘Meta-position’ is the ability to look at yourself, your thoughts, feelings, and situations from the outside, as if from the perspective of an impartial observer, without merging with your emotions or identifying with them. this is a skill of awareness that allows one to ‘step out’ of the role of a participant and become a ‘spectator,’ which helps to reduce emotional reactivity, understand oneself more deeply, and find non-standard solutions to problems).

In this way, we seem to ‘step out of the situation,’ leaving all our emotions inside it, and have the opportunity to look at what is happening objectively. As we know, strong emotions prevent us from thinking. What is less well known is that the opposite is also true: active thinking reduces the intensity of the emotions we experience. In situations where we are excited or very nervous before an event, it is helpful to start thinking. The ability to cope with momentary impulses is one of the components of the skill of managing one’s emotions. Marin